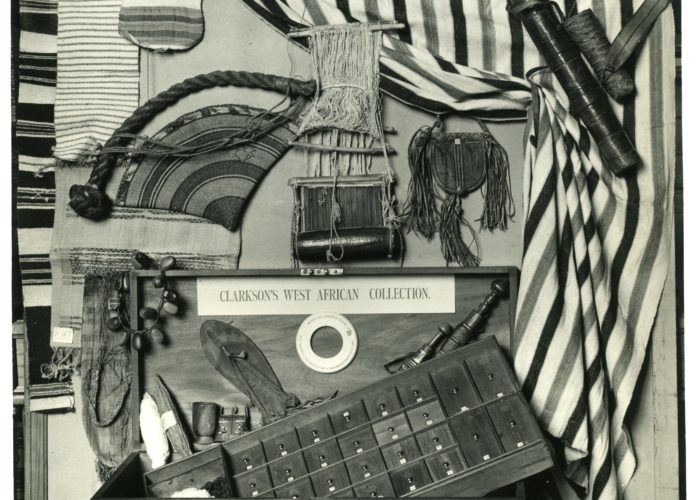

Thomas Clarkson’s campaign chest

Theme: Social and cultural revolution, Challenging slavery: abolition and opposition, Trade, tariffs and taxes, People in motion: exiles and opportunities

Between the 1500s and early 1800s, millions of Africans were kidnapped, sold and transported to the Americas to work as slaves, in unimaginably cruel conditions, on hugely profitable plantations, producing sugar, tobacco and other commodities. These plantations were largely owned by Europeans and Euro-Americans. Britain grew rich on the profits from this transatlantic slave trade, which were reinvested into other economic sectors. Only in the late eighteenth century did public opinion slowly begin to turn against the trade in Africans, and campaigners for abolition used every way they could to bring the issue to people’s attention in Europe.

Thomas Clarkson (1760 – 1846) was a significant figure in the formation of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Although he trained for a career in the Church, he devoted his life to telling people about the horrific nature of transatlantic slavery and campaigning for its abolition. He travelled across Britain, particularly to ports such as Bristol and Liverpool, which imported and processed many of the goods produced on plantations in the Americas, giving talks and collecting evidence for the society to present to the public, and to lobby politicians such as William Wilberforce.

Clarkson recognised that most people living in Britain at the time had never encountered people of African origin, and that slavery was a ‘faraway evil’ of which they saw nothing. He realised that, when trying to help people understand the horrors of slavery, showing them pictures and artefacts would influence them far more than words alone. He collected tools, clothing and crafts made by Africans in their homelands to show the sophistication of the peoples who had been enslaved. He also produced examples of iron shackles, leg irons and thumb screws used on African men, women and children as they were kidnapped, sold and transported to the Caribbean and the Americas. He created a special travelling box – a‘campaign chest’ – in which to carry these items.

Clarkson also realised the importance of appealing to different sectors of society – helped by his collaboration with nonconformist groups such as Quakers and evangelicals. Drawing on some of the techniques developed by reformers and revolutionaries, he urged women and ordinary working people (who did not have the vote at that time) to wear badges supporting the abolition campaign and to boycott sugar produced in the Caribbean. He gave talks, wrote letters to the papers and collected signatures for anti-slavery petitions.

Clarkson talked about the cruelty experienced by enslaved Africans and their attempts to resist their enslavement. He used personal testimonies, such as Olaudah Equiano’s extraordinary autobiography about his experiences of enslavement, as powerful illustrations of slavery, and talked about the great number of seamen who died on slaving voyages. Some of the best evidence and supportive examples Clarkson found came from former slaves who had fled to, or fought for, the British army during the American War of Independence, many ending up in and around London in the 1780s.

The British trade in people was outlawed by the government in 1807 and British slavery finally abolished in 1833.

Did you know..?

To gather evidence against the slave trade, Clarkson travelled over 35,000 miles and interviewed 20,000 sailors.

Use our Classroom resources to investigate this object and the theme of Abolition further.

Highlights:

- Using objects, artworks and other sources to find out about the past

- Enquiry: Who fought for the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade and what were some of the tactics they used?

And much more…

Sources & acknowledgements

This object description and its related educational resources were researched and written by our team of historians and education specialists. For further information see the item’s home museum, gallery or archive, listed above.

-

Did you know..?

To gather evidence against the slave trade, Clarkson travelled over 35,000 miles andinterviewed 20,000 sailors.

-

Education overview

You can access a range of teachers resources related to this object and more on our education page.

Please also see our glossary of terms for more detailed explanations of the terms used.

-

Curatorial info

- Originating Museum: Wisbech and Fenland Museum

- Production Date: c.1785

- Material: Wood

- Size: H: 28cm W: 66cm D: 36cm

- Original record

-

Use this image

You can download this image for personal and educational use but please take note of the license type and rights holder information.

- Rights Holder: Wisbech and Fenland Museum

- License Type: