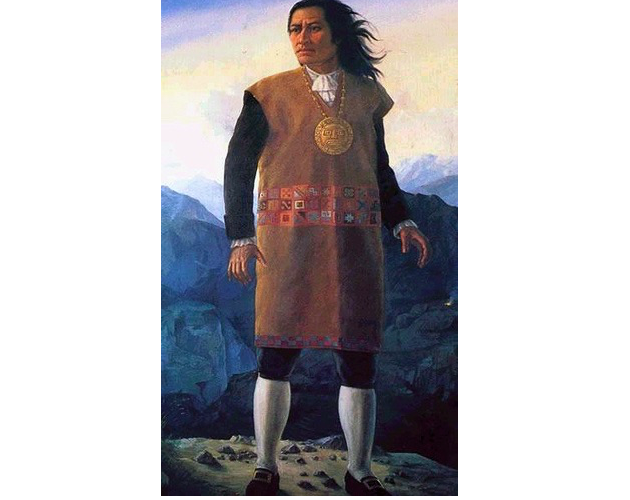

Túpac Amaru II

Theme: War and the international order, Spanish American wars of independence (1808-1833)

Túpac Amaru II was the leader of the largest uprising in colonial Spanish-American history which raged across the Andes from 1780-1783. It became more violent as it progressed, and also more radical, more antislavery, and more anti-Hispanic. Its leader is still remembered in Peru and Bolivia and beyond today.

Túpac Amaru II (1738 – 1781) was born Jose Gabriel Condorcanqui in the Tinta region of Peru. At that time, a large part of South America was ruled by Spain, and the population was a mixture of Spanish, Native Americans, and people of African origin (many of them enslaved). As a young man, Condorcanqui inherited his father’s role as cacique (leader of the local indigenous peoples). He repeatedly appealed to the Spanish governors to reduce the heavy taxes and improve working conditions (including forced labour) for the local people.

When his appeals were ignored, Condorcanqui eventually arrested the Corregidor (a local Spanish official) Antonio de Arriaga and had him hanged in front of a large crowd. Condorcanqui renamed himself Túpac Amaru II, after his ancestor who was the last indigenous ruler of the Incas, and launched an uprising in favour of freedom for indigenous and enslaved peoples.

The rebellion, initially led by Túpac Amaru along with his wife Micaela Bastidas, raged between 1780 – 1783. Túpac asserted the rebellion was the result of ‘repeated outcries’ from the indigenous peoples against the abuses committed by European-born Crown officials. Around 6,000 Native Americans assembled and began to march in rebellion.

Túpac successfully captured the town of Sangarara in November 1780, but the actions of the rebels in attacking Spaniards’ houses and their violence meant that there was no support amongst the ruling classes and the initial victory was followed by a string of defeats and retreats. Bastidas commanded her own battalion of insurgents and for a time Túpac managed to create an alliance between Quechua speakers and rebels from Bolivia. The alliance collapsed, however, and in 1781, Túpac and Bastidas were betrayed to the Spanish authorities in Cuzco. They were arrested, along with their family and sentenced to death.

Accounts of the exact events differ, but it is clear that Túpac’s execution was particularly barbaric – reflecting the fear the insurrection caused to colonial powers. He was forced to witness the execution of a number of his family including his wife and one of their sons. His tongue was cut out and his arms and legs tied to four horses which all pulled in opposite directions. When this failed to separate his limbs from his body, he was beheaded. The couple’s youngest son was forced to witness this before being sent to Spain and imprisoned. The heads and limbs of the dead were displayed in various places as a warning to others. However, despite this gruesome display, the rebellion continued for another two years, led by Túpac’s relatives, including another son.

Although ultimately unsuccessful, the uprising helped to inspire a wave of rebellions against colonial rule. Túpac and Bastidas became heroes of Andean peoples and indigenous rights, and Peru eventually gained its independence in 1811.

Did you know..?

According to some sources, of the 73 leaders of the rebellion who were captured, 32 were women.

Use our Education activities to investigate this object and the theme of further.

Highlights:

And much more…

Sources & acknowledgements

This object description and its related educational resources were researched and written by our team of historians and education specialists. For further information see the item’s home museum, gallery or archive, listed above.

- Related resources

-

Did you know..?

According to some sources, of the 73 leaders of the rebellion who were captured, 32 were women.

-

Education overview

You can access a range of teachers resources related to this object and more on our education page.

Please also see our glossary of terms for more detailed explanations of the terms used.

-

Use this image

You can download this image for personal and educational use but please take note of the license type and rights holder information.

- License Type:

Public Domain

- License Type: