Surgeon George James Guthrie, Wellington’s combat medic

George James Guthrie, the supreme military surgeon

In 1794, a distinguished Scots surgeon, John Bell pleaded for reform, “The situation of a military surgeon is more important than of any other. While yet a young man he has the safety of thousands committed to him in the most perilous situations, in unhealthy climates, and in the midst of danger. He is to act alone and unassisted, in cases where decision and perfect knowledge are required; in wounds of the most desperate nature, more various than can be imagined, and to which all parts of the body are equally exposed; his duties, difficult at all times, are often to be performed amidst the hurry, confusion, cries and horror of battle”.

Despite the hundreds of thousands of deaths and injuries suffered in the 23-year Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, little attention is given to the massive amount of suffering and the efforts of around 1200 and 1400 surgeons in the British Army and Royal Navy respectively.

Whilst we read much of Dominic Jean Larrey and François Percy, French surgeons of the Grande Armée, who had practiced their craft over the battlefields of Europe for 22 years, less is known of British surgeons who supported Wellington in his campaigns. George James Guthrie was one of these. He was born in London on 1st May 1785. His great grandfather was a Scot and fought at the Battle of the Boyne. His Irish father took over a successful business from a surgeon, Guthrie’s uncle, who produced therapeutic medical plasters (Emplastrum Lythargyri – lead pla(i)sters for topical sedative and astringent application) and other surgical supplies for the forces. Unfortunately, Guthrie’s wealthy father alienated himself from the family and Guthrie had to rely on his own talents to build his career.

George James Guthrie.

(Oil painting by Henry Room – courtesy of the Royal College of Surgeons of England)

His family were wealthy enough to educate young George at a private school, where he met a French Abbé, Monsieur Noel an émigré, who taught him French, which was to prove of immense value in his work. Noel also taught him dead reckoning and this helped Guthrie save a ship from foundering near the Isle of Wight. George Guthrie had a severe accident the age of thirteen. A surgeon named Mr John Rush cared for him. Rush was Inspector General of Army Hospitals. He thought Guthrie a likely lad and proposed to Guthrie’s father that the boy should become a military doctor. This was agreed and Guthrie was apprenticed (at 13 years) to a Mr Phillips – a surgeon of Pall Mall and to Dr Hooper of the Marylebone Dispensary/Infirmary.

The training of surgeons in the pre-anaesthetic days of the early 19th century was rather haphazard. Apprenticeship followed primary schooling at the early age of fifteen. After 5 years, this indentured contract, struck between master and pupil, ended and the trainee went to a provincial or metropolitan hospital to walk the wards and attend lectures. Subsequent success in gaining a diploma or, rarely a doctorate, gave license to practise.

As an apprentice, Guthrie was taught the rudiments of diagnosis, prescribing and minor surgery – eg bleeding, draining abscesses and dressing patients’ wounds. Guthrie formed a particular attachment to Hooper, a diabetic who, when later faced with a fatal bladder infection, said to Guthrie, “Mind, George, if I am to be cut – you must do it” – an early forecast of the young surgeon’s operative skills. Guthrie attended a series of lectures at the renowned Windmill School of anatomy, in Soho.

Windmill School of anatomy. Dissection, a critical learning process for army surgeons.

(Courtesy Royal College of Surgeons of England)

In June 1800, many of the sick and wounded evacuated from the abortive expedition to the Helder were collected in the York military hospital, Chelsea (built on the site of the “Star and Garter Inn” – near one end of Eaton Square). Guthrie was appointed a surgical mate to help with the cases. He acted as a dresser (and deputy grinder – of students!) to a Mr Carpue and to Mr Keate (Surgeon General to the Army). A problem arose in that the latter had recently issued an order that no hospital mate (later called Hospital Assistant) could be employed without passing an examination at the new Royal College of Surgeons of London.

In 1800, Guthrie was only 15 – the age at which many men entered apprenticeship. Although it would be illegal to sit the exam at this age from 1802 onwards, having been quizzed by Keate and a Mr Howard, he passed. He was the youngest surgeon ever to take the examination, which made him a member of the College.

Guthrie’s first military appointment was as assistant surgeon to the 29th Foot.

Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Montagu sent Guthrie off to Lieutenant Colonel Byng (later Lord Strafford), who commanded the regiment at Winchester. The 29th were posted to North America in 1802, where Guthrie served for five years. He married a surgeon’s widow – the daughter of Walter Patterson, Lieutenant Governor of Prince Edward Island – in 1804, at Halifax, Nova Scotia. During this tour, he was promoted to full surgeon of the regiment. It was then said that, “no regiment was ever better commanded or better doctored”.

Embarking for home in 1807, the regiment went to Cadiz and Gibraltar under the command of General Spencer. Guthrie, having acquired a useful command of Spanish and Portuguese, then joined Sir Arthur Wellesley in Portugal in 1808. After landing at Mondego Bay on the 6th August, Guthrie struggled to find a mule. To help him, he commented that he had, “…. two one-handed men, attached to me, whose hands I cut off, after maiming themselves in America. These fellows could saddle a horse or mule nearly as quickly and as well as if their hands had not been amputated”. So began Guthrie’s Peninsular adventures. He was present at Roliça and Vimeiro, where the battalion suffered, in the former, heavy casualties (193 killed, wounded or missing). At Roliça, he tended the injured of the 9th and 29th regiments. This included a group of men, with wounded arteries. From this battle and later, from Albuera, he salvaged some specimens of these injured blood vessels. These he sent home to Dr Hooper, who published Guthrie’s observations on arterial injuries.

At Roliça, in August 1808, while amputating at the regimental aid post, a tourniquet buckle broke. Guthrie compressed the haemorrhaging artery and found excellent control of the bleeding by digital pressure at the groin on the main femoral artery. He rarely used the tourniquet again.

At Vimeiro four days later, our surgeon was shot in both legs by a musket round. After the passage of the Douro in May 1809, where Wellesley outwitted Soult, Guthrie, temporarily separated from the 29th, was riding up to the front with a battalion of Portuguese caçadores, to join his unit. The grenadier company of the 29th were ordered about face and made ready to fire on the Portuguese, mistaking them for French troops. Guthrie, in alarm rode out in front of the Portuguese and threw open his blue watch coat, so exposing his red tunic. He shouted, “The doctor and the Portuguese!” Mercifully, this deterred a British volley. As the skirmishers of the 29th advanced, Guthrie noticed a French field piece stuck in a lane to his left. Being the only mounted officer he charged down on the gun, the artillerymen running off, and cutting the traces of the large leading mule – which he took as a prize – he handed his gun over to a sergeant and a file of men. Sir John Sherbrooke, a divisional commander, was highly amused at the doctor’s triumph.

At Talavera, Guthrie collected all his battalion casualties into his own field hospital. After the retreat of the British army across the Tagus, near the bridge at Arzobispo, the marching wounded were collected, at the convent of Deleytosa, near Truxillo. Guthrie was appalled at the indiscriminate amputations (especially of the arm), which took place here. He made formal complaint and for this criticism he was to make enemies. He was keen to retain the arm whenever possible – only recommending amputation for the more devastating round shot injuries. Sir Hussey Vivian had asked to see Guthrie after he had sustained a wound of his arm, following the action at Toulouse in 1814. Surgeons had advised amputation, but Guthrie conserved the cavalry commander’s arm. Years later, introducing Guthrie to his second wife, Vivian said, “I introduce you to Mr Guthrie to whom you and I are both indebted for the arm on which you are now leaning”.

In the autumn of 1809, Guthrie almost died from typhoid fever between Merida and Badajos, on the plains of the Guiadiana, which required months of convalescence. In January 1810, having been promoted to acting (staff) surgeon to the forces, he was attached to the 4th division. Now a hospital doctor and after 8 year’s service with his battalion, he sadly said his farewells. Such was the esteem of the 29th for its surgeon that they presented him with 150 guineas worth of silver plate.

A year later, as one of the few staff surgeons at Albuera (which translates as the village of the mills) fought on May 17th 1811, he was stretched to the limit. His only assistant staff surgeon – Mr Bolman was killed, when a round shot hit struck him on the chest. Guthrie had only the battalion surgeons to help him. Guthrie took position near a German battery. Dr Stamford of the 29th requested permission from Guthrie to amputate the thigh of a gunner who had been struck by a round shot. Guthrie refused – a tourniquet was applied to the gunner’s limb and Stamford was sent to his battalion (which sustained around 400 casualties). Guthrie had correctly predicted the main attack on the Allied right and that the casualties would be heavy. The battle was over by 3 o’clock. It rained all night – compounding the misery of surgeons and patients alike. The roofing materials from the village house had been stripped for firewood and there was no shelter. Men were so desperate that they burnt wooden musket stocks, collected from the field. It was after this action that Guthrie emphasised that, when an artery was injured and the patient shocked, just tying off the bleeding vessel above the defect was insufficient. Many army surgeons had done this purely for speed and from the teachings of the celebrated John Hunter. Guthrie taught that the bleeding would continue from the lower (untied) end. So he taught that the artery should be ligated above and below the injury.

The 3000 casualties were evacuated to Valverde, Olivença, Jurumenha and Elvas – a dozen kilometres or so away. In his makeshift field hospital and working tirelessly for 18 hours a day he slogged away for 3 days. Guthrie only had 4 wagons.

He was then present at the three sieges of Badajos and that of Cuidad Rodrigo, also at Elbodon, Sacaparte, Sabagul and Salamanca. At one of the first two attempts to take Badajos (in May 1811), he was startled at a personally aimed round shot passing between his back and his horse’s tail! He doffed his hat to the French gunners and cantered off!

He was to have a notable casualty to consult on at Cuidad Rodrigo on January 19th January – Robert Craufurd – commander of the Light Division. He was shot through the right chest and died of infection and effusion into his thoracic cavity. Guthrie was not only consulted on the case, he performed the dissection (post mortem).

Before the forts at Salamanca, Guthrie rode out with an officer of the 23rd, who was wearing a new red tunic and mounted on a white horse (the young man was clearly out to impress ladies –the Salamanqiñas). A round shot landing just under Guthrie’s mount almost destroyed man and horse. Tragically, this young officer was later disembowelled by a case shot round and beyond help when Guthrie reached him. Following the main action at Salamanca, the local Spanish Junta, refusing to treat the 3-400 French casualties and were violently chastised by Guthrie. The French were deeply moved by Guthrie’s humanity and signed a memorial, which he modestly used to light a lamp as he considered the incident closed. He performed an important surgical procedure after Salamanca. A soldier had a grossly swollen leg from a streptococcal infection (erysipelas). So tight were the tissues that the leg was becoming gangrenous from lack of blood supply. Guthrie cut a long incision relieved the tension, the blood flow was restored and the leg was saved.

After all the above actions, Guthrie was senior surgeon in charge of the casualties.

On the 11th October 1812, he was brevetted as Deputy Inspector of Hospitals, principally in charge of Rowland Hill’s division, with his base hospital at Madrid, which Wellington had occupied in August. The Duke later set off to besiege and reduce Burgos.

When any medical issues in the Peninsula are considered, we cannot ignore Dr (later Sir) James McGrigor. He had arrived in Lisbon in January of 1812 and replaced Dr Franks. McGrigor had some daunting tasks – firstly to improve the hospital stations, secondly to redistribute surgeons to the front and soon to evacuate as many of the sick and wounded before the Duke commenced his difficult retreat from Burgos, back to Portugal. Guthrie had to perform a similar evacuation from Madrid (around 800 from hospitals and with 2000 sick on the march).

During this withdrawal, when the casualties reached the bridge at Alba de Tormes, Guthrie had arranged for some battalion surgeons to take the lesser wounded back to their units, whilst the remainder were sent to Cuidad Rodrigo.

In 1813 Guthrie started to use a long leg splint for fractures of the thighbone – thus preventing some of the bent up deformity often resulting from this injury. The long splints were well ahead of their time and crossed two joints, above and below the fracture – essential for the management of this serious injury.

By efficient evacuation, use of prefabricated wooden hospitals and the dispersal of the less severe cases to their regiments, McGrigor and Guthrie and their colleagues were able to re-inject about a division of fighting men back into Wellington’s army for the campaigns of 1813 and 1814. This monumental effort was one of the seminal events that brought McGrigor and his staff into the trust of the Duke.

Guthrie was now dispatched to Lisbon to be Principal Medical Officer to the medical “garrison” there. With great ignorance of the local conditions and individual surgeons’ abilities, the authorities back in Britain refused to gazette Guthrie’s acting rank. He was too young. This irritated the Duke, who wrote in his despatches from Frenada (January 1813), “What interest can I have in these concerns, – ‘till I saw Mr Guthrie the other day in the hospital at Belem, I do not believe I ever saw Mr Guthrie; although, from his reputation in the army ever since it came here, I intended to have made him surgeon to head quarters when Mr Gunning was promoted, if he had not been recommended for promotion in another manner: —“ Guthrie went on to comment, “that he considered his conduct as deserving the imitation of the whole army, and that he might rely upon his promotion being confirmed”.

He was moved north from Lisbon to Santander, to superintend the general hospital there. This hospital was a major centre for the casualties from the battles of Vitoria, Pamplona and the Pyrenees. Such was the parsimony of the British government, that his brevet DI rank was not confirmed until 1814, by a personal directive from the Duke of York. This commission was not backdated for payment.

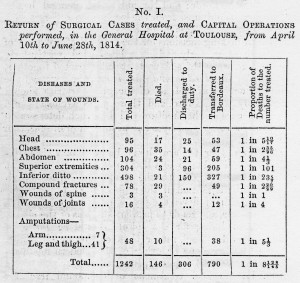

After the Battle of Toulouse, in April 1814, he was the senior surgeon at the general hospital there, responsible for around 1300 casualties. If anyone now wished to doubt the effectiveness of the medical department, here it was that those concerns would be dispelled. Eighty-eight per cent of men admitted to the hospital, were transferred, or walked out – discharged or cured. Bearing in mind the lack of anaesthesia, antisepsis and good field practice, these are truly impressive results.

Of 1242 wounded or operated ORs and NCOs, in Guthrie’s general hospital there were 146 deaths (12% mortality).

The end of the war marked the apogee of surgical skills in the British Army Medical Department, which was not to be surpassed even in the Crimean War, 40 years later. Little now could be improved until the advent of antiseptic surgery and anaesthesia. After making an unbelievable sacrifice of duty and commitment – epitomised by most of Wellington’s surgeons, Guthrie was placed on half pay, and now “exerted himself in support of his family”, who he had not seen for 6 years. He realised that surgical practice at home had not stood still so he diligently attended surgery and anatomy lectures at the Windmill School and several of the London hospitals.

The return of Bonaparte to France in 1815 brought the Allies to the plains of Waterloo. Reluctant to return to full pay in His Majesty’s service at the last throw against Britain’s mortal enemy, he overcame the desire to remain at home and succumbed to the temptation to help since he could, “ — take that opportunity of verifying certain points of surgery which were not satisfactorily established”. He volunteered to assist in Brussels for a short while. He received encouragement from Sir James McGrigor, appointed Director General of the Army Medical Department merely five days before Waterloo.

George Guthrie arrived in Brussels on 3rd July and left on the 10th. There were five principal hospitals in Brussels – the Minimes, Hôtel du Nord, Corderie (French), Façon, and the Augustines. There were other lazarettes – the Annunciata, Elizabeth and the Gens d’Armerie. Various staff surgeons vied with each other for Guthrie’s attention. His role was that of a consultant and he only operated on two patients. The first was a soldier with persistent bleeding from a wound in the calf. Guthrie cut down deeply and secured the bleeding artery.

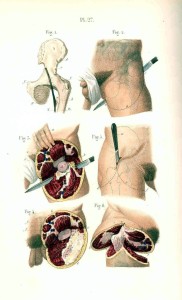

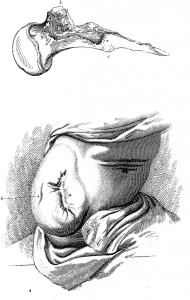

The other case is one of the most celebrated in the annals of British military surgery. The patient was Francois de Gay, of the 45 Regiment de Ligne, a French prisoner of war. He had received a case round in his right buttock, which had shattered the upper end of his femur (thigh-bone) and exited in the groin. De Gay had lain on his back for 4 days and unable to move, had survived by turning his head to lap water from a puddle. There was no possibility of carrying out any form of amputation except through the hip joint (disarticulation). Dominic Jean Larrey had performed this formidable procedure seven times. He had had only one survivor – after the battle of Vitepsk in 1812. In the British army, a certain Mr. Brownrigg, a veteran of the Peninsula and Waterloo and surgeon to the forces also had one survivor, but the case was not documented. Brownrigg’s patient had been injured on the 29th December, near Merida, a year earlier. Having sustained a deep thigh wound from a musket ball, he was disarticulated on the 12th December 1812. The patient apparently did well and was said to be alive near Spalding in Lincolnshire.

De Gay had been offered this operation as a last desperate gamble to save his life. He was terrified and at first refused. Realising that Guthrie was the only man bold enough to carry out the procedure, he consented. Guthrie, assisted by Dr John Hennen (the author of “The Principles of Military Surgery”) and Mr Collier, undertook the operation on July 7th – 19 days after injury. The patient was propped up on the end of a sturdy table and supported (restrained) from behind. No alcohol or anodyne (pain-relieving drug, eg tincture of opium) would have been given. With the injured leg supported, Guthrie thrust down the blade of a capital knife through the thigh on one and then the other side of the femur in the upper thigh. By firm cuts outwards, two skin flaps were so fashioned – these would ultimately cover the wound. Any bleeding that ensued was controlled by finger pressure of the assistants. The hip joint was stressed by moving the leg outwards and the joint capsule and ligaments divided. The leg was then removed. Blood loss was around 24 fluid ounces (720ccs).

The patient recovered and after Guthrie left Brussels, was transferred to the York Hospital in Chelsea. He remained under Guthrie’s care until he was returned to the Hôtel des Invalides – with a pension at the insistence of the Duke of York. De Gay was the only survivor of this capital operation in France.

One other patient was referred to George Guthrie before he left Brussels. A soldier had been shot, a ball had entered his bladder, where it became the kernel of a calculus (bladder stone). The medical staff in Brussels assured Guthrie that the patient would be referred to him in London. Here Guthrie removed the bladder stone in less than 5 minutes and the patient did well. The procedure – underlying the very public nature of surgery at these times – was witnessed by an adjutant, the Quartermaster General and Sir James McGrigor.

After the war, he had few friends and no employment. Guthrie worked gratis in the York Hospital as an honorary consultant, whilst he built up his reputation and private practice. The York Hospital was dismantled two years later. In 1815, he had purchased no; 2 Berkeley Street, later moving into nos. 4 and 5, which originally housed offices of the Army Medical Board. Guthrie, with the patronage of the Dukes of York and Wellington, founded the Royal Westminster Eye Hospital. As a mark of the governors’ esteem, in 1823, he was appointed as 4th Surgeon to the Westminster Hospital. Elected to the Council of the Royal College in 1824 (the youngest ever appointed), he took a chair in anatomy and surgery the following year. He was three times elected President of the London (later the English) College (1833,1841 and 1854) – a remarkable achievement for a man with a military background.

He spent most of his time as council member and president promoting justice, openness and equality for surgeons. He toiled away to promote medical support for the “sick poor” and had been instrumental in the passing of the Anatomy Act of 1832. He was appalled at the lack of a chair and school for teaching young Military surgeons field surgery, in so many ways different from civilian practice. There was such a set up in Edinburgh, where Professor John Thomson had taken on the post of Regius Chair in Military Surgery (from 1806 to 1822). Thomson and Guthrie (the latter for 30 years) delivered free lectures to packed military audiences in Edinburgh and London respectively. The major problem for young surgeons was the total lack of exposure during training to severe battle casualties or the management of hundreds of men with contagious diseases, such as typhus, typhoid (remittent fever), measles, smallpox and dysentery. The skill of surgeons in the armed services was frequently stretched to the limit, since adequate accommodation, dressings, hygiene and diet were often just not available.

Guthrie was elected a member of the Royal Society in 1827. He had turned down a knighthood and demurred over the award of the Order of the Guelph. By their pristine appearance he must have barely ever worn his medals.

His contributions to military surgery were pre-eminent since he reduced many problems to the simplest solutions, using common sense and refusing to be dominated by traditional dogma. He jealously guarded his patients and was an enthusiastic teacher. His talents as a field surgeon and the wealth of experience led to publication of a textbook “Commentaries on the Surgery of the War”, which went through many editions and was to prove of immense value to the Army Medical Department in the Crimean campaigns. There is some evidence that the technical skills achieved by surgeons at the end of the Napoleonic Wars were probably better than those of the Crimean War. What destroyed the British army in the latter campaigns was disease and deprivation – just as it had in the former. In Guthrie’s war only one in five hospitalised patients perished from battle-related injury.

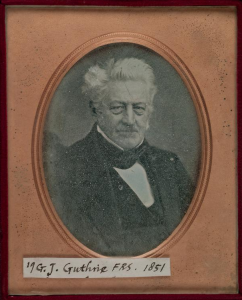

Daguerreotype of Guthrie in later life – one of only two such “photographic images” of a British military surgeon of the Napoleonic Wars.

(Courtesy of the Royal College of Surgeons of England)

Guthrie spent many of his latter years improving surgical education. He had seen the full horrors of war and used his impressive surgical experience opportunity to best advantage. Between 1808 and 1814, he was said to have personally treated around 20,000 wounded men. As one biographer wrote, “Mr Guthrie indeed appears to be as much a soldier as a surgeon”. Justifiably nicknamed, “The English Larrey” – he was truly the father of British military surgery. He died of cardiac problems, aged 71, on his birthday 1st May1856 and was buried at Kensal Green. He had married twice, had three children – one of whom became a surgeon – but they left no issue.

Shrewd, outspoken but kind at heart, he possessed the true attributes of a great surgeon, a lion’s heart, the eye of an eagle and the fingers of a lady. His memory is kept alive by the RAMC by the award of the Guthrie Medal to outstanding civilian consultants to the Army.

______________________________________

MKH Crumplin MB BS FRCS (Eng and Ed) FHS FINS, Hon. Curator at the Royal College of Surgeons of England; archivist to the Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland

‘Guthrie’s War’ – a tale of one of Britain’s greatest surgeons and possibly our most meritorious military surgeon – published by Pen and Sword; ISBN 078 1 84884