The Many Faces of Napoleon: ‘Little Boney’ or Napoleon le Grand?

April 21, 2015 - Alwyn Collinson in Guest Articles, News & Blog Posts

This is a guest article by Sheila O’Connell, British Museum Curator. See ‘Bonaparte and the British:

prints and propaganda in the age of Napoleon‘ at the British Museum until 16 August 2015.

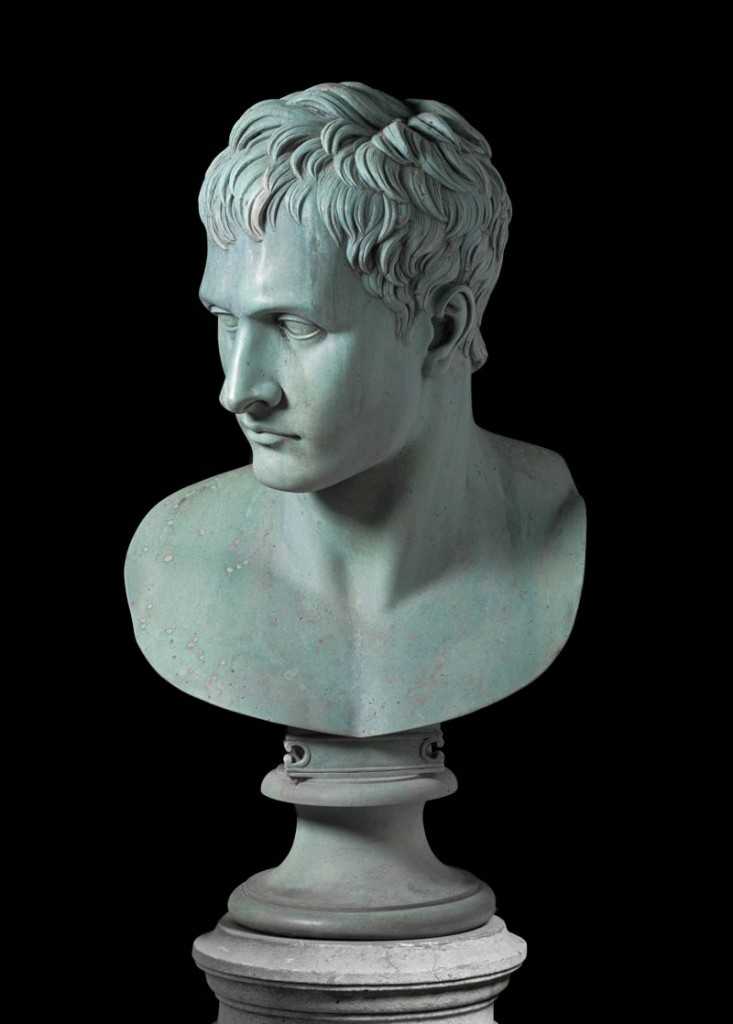

On a Tuesday at the end of January, we unpacked the marvellous large bronze head of Napoleon Bonaparte made by Antonio Canova for Lord and Lady Holland in 1818. It currently sits in pride of place at the beginning of the exhibition Bonaparte and the British: prints and propaganda in the age of Napoleon, on display in Room 90 until 16 August 2015. The Hollands set up the Canova head in the garden of Holland House in Kensington after the former emperor had been exiled to St Helena. In so doing, they signalled they demonstrated their admiration for the man who had influenced the course of European history for 20 years.

Most of our exhibition consists of satirical caricatures showing Napoleon in a far from flattering light. These started to appear in 1797, once the young general became internationally known after his military successes in Italy. At first, when his face was still unfamiliar, he was portrayed as a wild moustachioed bandit humiliating the Pope and driving out the Austrian imperial forces. Then in Egypt in 1798, he met his first defeat at the hands of the British when Horatio Nelson destroyed most of the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile. Napoleon, an intellectual as well as a brilliant soldier, had taken more than a hundred scholars with him to study the little-known country. The ancient objects that these scholars acquired included the Rosetta Stone, which came to the British Museum along with other treasures in 1802.

In 1799, Napoleon became First Consul of France and the following year he led his army across the St Bernard Pass to drive the Austrians out of Italy again. Peace treaties were signed with the continental European powers and eventually in 1802 between Britain and France. After nearly a decade of war, Britons flocked to Paris. James Gillray’s portrayal of the meeting of a fat Britannia and a sly Frenchman reflects the lack of trust between the two countries that would lead to an outbreak of war before long.

James Gillray (1756–1815), The First Kiss this Ten Years! Hand-coloured etching and aquatint. Published by Hannah Humphrey, 1803. 1868,0808.7071

From 1797, Gillray had been receiving regular payments from the government to ensure that his talents were used to support official policy. His most lasting contribution to the denigration of Napoleon was his invention in 1802 of ‘Little Boney’, an aggressive bully of tiny stature. It was at that time that Britain’s fear of French invasion became focused on Napoleon who was in fact about 1.67m tall (5 foot 6 inches). It is thanks to Gillray and his caricaturist colleagues that history remembers Napoleon as a tiny man with huge ambitions.

As well as looking at Napoleon’s career through the eyes of caricaturists, the exhibition shows examples of portraits made for his admirers and expensive prints made to record the famous battles of the war. The cheaper end of the market was also targeted by the print publishers. The triumph of Nelson at Trafalgar in 1805 was followed by the publication of a huge number of prints mourning the great admiral’s death. These include mass-produced prints aimed at the sailors who hero-worshipped Nelson.

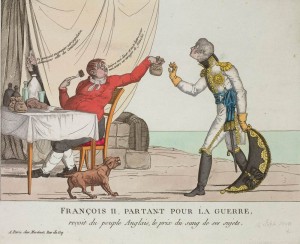

Napoleon’s great victory at Austerlitz, shortly after Trafalgar, received less attention in Britain. At this point in the exhibition we show examples of Napoleon’s own print campaign against the British. He ordered French printmakers to show John Bull, the archetypal Englishman, handing bags of gold to the Austrian emperor to fund his army. In another pair of French satirical prints, William Pitt, the British prime minister, is shown dreaming of victory and waking to defeat.

Anonymous, François II partant pour la guerre (Emperor Francis II leaving for war). Hand-coloured etching and aquatint. Published by Aaron Martinet, 1805. 1868,0808.6905

In 1807, as Napoleon’s army entered Spain, Britain rallied to the cause of the Spanish guerrillas as they tried to defend their country. Caricatures by Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson were copied in Spain to encourage the resistance that continued for years. The next profusion of British satirical prints came with Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow in the winter of 1812. By then, Gillray had suffered from a mental breakdown and his place as the leading anti-Napoleon caricaturist was taken by the young George Cruikshank. News of Napoleon’s army struggling through the snow of the Russian winter inspired Cruikshank to high comedy.

In 1813, the tide began to turn. Prints satirising Napoleon had previously been harshly suppressed in the countries that he dominated, but in that year they began to appear all over Europe. A particularly popular example showed a devil rocking a baby Napoleon. There were around 20 versions of this image, one of which was made in London by Thomas Rowlandson and given the title The Devil’s Darling.

Thomas Rowlandson (1757–1827), The Devil’s Darling. Hand-coloured etching, 1814. Published by Rudolph Ackermann, 12 March 1814. 1868,0808.8116

Napoleon’s crushing defeat at Leipzig in October 1813 and the crossing of the Franco-Spanish border by the Duke of Wellington’s army, led to Napoleon’s abdication in April 1814. He was exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba, but returned in less than a year. His renewed rule lasted only 100 days before the final Battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815. Lifelong exile to the remote south Atlantic island of St Helena followed.

As soon as Napoleon was removed as a threat, Britain began to perceive him as something of a hero. His most prominent admirers were Lord and Lady Holland but, as the French ambassador to London later recalled, by 1822: ‘Souvenirs of Bonaparte were everywhere; his bust adorned every mantelpiece; his portraits were conspicuous in the windows of every printseller’.

Our exhibition aims to show both sides of the British response to Napoleon. On the one hand, the view of him as the devious and belligerent ‘Little Boney’; on the other, admiration for his military prowess and administrative genius by those who hoped that he might rescue Europe from the excesses of the old hereditary regimes.

The exhibition Bonaparte and the British: prints and propaganda in the age of Napoleon is on display in Room 90, the Prints and Drawings Gallery, until 16 August 2015.

The exhibition catalogue by Tim Clayton and Sheila O’Connell is available from the British Museum shop online.

The British Museum have contributed several satirical cartoons to our web series Waterloo in 200 Objects. See The Plumb Pudding in Danger and The Devil to Pay.