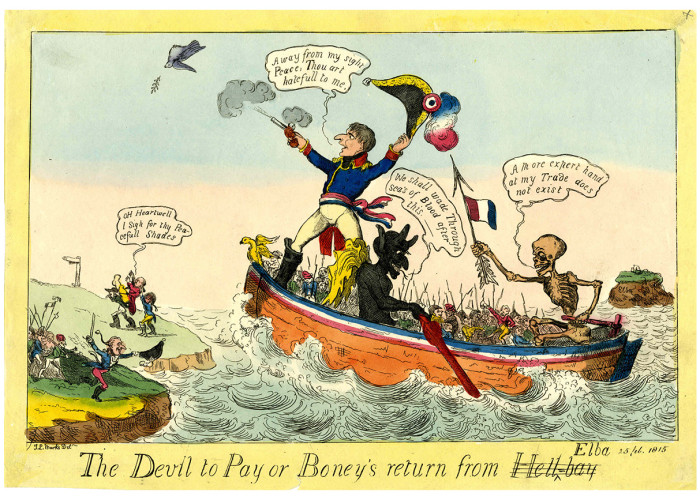

The Devil to Pay or Boney’s Return from Hell-Bay

This satirical print, created and engraved by John Lewis Marks, captures the immediate popular response to Napoleon’s return from Elba in March 1815, and the resulting international response to his re-establishment of power in France.

Notwithstanding Napoleon’s own avowal that he had no warlike ambitions upon returning to power, he was swiftly branded an outlaw by the coalition of Great Powers ranged against him because they all feared that a Napoleonic resurgence would mean a renewal of the hostilities that had wracked Europe for the best part of the previous quarter-century. It is for this reason that Napoleon is shown to be in league with the Devil and Death, both of whom comment favourably on his return from exile and the calamities that they confidently predict will ensue. The fact that Napoleon himself is depicted as shooting the dove of peace is a further, if less than subtle, reinforcement of this stance.

Although Marks depicts Napoleon’s return as a terrible thing, he does also accurately portray the enthusiasm with which he was received by many in French society. A large welcoming crowd gathers to meet him, led by a long-nosed general or marshal, possibly intended to represent Michel Ney. Ney was one of the first to declare himself in favour of Napoleon, and later fought under him at Waterloo. Meanwhile, in the background, Louis XVIII, shown as too fat to walk, is being carried into a renewed exile.

Marks was not one of the well-known caricature artists, only setting himself up as an independent artist-cum-publisher in 1817, but follows many of the conventions utilised by others working in the same field. Other than the central figures, Napoleon’s followers are depicted as short of stature: imps to the larger satanic figure of their Emperor. Napoleon himself is referred to as ‘Boney’, a contraction of his surname that was almost universally employed in prints of this nature, handily enabling frequent allusions to be made to death or other skeletal figures.

In the era before photography, prints like these were the only visual representation of current events widely available to the public: from high quality coloured impressions like this one, bought by collectors, to cheaper reproductions pasted on tavern and coffee house walls. Even the poorest in society could view them on display in the windows of the print shops from which they were sold.

Sources:

George, M. Dorothy, Hogarth to Cruikshank: Social Change in Graphic Satire. London, Viking, 1967.

Biographical Details of Marks: http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/term_details.aspx?bioId=115809

-

Curatorial info

- Originating Museum: British Museum

- Accession Number: Museum number 1868,0808.8184

- Production Date: 1815

-

Use this image

- Rights Holder: British Museum

- License Type: All Rights Reserved

Find it here

This object is in the collection of British Museum