“Keep Hougoumont” – at what price?

The price of Hougoumont. Mick Crumplin gives a detailed account of the human cost.

My first visit to Ferme d’Hougoumont was almost fifty years ago, in the early 1960s. I knocked on the door of the gardener’s house (during the battle, occupied by the gardener, Guillaume van Cutsem and his five-year old daughter) and was shown in and around by Monsieur and Madame Temmermans. It was a working farm then, and was in pretty good shape. Now it is a decaying, sad remnant, a stark ramshackle collection of still deteriorating part-painted brickwork that had been a staunch bastion of Allied defiance against Bonaparte’s army at the Battle of Waterloo. The chapel has been nobly restored, but even that has been desecrated.

One could not imagine a more fitting site for Britain’s remembrance of the Allied defence – for Hougoumont was a miniature battle itself, stuck out precariously in front of the right-centre of Wellington’s line. Thousands of men died and were burned or badly hurt, either assaulting the old Brabant farm or defending it, as though the whole outcome of Europe depended upon it. When Henry Paget, Lord Uxbridge asked the Duke what was the key issue of the day, the Commander replied ‘Keep Hougoumont’. Wisely or unwisely, disregarding Soult’s suggestion of a flanking attack around Wellington’s right line, Bonaparte demurred and ordered Hougoumont to be taken, whatever the cost.

The farm had to be strengthened by the Allies and perhaps the first medical issue of note was the enormous physical effort required to shore up the farm’s defences during the sodden night of the 17th June. The 200-300 men making up the light companies of the Coldstream and 3rd Foot Guards, first posted to the chateau, had recently acted as part of the rearguard on the retreat from Quatre Bras and were completely exhausted. They had had little food, yet some small respite from the storm of that night, occasionally sheltering in the outbuildings of the farm. But the strength of Wellington’s defence depended on the robust state of the farm complex. So, tired, hungry and wet, these men, assisted by all the Guards pioneers and some German pioneers from La Haye Sainte, set about smashing loopholes, building fire steps and barricading gates. Ammunition had to be stored in the main chateau. The next morning, the garrison was reinforced by Brunswick Jägers, as well as 800-900 men from the 1st Battalion, 2nd Nassau Regiment, and later – around 1200 hrs – by other German troops (Hanoverians of the Feldjägers, Lüneburg and Grübenhagen units), who had to be prepared to rise to the immense physical and mental challenge of seven hours intense combat.

But, the defence of Hougoumont was purchased at great cost. Ultimately, including reinforcements, the farm was defended by around 4,000 men, with other units in support. There were seven tough French assaults against the buildings, garden and orchard, between 1130 and 1630 hours on the 18th June. Prince Jerome’s first attack alone cost the French 6th Division 1,500 casualties. Accurate final casualty figures are hard to come by, but about 1,500 Allied dead and wounded (including 584 Foot Guards) and upward of 4,000 French would not be far short of the mark. Of 1,852 officers and men of the 1er Léger Regiment, which was a key unit assaulting the farm, only 607 mustered on 24th June. Not all of these men missing were casualties, however – many, with Royalist tendencies had absconded after the final rout.

One great protective feature of the surrounds of the farm, which seems in retrospect a critical issue, was the moderately dense woodland situated on the southern aspect of the complex. It presented somewhat of a barrier to French heavy ordnance, which could have been brought up to pound and quickly destroy the long brick wall alongside the formal garden. Without the cover of these woodlands, casualties on both Allied and French sides would have been higher and the farm might not have held.

Focussing on the Allied casualties, if we assume a 4:1 wound: kill ratio, this would leave around 200-300 killed, but about 1,200-1,300 injured men for the surgeons. This demanded at least two to three battalion medical staff, perhaps with one or two more, joining with reinforcements later. Amputees, seriously injured, or dying men would not immediately have been moved beyond the confines of the farm, before or after surgery. An example of this was Adjutant Captain Noel Harris, brigade major serving under Sir Hussey Vivian, hit by two musket shots, near Hougoumont. He was later operated on within the farm complex and was moved to Brussels, when fit enough. He received one ball through his right side and another shattered his right arm – for which he suffered an amputation.

Captain Noel Harris’ coat, showing ball entry damage in right sleeve (cut open for surgery) and right side.

(Courtesy of Mr Alan Harrison)

Defending the farm meant crouching behind low walls or hedgerows, mounting some fire steps (made from household furniture, wood or bricks) or manning loopholes in the taller walls running on the south and west faces of the garden. There is some evidence that the structure of the south wall, on its internal face was different to today. The cover afforded by these high walls was clearly useful to the Allied soldiers since the extant records relating to the 3rd Foot Guards show that the majority of their casualties were sustained in the orchard and the wood. Even if Allied defenders couldn’t get up onto a fire step (most likely sited at the west end of the wall, near the gardener’s house, it is unlikely the whole of the long wall was provided with fire steps) or behind a loophole, they could wait for the struggling Frenchmen to heave themselves up on comrade’s shoulders. Before a French musket could be lifted and discharged over the wall and down into the garden, the head, neck and torso of the enemy presented close and lethal targets to Allied muskets. Such an example of this was seen when a French grenadier, standing on a comrade, aimed his musket over the wall at Colonel Wyndham, who handed a musket to Corporal Graham (both men were Coldstreamers), which successfully discharged a lead ball, probably into the Frenchman’s brain. Men struggling over the high wall, presented lethal and relatively easy targets with their head and neck – also an easy focus for the firelock butt or bayonet. Between the high brick walls or hedges and the woods was some clear land, risky to cross for both sides – a veritable killing ground.

The medical aid here was somewhat compromised by the isolated nature of the outpost. Any British and German surgeons present probably used the main chateau buildings for a while, as the field aid post. When this, the stables and the great barn burned out, the injured were transferred into other buildings and byres – mostly on the west and south walls – also into the gardener’s house and buildings, which form the most intact dwellings today, at the south aspect of the farm. For the Allied casualties, the nearest field hospital was at Mont St Jean Farm, nearly two hazardous kilometres away. In the early afternoon, during a lull in the assaults, after Lieutenant Colonel Francis Home’s reinforcement of the orchard, the North Gate was opened and the lightly wounded men were taken out to the rear, along the hollow way, up onto the ridge and onto Mont St. Jean field hospital.

For the French assault troops the field hospitals at the farm of Rossome or Auberge Le Caillou, were also a long way back. Napoleon’s casualties would have to have been cared for in adjacent cottages or hovels – the farm of Mon Plaisir – for example.

Medically speaking, we have scant hard data to relate, since few accounts give much information as to the medical staffing, care and outcome of the casualties in the chateau. Normally a reasonably experienced junior surgeon was taken into line, leaving the senior battalion doctor more securely in the rear, but the isolated nature of Hougoumont mandated more senior surgical support. Although there seems to be no extant account of surgery in the farm, it is inconceivable that there would be no battalion medical provision there, given the number of casualties referred to above. Firstly, it was risky and too far to evacuate any but the walking wounded, all the way back to Mont St. Jean and, secondly a significant number of badly hit men urgently needed immediate and experienced surgical treatment and that thirdly, there was a relative amount of ‘safe’ cover in the buildings – for we know that Brigade-Major Noel Harris was later amputated in the farm.

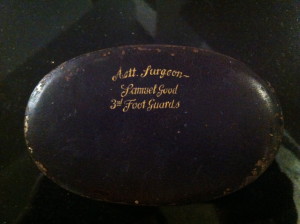

If we consider the two British regiments represented at Hougoumont, Surgeon Samuel Good of the 3rd Foot Guards, (to whom a special tribute and gift was later made – a regimental King’s Colour was presented to him for his long and devoted service to the regiment and, no doubt, for his labours during the battle) states in an account of his part in the action, that he was stationed in another large farm a few hundred metres behind Wellington’s ridge (Mont St. Jean Farm). Thus it was possibly Surgeon William Whymper of the Coldstreams, who was the senior medical man there. All things considered, I strongly suggest that there must have been one to three surgeons within the chateau precincts.

A tin container – for field instruments (stamped as ‘Assistant Surgeon’) (Courtesy of Mr Gary Barnshaw)

There were two assistant surgeons for the 3rd Foot Guards. Assistant Surgeon Hanrott could have been present at Hougoumont, but since the second assistant surgeon of the 3rd Foot Guards, John Ward, was in Brussels, (he had been put in charge of a detachment of a sergeant and four privates to mind the heavy baggage and hospital equipment, and assisted with the many incoming casualties in the city), Hanrott probably remained back with the rest of the battalion on the ridge or, less likely, in the chateau with the Light Companies.

Thus it seems perfectly feasible that William Whymper, surgeon to the Coldstreams and one of his two assistant surgeons (either William Hunter or George Smith) were there, in addition to a surgeon or two from the German units serving around the farm. Sadly, relevant parts of Hunter’s diary, written just a few days after the battle were destroyed.

Assistant Surgeon William Hunter, Coldstream Guards – in later years.

(Courtesy of the Royal College of Surgeons of England)

The type of surgery carried out in the house, barns or stables was principally, exploration and tidying of wounds, controlling haemorrhage with bandages, ligature or amputation, splinting fractures, extracting missiles and perhaps a few efforts to trepan a patient with a depressed or compound skull fracture.

Typical early nineteenth century amputation set.

(The set contains knives, saws, a screw tourniquet, ligatures and a tenaculum for securing blood vessels – author’s collection)

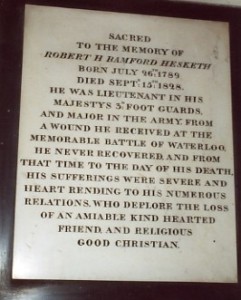

A few injuries serve to illustrate the level of surgical care required in the chateau. After the North Gate break in by the French infantry, an Hanoverian officer named Lieutenant Wilder, who was being chased by some Frenchmen, grasped the handle of the door to the farmer’s house, but his hand was hacked off by a French pioneer. Ensign David Baird of the 3rd Foot Guards was struck on the jaw bone by a musket ball, which knocked out some teeth on the opposite side of his mouth and eventually extruded with some teeth embedded in it. To staunch the blood flow in the first instance and then to maintain Baird’s airway would have required an experienced surgeon. Lieutenant Robert Hesketh of the 3rd Foot Guards was another victim, also shot in the neck. He died prematurely of this severe wound, in 1828.

Some wounded could wait for surgery or further dressings. For example Lieutenant Daniel MacKinnon, the historian of the Coldstream Guards was hit in the knee by a spent ball, but remained in the chateau until after the action, whence he was transported to Brussels with some other wounded officers by carriage.

One poignant, yet uncorroborated and probably apocryphal story, concerned a remarkable injury affecting the wife of Private George Osborne of the 3rd Foot Guards. She had married George at Engien on the 23rd April 1815. She worked all day of the 18th with the wounded, tearing up her own clothing for bandages. She had dressed Captain Edward Bowater’s wound on the battlefield and, was then wounded in the left arm and breast. She survived and was awarded the Queen’s Bounty for her bravery. I’m fairly certain this event would have taken place on the ridge, and have no evidence of women serving at Hougoumont – although I suppose we can never be sure.

Surgical scene, Hougoumont Farm. A rather sanitised model of an amputation about to be carried out by a surgeon of the Coldstream Guards.

(Author’s collection)

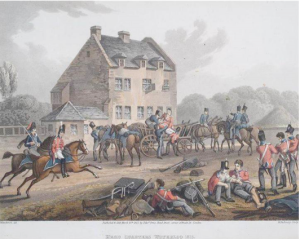

Around midday, French howitzers fired pitch or oil-filled carcasses into the farm, the roof of which had then caught fire. The fire spread through the main chateau building. The casualties being cared for there were evacuated – some were seen crawling out with their clothes ablaze. Sometime after 1300hrs, Lieutenant Colonel Home of the 3rd Foot Guards, had brought down two companies of Guards to assist with a counter attack. He barely had time to get out of the chateau, having just given orders for the removal of wounded officers from therein, where all were being choked and blinded with dense smoke.

There must have been a good number of burns to treat, both from a blazing haystack and the main house, which was defended until the burning floors and roof joists collapsed in the flames. The far seeing Duke had spotted the fire and sent a message down to the farm via an ADC, Major Andrew Hamilton. The Duke ordered men to stay in the burning house as long as feasible, then to move out and prevent the enemy from entering the complex via the burning ruins. There were reports of deaths in the burning main chateau building, as flames engulfed the victims. Some howitzer shells set more stables and barns alight – men screamed to be rescued, but in vain. These fires threatened Corporal (soon to be Sergeant) James Graham’s brother, Joseph, and at a fairly critical time, around the closing of the North Gate, James was granted permission to save his wounded brother from burning to death. In the farm’s chapel, the site of a recently despicable theft of the wooden crucifix with burnt feet, it was said that several wounded soldiers were sitting propped up against the whitewashed walls of the small religious chamber. The flames licked around the crucifix through the doorway and then they receded, presumably as the fire abated somewhat. Such a thing was considered a miracle by some of the soldiers trapped there.

Fig. 9 Wounded being evacuated from the main chateau building.

(Painting by Robert Hillingford – courtesy of fineartphotolibrary ltd)

There is evidence, from men who wandered into the farm after the battle, of many wounded of both sides, lying around in the gardens and orchard. Matthew Clay, the well-known diarist of Hougoumont, was ordered on the 19th to accompany a corporal back to the chateau, where, by the burnt haystack near the main building, he found several of his erstwhile comrades, whose bodies were intact, but had completely dried up.

Gradually casualties were evacuated via Waterloo to Brussels – many would have to have been tough to survive that jolting journey on severely congested chausées. The battalions soon moved off towards Paris. An NCO and several men in each regiment were temporarily left back to help with the wounded of their regiment. The care of the remaining injured was left to civilian doctors and the Medical Staff and their underlings. Many army and civilian surgeons flocked from Britain to Brussels and Antwerp to help.

It was the height of summer and bodies would soon have deteriorated. The dead were burnt and interred in various pits by locally recruited peasants supervised by medical staff.

Corpses from the action round Hougoumont being interred in a mass burial plot at the south side of the farm.

(From William Mudford’s ‘Battle of Waterloo’, 1817 – Author’s collection)

The main burial plot was a mass grave just outside the South Gate, where in fact there was for many years afterwards a midden. John Scott, a British visitor, who reached the farm the same month, reported that 600 bodies had been burnt and buried there.

One further medical issue of interest is an observation, to be made in a forthcoming publication by John Franklin, relating to a certain Ensign Hugh Seymour Blane, of the 3rd Foot Guards, who served at Hougoumont. During the great French cavalry assaults on Wellington’s line, Blane requested of his senior officer, Captain Douglas Mercer, to extend his men to the left to have ‘an effect’ on the cavalry’s flank. Mercer refused to issue such an order, fearing the risk from further local French attack. Blane was the son of no other than Sir Gilbert Blane, the great medical administrator and reformer of the Royal Navy, who had not only motivated many sensible health reforms in the service – vaccination and the eradication of scurvy, for example – but also had been involved in the decision to and process of withdrawing the British Army from the disastrous Walcheren Campaign in 1809.

When considering the possible plight of Hougoumont’s sad buildings today, one can only yet dream that sometime a fine memorial of one sort or another to the heroic and harsh sacrifice of the British, Allied and French soldiers during this monumental contest will evolve. Around 5,000 – 5,500 men of both sides had been badly hurt or died around the farm.

The burnt, hurt and exhausted men of the Allies who had defended Hougoumont had shown remarkable tenacity and had made a significant contribution to the great victory over Bonaparte’s great army at Waterloo. Surgeon William Whymper and his colleagues must also surely take great credit for their efforts on the 18th June 1815.

MKH Crumplin MB BS FRCS (Eng. And Ed.)

______________________________

Acknowledgements

I should like to acknowledge;

The permission of ‘Project Hougoumont’ for allowing me to reproduce this article on the Waterloo200 website. Also, John Franklin’s kind assistance in allowing me a preview of the excellent and well-researched forthcoming publication concerning the history of the 3rd Foot Guards, in particular their role during the fighting at Hougoumont. I also thank Mr Gary Barnshaw for permission to use images of Surgeon Good’s uniform and container, the Royal College of Surgeons of England for the image of Surgeon William Hunter and I am also very grateful to Alan Harrison for the use of the image of Noel Harris and his coat.