Billy Waters Earthenware Figurine

Theme: American war of independence (1775 - 1783), The arts in the Age of Revolution, American revolution, Challenging slavery: abolition and opposition, People in motion: exiles and opportunities

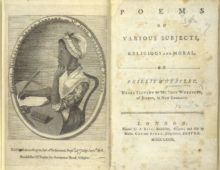

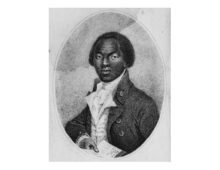

| William “Billy” Waters was an American-born sailor who gained popularity in the early 1800s by entertaining crowds outside London’s famous Adelphi theatre. Although he became quite well known as a street performer in his time, relatively little is known about Waters as a person today. Much of Waters’ life story comes from popular culture, artistic representations, and spectators who witnessed his performances. Some would exploit his image and celebrity to sell products that reflected cultural myths about poverty and race.

Waters was born in New York during the American Revolution, at a point when many enslaved African-Americans had fled to British lines, some to secure their freedom and escape abroad. Though Waters’ precise status is unknown, in 1811 at the height of the Napoleonic Wars, he was enlisted in the Royal Navy and served as an able seaman and later a gunner. His service in the British Navy reflected the increasing ethnic diversity amongst sailors during the Age of Revolution. The Royal Navy had long employed men of all backgrounds from across Britain’s growing empire, and had lately also impressed (forced into service) many American citizens. Life in the Navy was tough for Waters. His work was very physically demanding, and he was completely isolated from his family. While working aboard the HMS Ganymede, Waters suffered a serious fall, which resulted in the amputation of his left leg below the knee. Afterward, he was discharged, and he settled in London where he is recorded as having a wife and children. Like many Black servicemen, Waters received a pension for serving in the Navy. However, the sum was so little that he turned to busking to provide for his family. On the streets of London’s West End, Waters sang, danced, and played the violin, where thousands of people saw him perform in his distinctive costume of a large military hat with flamboyant feathers, and a naval jacket. During his performances, he would pivot around on his prosthetic leg and project his music above the noise of the busy city streets. His celebrity became so iconic that playwrights were soon representing a cartoonish version of him on stage, played by actors, which undermined his own art and livelihood. Many of these representations drew on negative stereotypes about race, disability, and poverty – turning Billy Waters from hardworking husband, father, or war veteran to the so-called ‘King of the Beggars’. In his final days, Waters seems to have been ill and financially desperate. He pawned his fiddle and entered the St. Giles Workhouse, where he died ten days later. Waters was buried in an unmarked “pauper’s grave” in the burial ground beside Old St. Pancras Church. Today, a blue plaque hangs on the corner of Dyott and Bucknall Streets in the London borough of Camden, honouring the site where Billy Waters lived with his family. This caricatured depiction of Waters is a ‘Staffordshire figurine’ made from ceramics. The Industrial Revolution meant that more pottery could be produced, and people had more money to spend, creating a demand for collectible luxuries. Potters in Staffordshire started creating figurines of important people at the time, including Queen Victoria! Therefore, although an inaccurate and problematic depiction of Waters, it represents his significance within British popular culture during the Age of Revolution, and the way that war, migration, and performance intersected.

Did you know…? Military records show that William “Billy” Waters served on the HMS Namur, which was captained by Jane Austen’s brother, Charles. |

- Related resources

- Enquiry Questions

-

Did you know..?

Military records show that William “Billy” Waters served on the HMS Namur, which was captained by Jane Austen’s brother, Charles.

-

Curatorial info

- Originating Museum: National Portrait Gallery

- Production Date: 1840

- Creator: Unknown

- Original record

-

Use this image

Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery. You can download this image for personal and educational use but please take note of the license type and rights holder information.

- Rights Holder: © National Portrait Gallery

- License Type: All Rights Reserved

- Related Objects