Exploring Black Histories in the Age of Revolution

October 29, 2020 - Richard Moss in News & Blog Posts

As Black History Month draws to a close we look at some of the Black Histories highlighted by the Age of Revolution with links to explore more.

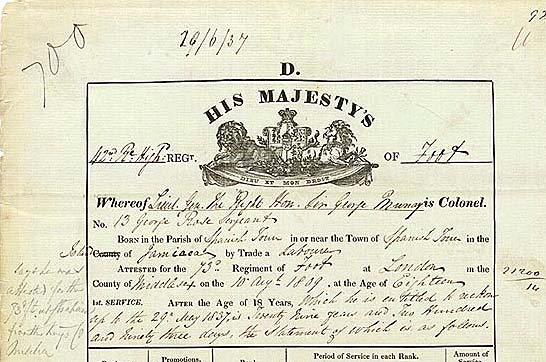

George Rose, Waterloo veteran

From our extensive Waterloo collection is the story of George Rose, a Black soldier at Waterloo.

Rose was born into slavery in Spanish Town, Jamaica in around 1791. By 1809 he had escaped to Britain and his discharge papers, held in the National Archives, show that at the age of 18 he enlisted in the 73rd Foot, British Army in London. At this time, previously enslaved Black soldiers became ‘freemen’ and were entitled to the same pay and conditions as White soldiers.

Rose went on to fight at Quatre Bras and Waterloo where he was wounded for a second time in his career – this time with a severe gunshot wound to his right arm. After recovering, he resumed his Army career and was eventually discharged with 27 years of service in 1837. He had attained the rank of Sergeant, which gave him a pension of 23 pence per day.

Black veterans of Nelson’s Navy

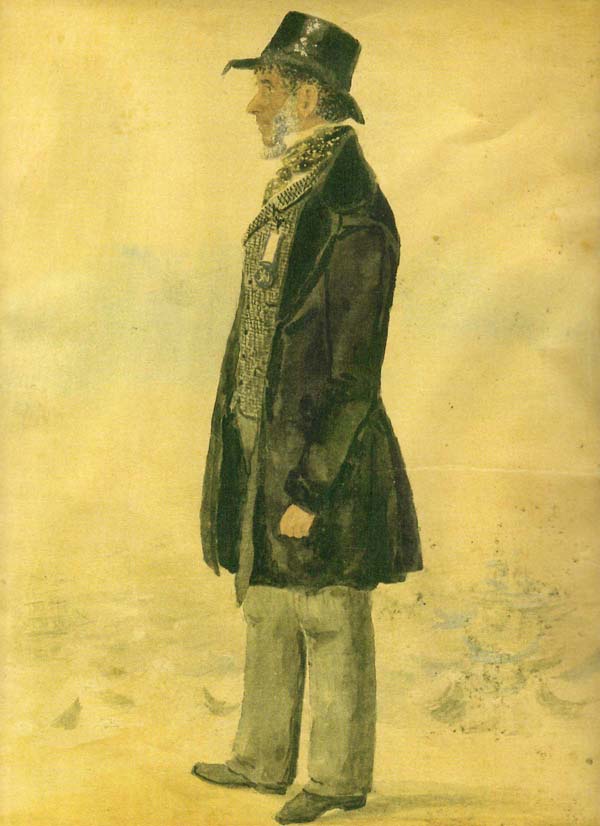

John Simmonds, a veteran of the Battle of Trafalgar and Black Greenwich Pensioner, (c.1784-1858), Courtesy of the family of John Simmonds.

The stories of Black veterans of the period is picked up by the Old Royal Naval College whose exhibition, Black Greenwich Pensioners, tells the story of the Seamen’s Hospital during the Georgian and Victorian periods and the spectrum of Black Royal Navy personnel living there as Greenwich pensioners.

These men ran the full gamut of backgrounds – from people like John Thomas who had run away from enslavement in Barbados to join the Royal Navy, to people like Richard Baker and John Simmonds (above) who were both Trafalgar veterans.

Intriguingly it was the Royal Navy that provided the catalyst for Black radicalism in the period and out of this milieu came the first generation of Black writers in English; men like Briton Hammon, the author of the first slave narrative who was at the seaman’s hospital in 1759, and the writer and abolitionist Olaudah Equiano who had also been to sea with the Royal Navy.

Phillis Wheatley, poet

Phillis Wheatley, Poems on various subjects, religious and moral. Image courtesy of the British Library. Shelfmark: 992.a.34.

The first African Amercian woman to publish a book of poetry was Phillis Wheatley, an enslaved woman whose Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral was published in 1773, the year in which she was freed from slavery.

Her personal circumstances did not improve with the change in status, and although her book made her one of the most famous African women of her time, she died in poverty aged 31. Her writing has however endured and although some scholars say her poems fail to address her own position as an enslaved person, today she is a key figure in African American literature and history.

As well as celebrating her book of poems, we also feature her in Age of Revolution’s Top Trumps which showcase the diverse history, people and ideas of the Age of Revolution through 30 revolutionary historical figures.

Chartist William Cuffay

William Cuffay, the son of a former enslaved African, was a leading figure in the Chartist movement, the first mass popular political movement in Britain.

Born on a merchant ship in the West Indies in 1788, his family later settled in Chatham, Kent where Cuffay became a journeyman tailor. After losing his livelihood following a tailor’s strike, he was drawn to the Chartist movement.

Rising to become one of their most militant leaders, Cuffay was eventually arrested in 1848, tried on the evidence of a government spy and transported to Tasmania for his role in an attempted uprising against the government. As well as featuring his ‘Chartist portrait’ we also feature Cuffay in the Age of Revolution Top Trumps series.

See also the Guildhall Museum in Rochester’s film about the remarkable Cuffay.

Jean-Jaques Dessalines

Jean-Jacques Dessalines’ colony of birth, St Domingue, was France’s most profitable island. In 1791, he was one of the generals who led a succesful revolutionary uprising against the Island’s plantation owners and the system of slavery.

After the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte threatened the re-introduction of slavery in St Dominigue, Dessalines defeated a French colonial army in 1804, effectively winning the war and establishing an independent nation, which became know as Haiti. Dessalines’ rule of Haiti was however short lived and he was assasinated in 1806.

His bust in the collection of the National Maritime Museum is a fascinating fusion of French military stylings and African sculptural traditions. Dessalines and his former general Toussaint Louverture both feature in the Revolutionary Top Trumps.

Father of Haiti, Toussaint Louverture

Toussaint L’Ouverture, by François Bonneville, after Unknown artist etching and aquatint, early 19th century. © NPG

Now known as the father of Haiti, in 1791 François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture led the first successful uprising of enslaved Africans in Saint-Domingue (Haiti) and although he died in a French prison in 1803, he is generally acknowledged as the architect and leader of the Haitian revolution. In 1804 Haiti became the first independent ‘Black’ republic.

Depictions of Louverture, like this portrait, were commonplace in the period and reflect a fascination and reverence for a towering figure who transformed a slave insurgency into a revolutionary movement.