Soldier’s Story: James Ormsby, from Waterloo to Wilderness

Immediately after the victory at Waterloo in 1815, the battle’s veterans were lauded as national heroes in Britain. By the late 1820s, however, supporting these ageing veterans was straining the government’s budget.

To alleviate these costs, the British government developed a scheme whereby it offered land in the colonies to veterans who agreed to commute their pensions. From 1830 to 1833, over 4,000 veterans accepted the government’s offer and immigrated to the colonies. Unfortunately, the majority of these veterans found destitution and early death when they arrived in the colonies: the task of taming the wilderness was too formidable as many were wounded and maimed from their long years on the battlefield. It is estimated that only one in six of these men were able to settle on their lands. By 1839, it was widely accepted that the immigration scheme was a debacle and the British government restored a reduced pension to those who had participated in it.

The following article recounts the history of Private James Ormsby, a veteran of the Battle of Waterloo who commuted his army pension in return for land in the Canadian wilderness. James and his family faced shocking hardships: an endless sea of trees to be felled, unbearable isolation, and miserable winters. Nevertheless, the Ormsby family endured and was ultimately successful in transforming their land into a prosperous farm.

Shoemaker to soldier

Born around 1790 in St John’s Parish in County Sligo, Ireland, James Ormsby was trained as a cordwainer (shoemaker).[1] Although I have not been able to identify James’ parents, I suspect that James followed his father into this trade. Given James’ trade and his later rank in the army (private), we can conclude that James came from a poor family, unrelated (at least officially) to the wealthy Ormsbys from Counties Sligo and Roscommon who are mentioned in Burke’s Irish Peerage. Perhaps to escape this poverty or to find adventure, James abandoned his sedentary trade and joined the British Army’s 52nd Regiment of Foot at the age of nineteen. James was not the only of his countrymen to do so. At this time, an increasing number of young Irishmen were “accepting the Queen’s shilling” — by 1830, 42.2 percent of the Army’s soldiers were Irish.[2]

If James had joined the British Army looking for adventure, he certainly found it — he had fought in some of the most important battles across Europe. The 52nd Regiment of Foot, in which James fought, was a light infantry regiment, tasked with engaging the enemy in skirmishes away from the front lines. The soldiers were trained to move quickly over difficult terrain, and they fought in smaller groups than the line regiments. James would serve in this capacity for three years in the Peninsular War, where British, Spanish and Portuguese allies fought against an invasion of Napoleon’s French troops. Following the Peninsular War, the 52nd was stationed for several years in Flanders and France and fought in the battle of Waterloo. James Ormsby was awarded a medal for his service at this battle. For five years, James’ military career also took him, perhaps fatefully, to the British Colonies of North America. The 52nd Regiment of Foot was stationed in Atlantic Canada from 1823 to 1831.[3]

In 1820 in Northampton, England, James had married Elizabeth Franklin, an Englishwoman.[4] To do so, James would have first required the permission of his commanding officer. The Army discouraged marriage for its enlisted men, fearing that family life was incompatible with the demands of the job.[5] Indeed, by marrying James, Elizabeth was condemning herself to a life of extreme hardship. The wives received no official help from the government and they were often left to support themselves and their children for years as their husbands were stationed abroad. A small number of wives and families (six out of a company of one hundred men) were allowed to accompany their husbands abroad. These families were chosen by lottery. James and Elizabeth were lucky — Elizabeth was one of the six wives in his company chosen to accompany the 52nd Regiment to Atlantic Canada.

Elizabeth Ormsby arrived in her new home a new mother. George Ormsby had been born in Ireland in 1822. A second child (Jane) was added to the family in 1824. Two other children, Andrew and Elizabeth, were also likely born during this time in the colony. The growing Ormsby family would have been expected to fit themselves quietly into the garrison life. Elizabeth and her children would have lived in the garrison building alongside the soldiers. No additional quarters or sleeping berths were allotted to the families: married couples had only the privacy of a blanket and children of the soldiers would often sleep in the beds of soldiers who were on duty. To supplement James’ pay, Elizabeth would have likely spent her days doing laundry for the soldiers in addition to caring for her children.[6]

By 1830, James had served for over twenty-two years as a private, with a short year-long stint as a corporal. Life on the battlefields and in a colonial outpost had taken its toll. James was suffering from multiple health problems: dysphonia (a disorder of the voice), rheumation (presumably rheumatoid arthritis), and a wound in the left groin that had been inflicted during the 1813 Battle of Nivelle in France. In July 1830, he was honourably discharged from the army by reason of disability. In September 1830, he was accepted as an outpatient of London’s Chelsea Hospital, a military hospice had been created in the 17th century to support the nation’s convalescent soldiers. The Hospital would administer James’ pension to him for the rest of his life.[7]

Soldier to pioneer

At the time that James Ormsby retired from the army, the British government had been struggling to meet its obligations to its military pensioners, in particular the 36,000 outpatients of the Chelsea Hospital.[8] In order to alleviate the growing financial burden of their care, the Chelsea Pensioners — as they were known — were offered the opportunity to commute their pensions for passage to and tracts of land in the colonies. James was one of the fifteen hundred British soldiers who accepted this deal and who travelled to Upper Canada to settle in the wilderness.[9]

An 1830 memorandum to the pensioners outlined the terms of the deal. The former soldiers, it was decided, would be required to commute their pensions for a lump sum payment (about four years of pension) and a grant of land of one hundred or two hundred acres depending on the soldier’s rank. To be accepted for this program, the soldier would have to show, with a letter from their home parish, that they and their family members were in good health, and that they had enough money to support themselves for one year in the colony. Once the soldier had booked passage on a boat to the colony, they would receive part of their lump sum payment. The second half of the payment would be given when the family arrived abroad. Should the soldiers decide to accept the pension deal, they would forfeit any right to further support from the British Government.[10]

For the government, the advantages of this program were clear. The government would be able to weed out its military pension rolls at the same time as beefing up the population of sparsely settled, but strategically important land. On the surface, it also seemed like a good deal for the retired soldiers. Like James Ormsby, many of these soldiers had come from impoverished families who had no hope of ever owning their own land or rising above the working class. The four thousand pensioners who accepted the commutation deal undoubtedly felt that this was their opportunity to improve their family’s standing. However, most of these pensioners (47%) were between the ages of forty and fifty years old and forty percent of them had served between fifteen and twenty-six years in the army. By some estimates, almost half of these men had lost limbs in battle.[11] These men were not necessarily those would be best suited to life in the backwoods of Canada. Indeed, it would become quickly obvious that the government’s strategy to thin its pension rolls would result in the destitution and death of many of the Chelsea pensioners who emigrated to the colonies.

Ships carrying the pensioners began to arrive in Quebec City in 1831. On one journey across the Atlantic aboard lumber freighters, cholera spread among the pensioners and their families. According to family history, James and Elizabeth’s daughter Elizabeth (likely born in 1826) died en route to Canada — she had perhaps succumbed to this epidemic.[12] When the ships docked in Quebec City, over fifty men had died. Moreover, as the ships containing the payment instructions were routed through Halifax and typically arrived six to eight weeks after the ships carrying the pensioners; the authorities could not pay out the second half of the lump sum due to the pensioners and many were stuck in Quebec City. Cholera spread quickly. When the payment did arrive, it fueled a drunken binge in which many of their soldiers spent their payouts in the taverns of the Lower Town of Quebec City.[13] Lord Aylmer, Governor of the colony, realized that the commutation plan would create “paupers of the worst description.” He predicted that only three of five would succeed in establishing themselves in Canada.[14] This was an optimistic appraisal of the situation.

James Ormsby was, either through fortune or hard work, one of the few Chelsea Pensioners who survived in Upper Canada. According to government estimates, only one in six of the pensioners managed to endure life in the colonial wilderness.[15] The remainder either died, unable to handle the physical hardship of life in the bush, or ended up destitute in the streets of the larger centres like Toronto or Montreal. Many never even attempted to settle their lands — after their arrival in Canada they had quickly ascertained the likelihood of their success in the wilderness.

James and Elizabeth Ormsby, however, did not seem to hesitate in fulfilling their settlement duties. They arrived in “Muddy Little York” (now “Smoggy Big Toronto”) on 28 June 1831. Presumably, they had travelled from Quebec City by steamer to Montreal, and from Montreal to Prescott by stagecoach or barge. From Prescott to York, the Ormsby family travelled aboard the steamboat Queenston, a vessel that made a weekly circuit down Lake Ontario to the entrance of the Niagara River.[16] In the early 1830s, York deserved the both the monikers “little” and “muddy.” By 1833, the “ill-built town on low land” could only boast a population of 8,500.[17] Samuel Thompson, who travelled through the town two years after the Ormsbys, describes a rough colonial outpost where the mud and the taverns far outnumbered the few signs of civilization, i.e., brick buildings, churches and gaols. According to Thompson, “So well did the town merit its muddy soubriquet, that in crossing Church street near St. James’s Church, boots were drawn off the feet by the tough clay soil; and to reach our tavern on Market lane (now Colborne street), we had to hop from stone to stone placed loosely on the roadside.” The main attraction for Thompson, and likely for the Ormsby family, was the Emigrant Office, where they would receive information about their land and in some instances, the location ticket which would specify the township in which they would settle.

At York, the Ormsby family was admitted to the Emigrant’s Asylum.[18] The Asylum, which was managed by the Society for the Relief of the Sick and the Destitute, provided accommodation and provisions for “deserving emigrants”[19] about whom the charity workers would record judgments in their registers such as “A Very Dirty People”, or “Well behaved and particularly sensitive to cleanliness and safety of [apartment]”. During their eight days in the Asylum, the Ormsby family would stay in the “brick house,” perhaps one of the government buildings described by Anna Jameson in 1838 as built from “staring red brick, in the most tasteless, vulgar style possible.”[20] Here, the family would receive five pounds of beef and thirty pounds of flour before they continued on their journey to Simcoe County.

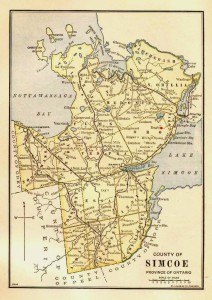

Figure 2: Map of Ontario showing Toronto and Simcoe County.

The red dot shows the location of the Ormsby farm. Image from Wikicommons (GNU license)

On 6 July 1831, the family began their journey north, likely travelling by stagecoach on what is now Yonge Street. At Holland Landing, they would travel by boat up the Holland River — “a mere muddy ditch, swarming with huge bullfrogs and black snakes”[21] — and then across Lake Simcoe to Hodge’s Landing, a town which is now known as Hawkestone.[22] In Hawkestone, the Ormsbys would have perhaps overnighted in a group of shanties that Wellesley Richie, the Government Land Agent, had erected to accommodate the influx of settlers who arrived in Oro during the summer of 1831. Hawkestone lay directly south of the lot which the Ormsbys were assigned and a trail (perhaps created by the Aboriginal inhabitants of the land) led north to what is now the east-west road which passes through the hamlet of Rugby. If they were lucky, the Ormsbys may have found a team of oxen to help them carry their load north. If not, James, Elizabeth, and their three children carried all of their worldly possessions over the six kilometers to their new home.

The Ormsby family took possession of their land on the east half of Lot 14, Concession 12 in Oro Township on 10 July 1831.[23] At that time, Simcoe County was a vast forest that stretched from Lake Simcoe to Lake Huron. Oro Township was, for the most part, unsettled. Whimsically named after the African village “Rio del Oro”, the government first intended the township to be the base for a colony of black families.[24] Attempts were made to start a settlement on Wilberforce Street in Oro Township in 1819. Twenty-three black men, some of whom had fought for the British in the War of 1812, had been granted land in Oro by 1826. The settlement peaked at a population of about one hundred by 1860, but had disappeared from Oro by 1901.[25]

Other white European settlers had arrived in the area in 1819 — these settlers were concentrated along the Penetanguishene Road, which formed the western boundary of the township. A group of half-pay officers, seduced by the idea of lakeshore property, had taken large plots of land along Lake Simcoe in the late 1820s. Sir John Colbourne, Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, had encouraged this influx of military men to the area north of Lake Simcoe. The colonial government felt that Upper Canada might be vulnerable to an American attack through Georgian Bay and therefore encouraged the settlement of military men and their families in this area. For this reason, several Chelsea Pensioners like James Ormsby were assigned land in Oro and in the neighbouring township of Medonte.

Pioneer to farmer

From what little I know of her life in Canada, Elizabeth Ormsby cuts a figure of a hardy pioneer woman. While her time in Europe and in the colonial garrisons was undoubtedly physically difficult, it was nothing in comparison to her life as a settler in Upper Canada. Elizabeth certainly seems to have been capable of handling difficult emergencies on her own. Shortly after the family’s arrival in Oro in 1831, it was Elizabeth who brought a group of sick emigrants back to York. I’m not sure how she would have managed this trip as it would have involved travel over unbroken wilderness, a boat ride, and a journey down Yonge Street with unhelpful passengers. This journey was significant enough that it warranted a payment of ten shillings by the Emigrant Agent.[26] It was Elizabeth again who stepped to the plate when the young colony was unsettled by a rebellion in 1837. James joined the Simcoe County militia to fight against William Lyon McKenzie and his rebels in York (Toronto). The Simcoe County militia wintered in York that year, leaving their wives and children to fend for themselves against wildlife and the potential anger and retribution of Aboriginal groups who were being forced out of their ancestral lands around Lake Simcoe and who were travelling north.[27]

There would have been no limit to the adverse circumstances that Elizabeth and James faced when they arrived in Oro Township in 1831. At that time, the Ormsbys’ one hundred acre lot would have been entirely wooded — its boundaries marked by small white blazes cut into single trees difficult to find in the sea of the forest. To meet their settlement agreement and to be granted the title to the land, the Ormsby family were required to live on their lot, build a house, clear half of the road in front of their lot, and to clear and fence ten acres next to the road — all within the first eighteen months of their arrival.[28] Perhaps because of his army experience in North America, James Ormsby seems to have anticipated the difficulty of fulfilling these conditions. According to Kith n’ Kin, a history of Oro Township, James had been entitled to four hundred acres of land, but he had only accepted one hundred.[29] This was a shrewd decision and one that perhaps saved the Ormsby family from the fate of many of the other fifteen hundred Chelsea Pensioners who had come to Upper Canada.

Still, a plot of hundred acres of hardwood could have thousands of trees. Trees — beech, maple, elm, ash, cherry and pine — covered all of Simcoe County from Lake Simcoe to Lake Huron. For the first summer — no, the first decade — the entire family, including Elizabeth and any child old enough to wield an axe, would have spent every day of their lives chopping down trees. These trees were no saplings. Early settlers reported oak trees eighty feet tall with a twelve-foot circumference at the base.[30] As Anna Jameson suggests, “a Canadian settler hates a tree, regards it as his natural enemy, as something to be destroyed, eradicated, annihilated by all and any means.”[31]

Immediately upon arrival, the family would have had to clear enough trees to build a shanty — a one-room log house that would provide shelter for the family over the winter. Then the family would continue to clear trees, as many as possible, in order to make room to plant a crop, likely wheat, for the following summer. Given the lack of infrastructure, it was impossible to sell or remove logs from the property and the trees were duly burned, with the slight redemption that the potash would fertilize the ground for future crops. The trees did not give up the land easily, however, and the Ormsbys and the other settlers would have to wait seven years before the stumps were rotten enough to be pulled from the ground. Only once these stumps were removed could the family use farm implements to plow the land.

Initially, any provisions that the Ormsbys had needed were likely carried north by foot, probably procured in one of the small settlements along the shores of Lake Simcoe or farther afield in York. Given their lack of means and crops, the Ormsbys’ diet would have been limited to cakes of flour, salted meat (likely pork), any game or fowl which could be killed, and a tea/coffee substitute brewed from indigenous plants.

These trips for provisions would be among the only opportunities for social contact in Oro Township. The Ormsbys’ land was twenty kilometers from the area’s main artery: Penetanguishene Road. Although another road was cut out of the forest between Kempenfelt Bay and Shanty Bay by 1833, it wasn’t until 1835 that the first postal service arrived in the township.[32] Even once the roads had been cleared, Oro Township remained isolated. One early pioneer recounted a story about a young woman who was walking to visit neighbours several miles away. Ahead of her, she saw a man on a horse. To see another human being on this road was such an unusual occurrence that she picked up the horse’s dropping as proof of what she had seen.[33]

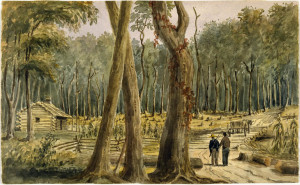

Figure 4: An Ontario bush farm in 1838. The tree stumps have not yet rotted enough to be removed. Source: Library and Archives Canada.

James and Elizabeth Ormsby likely endured a decade or more of these isolating and backbreaking conditions. But they did endure. The piece of wilderness that they had been given was, ultimately, a productive farm. In 1861, thirty years after their arrival in the wilderness, the Ormsby farm produced one hundred and fifty-five bushels of spring wheat, eighty bushels of peas, one hundred and seventy bushels of oats, and two hundred and fifty bushels of potatoes. The two Ormsby children who had survived to adulthood lived on the property with their families — George Billings Ormsby and his family lived in a new frame house; James Jr. and his small family lived in a log cabin, perhaps one of the original buildings that had been erected by James and Elizabeth.[34]

As proof of their hardiness, James and Elizabeth both lived past their eightieth year. James died in 1873 and Elizabeth some time after that date. Direct descendants of their son George Billings Ormsby lived and farmed the original Ormsby property well into the 1970s, almost 150 years after the arrival of their pioneering ancestors.[35] James Ormsby Jr. tired of the farming life and opened a hotel in nearby Washago by 1871.[36] His sons would gravitate to the larger urban centres and entrepreneurial lives — they lived the promising future that their grandparents had hoped for.

__________________________________________

Footnotes:

[1] Royal Hospital Chelsea, “Soldiers’ Service Documents (1760-1854),” photocopy, UK National Archives, entry for James Ormsby, 52nd Regiment of Foot; catalogue reference WO97/658.

[2] David G. Chandler, and I. F. W. Beckett, The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 169.

[3] Royal Hospital Chelsea, “Soldiers’ Service Documents (1760-1854),” photocopy, UK National Archives, entry for James Ormsby, 52nd Regiment of Foot; catalogue reference WO97/658.

[4] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “International Genealogical Index,” database, Family Search (http://www.familysearch.org : accessed 20 Dec 2009), entry for James Ormsby and Elizabeth Franklin, married 05 Nov 1820; citing parish records from Northampton, Northampton, England

[5] David G. Chandler, and I. F. W. Beckett, The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army, 172.

[6] David G. Chandler, and I. F. W. Beckett, The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army, 172.

[7] Royal Hospital Chelsea, “Soldiers’ Service Documents (1760-1854),” photocopy, UK National Archives, entry for James Ormsby, 52nd Regiment of Foot; catalogue reference WO97/658.

[8] Doris Bourrie, “The Chelsea Pensioners – Victims of Bureaucracy?” Families 47, no. 2 (2008), 6.

[9] Barbara B. Aitken, “Searching Chelsea Pensioners in Upper Canada and Great Britian. Part 1 – Sources,” Families 23, no. 3 (1984): 114-27.

[10] Great Britian War Office, Chelsea Pensioners : Copies of Despatches and Correspondence Relative to Chelsea Pensioners in Upper and Lower Canada., Parliamentary Papers / Great Britain. Parliament (1837-1841). House of Commons ; 248, 1839 (London, UK: Great Britian War Office, 1839), 7.

[11] Mark Bourrie, “War Veterans in the Wilderness,” Legion Magazine (2002).

[12] Joanna McEwen, Kith ‘N Kin: Reminiscenses, Biographies, Genealogies, Photographs (Oro Township, ON: The Corporation of the Township of Oro, 1978), 287.

[13] Mark Bourrie, “War Veterans in the Wilderness.”

[14] Great Britian War Office, Chelsea Pensioners : Copies of Despatches and Correspondence Relative to Chelsea Pensioners in Upper and Lower Canada, 12.

[15] Great Britian War Office, Chelsea Pensioners : Copies of Despatches and Correspondence Relative to Chelsea Pensioners in Upper and Lower Canada, 43.

[16] Ivan S. Brookes, “Hamilton Harbour 1826-1901,” http://www.halinet.on.ca/greatlakes/documents/brookes/default.asp?ID=52 (accessed 06 January, 2010).

[17] Anna Jameson, Winter Studies and Summer Rambles in Canada (New-York: Wiley and Putnam, 1839), 39.

[18] Michael Harrison & Dorothy Martin, editors, Records of the Society for the Relief of the Sick and Destitute (1814-1847) (Toronto, Ontario: Toronto Branch Genealogical Society, 2002), 26.

[19] J. K. Johnson, and Bruce G. Wilson, Historical Essays on Upper Canada : New Perspectives (Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1989), 310.

[20] Anna Jameson, Winter Studies and Summer Rambles in Canada, 7.

[21] Samuel Thompson, Reminiscences of a Canadian Pioneer for the Last Fifty Years : An Autobiography (Toronto: Hunter, Rose, 1884), 41.

[22] Andrew F. Hunter, A History of Simcoe County (Barrie, Ont.: County Council, 1909), 142.

[23] Petition of James Ormsby,” 30 May 1835, “Upper Canada Land Book,” Petition O19/7.

[24] Andrew F. Hunter, A History of Simcoe County, 134.

[25] Oro Historical Committee, The Story of Oro (Oro Station, Ontario: Township of Oro, Historical Committee, 1987), 7.

[26] Elizabeth Ormsby, Carriage of Sick Emigrants from Oro to York, Disbursements made by Mr. F.T. Billings at York, 1831, Emigration Accounts, No. 45; Early Canadiana Online (http://www.canadiana.org).

[27] Samuel Thompson, Reminiscences of a Canadian Pioneer for the Last Fifty Years : An Autobiography.

[28] Joanna McEwen, Kith ‘N Kin: Reminiscences, Biographies, Genealogies, Photographs.

[29] Joanna McEwen, Kith ‘N Kin: Reminiscences, Biographies, Genealogies, Photographs, 286. I think that this may have been an exaggeration on James Ormsby’s part as only officers were entitled to that amount of land. He may, however, have been offered 200 acres.

[30] Samuel Thompson, Reminiscences of a Canadian Pioneer for the Last Fifty Years : An Autobiography, 99.

[31] Anna Jameson, Winter Studies and Summer Rambles in Canada, 72.

[32] Oro Historical Committee, The Story of Oro, 101.

[33] Oro Historical Committee, The Story of Oro, 102.

[34] 1861 Canada census, Oro Township, Simcoe County, Ontario, agricultural schedule, p. 1, lines 22 and 23, George Ormsby and James Ormsby, roll C-1073.

[35] Joanna McEwen, Kith ‘N Kin: Reminiscenses, Biographies, Genealogies, Photographs, 287.

[36] 1871 Canada census, Washago, Simcoe County, Ontario, population schedule, p. 21, district: Simcoe North (42); sub-district: Orillia (K-02), family 70, James Ormsby.