The Duke of Wellington’s Desk?

In August 2006 I arrived at the headquarters of London District in Horse Guards on the well known thoroughfare of Whitehall in London.

This very impressive and iconic building has been part of London’s rich history since the days of Henry VIII and, as I was to discover very early on, it has been subject to many descriptions and stories which and have been passed down only by word of mouth or in some haphazardly written documents held on the main computer system.

This very much applies to the pictures, fixtures and furniture which adorn some very ornately decorated offices in the central area of the building.Shortly after taking up my post I assisted in the annual event known as “Open House London” where the general public are permitted access to hitherto closed buildings in and around London for one weekend per year. I joined a team of officers and learned civil servants giving talks to visiting groups which principally concerned the two main rooms known as the Wellington Conference Room and Office of the Major-General. These rooms overlook the small courtyard to the east of Horse Guards and opening onto Whitehall and Horse Guards parade to the west respectively.

After the event I took it upon myself to investigate the origin of the “talks” only to discover they were very anecdotal and subject to liberal embellishment and thus much of the true history of many of the items in the rooms had now been lost. This was none more so than the history and provenance of the most iconic piece of furniture in the office of the Major-General the table known to all as “Wellington’s Desk”. Stories ran from the desk being made for the Duke of Wellington and commissioned by his soldiers to it being commissioned in the year 1767 for the Duke a full two years before his birth.

I therefore began some earnest research and came to a more acceptable history of the table until in 2011 when I was fortunate enough to make the acquaintance of the TV auctioneer and antiques expert Tom Keane – best known for Cash in the Attic and Housegift. Tom has a speciality in antique furniture and I invited him to Horse Guards to view Wellington’s Desk and carry out some further research. The results were very revealing and whilst there is still no certainty as to the maker of the desk we do now have a more in depth history.

It is known that the desk itself has been in the office of the Major-General since the late 1700s when the room was once known as the Courts Martial Room and then the Levee Room. It became the sole office of the Commander in Chief of the British Army sometime in the early 19th century. The desk itself was commissioned and purchased by Frederick Duke of York the second son of King George III. The Duke of York became Commander in Chief in 1795 in succession to Lord Amhearst and remained in office until his death in 1827 (apart from a short time from March 1809 to May 1811). The Duke of Wellington was then given the post of Commander in Chief from 1827 but resigned to become Prime Minister from 1828 to 1830 and follow a political path. In 1842 he again became Commander in Chief and remained in office until his death in 1952. On his death the desk was removed to the Duke’s London home Apsley House but in the early 1900s it was once again placed at Horse Guards by the Duke of Connaught and it has been the working desk of the Major General since this time. It was at this time that the term “Wellington’s Desk” became the de facto name of the table. The office of the Commander in Chief has moved several times since the early 20th century, from Pall Mall to the Old War Office building and then to the Ministry of Defence Main Building but the desk has remained in use by the Commanders of the units occupying Horse Guards. It has been in the office of the Commander London District and the Major-General Commanding the Household Division for many years.

Several views of the desk have been expressed over the years from the type of wood it is made of, what its purpose was and what was its position in the room.

The research of Tom Keane has been very fruitful and we can now assign the desk a more acceptable provenance.

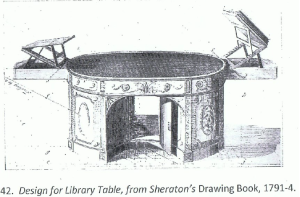

The original drawings for Wellington’s desk appear in Thomas Sheraton’s book The Cabinet Maker & Upholsterers Book dated 1791. Some documentation written by Sheraton also states that “the oval library table is intended for a gentleman to write on or stand at or sit and read at” and very importantly he goes on the say “it has already been executed by the Duke of York” So we know the original purchaser and can date the desk to about 1788-1790.

Thomas Sheraton was in his early years a journeyman cabinet maker but little is known about his family for the first forty years of his life. He worked in Stockton and he was competent draughtsman although we do not have evidence of any formal education he undertook. Sheraton came to London in about 1790 and supported himself and his young family as an author. He is recorded as living in several addresses in Grosvenor Square (1791-1795), Wardour Street (1795) and later for some years at No 8 Broad Street Golden Square. It is probable that he made furniture in his later years but had no active interests in the hundreds of cabinet making workshops in London and had no workshop of his own.

It is nearly impossible to identify the maker of Wellington’s desk. However, the quality of the desk suggests a cabinet maker of the first rank and the name Shearer keeps cropping up in the research. English craftsmen of this period very rarely signed their work or stamped their pieces, unlike the French where it was law from as early as 1742. Leading cabinet makers were also unwilling to produce published designs unless to special order.

Sheraton’s drawings for Wellington’s desk show telescopic architects easels fitted to the interiors of each of the end drawers and on inspection there are some scars to these interiors suggesting they were removed, probably early in the 19th Century.

There are also some differences to the outer carcass decoration, the original purchaser probably thought it too fussy and simply liked a plainer design.

In summary we can conclude that the original purchaser who commissioned the desk was the Duke of York, between 1788-1790. It was of a Thomas Sheraton published design by an as yet unidentified cabinet maker but possibly Shearer.

A full description can therefore now be ascribed to the desk in the GOCs office at Horse Guards as follows:

“A Sheraton period and design flame mahogany and satinwood banded library table in oval form, the green tooled leather writing surface above and arrangement of drawers with bow and inverted oval panelled cupboards below, supported in plinth bases.”

It is hoped then that this narrative on the history and provenance of Wellington’s Desk can be added to the talks given to many visitors to Horse Guards. During the Open House in September from 2007 – 2012 I was privileged to give these talks at each weekend to some 2,000 visitors. Other groups who came along and received the talks were the Royal Academy of Arts, several military officers and senior non-commissioned officer courses and other specialist groups. In 2010 I gave to talk to the senior NATO commanders and officers from the Permanent Joint Headquarters and in early 2011 I was privileged to present the history to the Commander in Chief of the Afghanistan National Army accompanied by the British Chief of the Defence Staff.

Wellington’s Desk has a special place at the very heart of Horse Guards, in the history of London and in the origins of the British Army and it deserves to have its true provenance known . I hope my research with assistance from the very respected and knowledgeable antiques expert Tom Keane has gone a great deal further in establishing this provenance.

Ian Mattison

Major RE (Retd)

Horse Guards 2006-2011

The plates are taken from the copy page number 561 of The Shorter Dictionary of Furniture, published in 1964