Walking the Battlefield of Waterloo

When walking a certain battle site in Belgium you will notice that something monumental is absent.

On the 18th June 1815, over rolling countryside between two ridges 11 miles south of Brussels, the entire course of European history changed. On the Battlefield at Waterloo, the tactical skill and staying power of The Duke of Wellington opposed Napoleon Bonaparte’s brilliance, in an effort to decide the providence of Europe.

The culmination of one of the greatest gambles in military history, spectacular by any criterion, saw the rout of an Empire and the complete eclipse of a charismatic Corsican and greatest soldier of modern time. It happened on one of the smallest battlefields in Europe and all on a Sunday afternoon.

If you have never been to Waterloo, or indeed to any battlefield before, then I trust this article might entice you to do so. These snippets from 1815 are in no chronological order. The phased sequence of the Waterloo battle is omitted and left for discovery.

Battlefield Touring

Battlefields have always provided intrigue for those interested in military history. Whether it be a fascination to relive history established in childhood, a chance to enhance a learning experience or perhaps to pursue a relative’s footsteps, reasons for touring are normally unique to the individual concerned. Re-enactors naturally walk battle sites, thereby enriching their understanding of their chosen pastime. Likewise, war gamers venture out to battlegrounds, if only to study the terrain and thus site their board game model army better, thereby enhancing their chances of victory the next time the dice is rolled. Such are typical reasons that draw you into a never ending fascination for touring.

Battlefields

Three ingredients are essential to all such quests into history. The initial one is the terrain, the very ground ‘where it happened’. Where ‘the Lancashire Fusiliers hid in the sunken road prior to their attack on the 1st July 1916, the first day of the Somme’ or where ‘that tiny gap, barely 350 yards wide, where Henry did his bit at Agincourt’ are examples of such intriguing locations that entice you to tour. Whether it is to Omaha Beach, Ramillies or Belle Isle, the excitement and anticipation of seeing those places for the first time is, for most visitors, a memorable and unique experience. Comments like ‘So that’s where the windmill was’ or ‘my… that right flank is far bigger than I had ever imagined’ will no doubt reminisce with some. The ground is the key. It does not lie. Whilst history is manmade the terrain you see, primarily is not. The ground can dispel the myths and prove the truths.

Viewing the ground, coupled with the second and absolutely fundamental factor necessary for successful battlefield touring, provides enjoyment, intrigue and understanding. I refer of course to the need for a story teller. The guide who creates the atmosphere generates the interest. By relating to history they believe is true, they can, with appropriate ‘cordite’ and emotion, bring you there. Hence the saying, ‘a tour is as only as good as the guide who leads it’. It is the guide who is responsible for firing the best aid you have …… your imagination. So important is this third factor, and in conjunction with the former, it helps to, as the phrase has often been coined, ‘bring history to life’. This Article refers by numbers to locations and incidents on the field at Waterloo.

The Wellington Museum

Ideally, a weekend stay enables you to visit most of the museums and places of interest. Additionally the hotels, inns and restaurants in Waterloo, coupled with the nightlife of Brussels, enhance any tour there, especially for groups. As you approach the town from Brussels along the N5, you pass through the mighty Forest of the Soignes. Most people are unaware that it was along this road, at 6 o’clock on the morning of the 16th June, after one of the most famous Balls in history, that Wellington rode south, eventually to meet Blucher at the windmill at Bussy. Later that day, while Napoleon smashed the Prussians in his last victory at Ligny, Wellington would take on Ney and the Left Wing of Napoleon’s Armee du Nord amid the scorching rye at Quatre Bras.

The first place to visit in Waterloo is the Wellington Museum, which was the Duke’s Headquarters during the battle. In those days battles were named after the location of the Headquarters of the victor. The museum, with its many artifacts, paintings and chronological displays gives you an overview as to what happened there in June 1815. Wellington’s bedroom still contains his bed where his ADC Gordon died. Many other officers on Wellington’s Staff suffered a similar fate. It is said that de Lancey, his Quartermaster General, died from a cannon ball that never touched him! It passed so close to his backbone that the following vacuum ripped the muscles from his upper spine, destroying his respiratory function. The Museum extension presents an easy to follow brief as to the situation in Europe in 1815 and an insight as to what was taking place at the all important Congress of Vienna. This ‘must visit location’ will interest you for at least an hour, and more if lady visitors get their way! Four kilometers south of Waterloo, the gigantic Lion Mound looms into view at Mont St Jean. The very second you see it an inquisitive sense of exhilaration engulfs you as you are aware it marks the most famous and talked about battlefield in history.

Your first point of intrigue must be the miniature Albert Hall shaped building which contains the largest mural in Europe. It feeds the imagination far better that any guide or book on the subject. Some 12 meters high, and 110 meters in circumference, the Panorama, painted by Louis Doumouline and friends at the turn of the last century, breathtakingly portrays the scene of battle. It depicts the French cavalry charges led by Marshal Ney and Wellington’s troops are in squares ‘prepared to meet cavalry’. All the major players feature amid the smoke, noise and chaos of battle. This unique artistic extravaganza is able to give Waterloo first timers a more vivid understanding of Napoleonic warfare and of that bloody day. Despite slight water damage being repaired by the local Walloon authorities, the Panorama is perhaps the most exciting image of Napoleonic battle actuality you will ever see.

During a steady 3 minute climb to the Lion (2), perhaps be mindful that below this point, almost 200 years ago, Allied infantry squares prepared to meet the shock of French cavalry action, and the desperation of Wellington’s crisis at 6pm on that hottest of days. The number of steps you climb to the summit of this monument is an aide memoir that in 1815 there were some 226 horses in a Royal Horse Artillery battery. You can now catch your breath some 140 feet above the battlefield where spectators are privileged, weather permitting, to an awe-inspiring panoramic view, an advantage not afforded to Wellington or Napoleon. Many readers will have read eyewitness accounts of the 18th June 1815. However, the one aspect of truth, the ultimate authority, is now there before your very eyes – An historical vista of European heritage so important – the battleground itself!

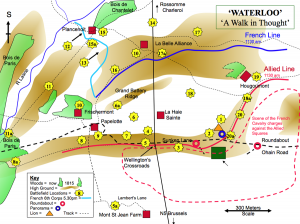

Car parks, Roundabouts and an Underground Museum

From the summit of the Lion Mound (1) look south towards where the French were positioned on the ridge some 900 yards distant(16 + Dark Blue Line). The valley area in front (18) is where the battle movement largely took place. With rudimentary knowledge of the battle you soon realise that the real area of conflict, with the exception of the combat that took place at Hougoumont and Plancenoit, is on the reverse northern slopes of the Mont St Jean ridge and is actually beneath and behind you. It is here that the carnage of the French cavalry charges, against all those Allied battalions in square, ensued for well over 2 hours. When Hake’s Prussians pushed south out of the Bois de Paris (11) at approximately 5pm, they observed the charges ongoing at a pace. It is on the Ohain road, within 200 meters of the Lion Mound that two roundabouts are to be built to provide access to a large car park behind the ridge. It is in these fields where the Allied infantry waited in silence for the onslaught of Marshal Ney’s heavies that an underground museum will be built in time for the 200th Anniversary of the battle. All buildings on the southern side of the road, less the Mound and the Panorama will be removed.

Sitting on the southern side of the terrace that surrounds the 28-ton Lion (the monument erected to the wounded Prince of Orange), you can look northeast towards the farm at Mont St Jean, which on the day had become a hospital. Alongside it you can pick out the Charleroi road which, cobbled in 1815, saw the constant flow of the deserters and wounded moving northwards to an even bigger hospital in Brussels. This highway, along which the Irish-born Wellington had been unsure whether Napoleon’s main axis would advance, was also the site of the Allied wagon train. It was here that many of the thousands that deserted Wellington on the day plundered from their own provisions.

Now look to the eastern horizon in the direction of Wavre. Although out of sight and 10 miles distant over the now virtually non-existent Bois de Paris, you may wonder what the 3rd Prussian Corps’ Chief of Staff would have been thinking. Others wrote of his teachings of which you might be aware. He was of course the great military theorist; Von Clausewitz.

A scan of the battlefield below and you can locate the French (strength: 72,000 + 246 cannon) and Allied (strength: 68,000 + 156 cannon) dispositions and spy the wood, which now contains the ruins of Chateau Frischermont. You can also see the defile running northwest beyond Hougoumont Farm, which presented dead ground to the Duke and where, as has been proved by metal detection and x-ray photography, the intensity of battle was highest. Your imagination then starts to grip as you become aware of what actually happened on that Sunday in 1815. You can also locate the Grand Battery Ridge (6a) and if the imagination is really keen, you will no doubt sense the cannon thunder and flashes of Napoleon’s 12-pounder ‘Beautiful Daughters’. As reported by the Dover Gazette, these guns were heard on the English South coast seafront that day, across the Channel and some 140 odd miles away. Lambert’s Lane (5a) is also visible where the 27th Foot formed up before they advanced to hold Wellington’s Center at 3pm. On the Monday, Wellington found the Enniskillen’s literally ‘Dead in Square’. Much more than bravery; this was courage …… as the monument at the crossroads that they successfully defended fully testifies to.

Napoleonville

Descending from the Lion Mound into a now busy Napoleonville, a hamlet of tourism, you might be forgiven for getting the impression that the French won at Waterloo. “Why is a Napoleonic victory almost believed and celebrated by tourists from near and far?” is a question frequently asked by visitors to Mont St Jean. The answer is simply that Waterloo is the place where France died. With it also the reputation and power of the greatest military genius of modern time, together with all the French glory that Napoleon’s charisma had created. After his death he was enshrined as a national hero. This lighter side is his legacy and bears witness to his vision and endeavours for France’s pride and prosperity. Even today, French law, judicial, educational, medical, financial, cultural and political structures, the very “Pillars of State”, are of Napoleon’s administrative and economic making; Bonapartists, however, rarely refer to his darker side.

Stroll

Wearing stout shoes, and with hat, map, camera, drinks, sandwiches and foul weather garments in a knapsack, you can start a walking tour. From the Lion, walk east along the line of the sunken road towards Wellington’s crossroads. Halfway there climb up onto the north bank to see what Ompteda’s troops would have been able to see during the battle, (3). Not a lot. Although your view is extensive, despite several buildings on the northwest side of the junction (but only one in 1815) you are not peering through the battle smoke or the tall rye, but more significantly, through the wide area from where all the earth was removed after the battle to build the Lion Mound. Look forward with all that in mind, and it illustrates the care Wellington took to shelter his troops from fire as best he could. This position, like virtually the rest of his defensive line, was mainly sited on the reverse slope. Wellington’s eye for ground was no doubt born from his love of hunting and later enhanced by his military experiences in India and Spain. At Waterloo this “feel for the ground” undoubtedly saved many lives.

South and below the ridge, La Haie Sainte farm was at the centre of the Allied line.

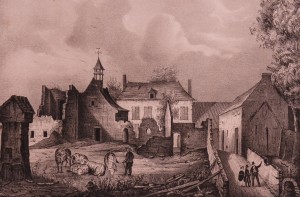

Viewing the farmhouse from the sandpit (4) where two companies of the 95th defended the eastern side of the farm, you are reminded of Ensign Frank who, having to hide under a bed in the attic during the French onslaught, witnessed two of his wounded comrades being bayoneted to death. Also the view of the pigsty roof, from where Baring’s men heaved roof tiles at the invaders, and that of the eastern gate hacked down by Lieutenant Vaux, the tallest sapper in the French army, are virtually as they were in 1815.

Baring’s 450 men of the King’s German Legion had slept in the farm on the night before the battle. They took down the Great Barn doors for firewood unaware that they would have to defend the farm the next day. When the French attacked through the open door, the garrison held the initial assault and during the lull in fighting piled up the enemy dead in the doorway to form a barrier against the next attack. The back door of the main house through which Baring and his remaining 40 men escaped, having run out of ammunition, is also close to the spot where Ompteda was shot from his horse at close range whilst leading the counter attack. Today, and to prevent a multitude of visitors, the “Private – No Entry” signs protect the property for the owners who are descendants from the same family resident in 1815.

Wet Meadow

Waterloo literally means, “Wet meadow”. The condition of the ground on the day was such that shoes and cannon balls simply disappeared by their hundreds into the mud. Two minutes away you can stand east of Wellington’s crossroads on Picton’s Line(5), astride a cobbled road that was merely a boggy lane on the day. If you gaze down into the valley bottom, where Bylandt’s Brigade had bivouacked (6) in the middle of the rain soaked rye on the night before the battle, you are looking at the ground where some of those men, who had gallantly fought at Quatre Bras on the 16th June were to die on the 18th. During the night of 17th many soldiers were trampled by bolting horses, which had been frightened by the numerous lightning strikes that emanated from that prolonged and torrential thunderstorm. The same storm had prevented the French cavalry from enveloping the Allied withdrawal to Mont St Jean. It was on the southern, steep slopes of the ridge (7) that Donzelot’s, and further to the east, Marcognet’s masses had started their climb to the crest. Here they met Wellington’s grape, (actually canister shot, but often referred to at the time as “grape” or “grapeshot”), Picton’s volley and charge, and latterly, the hooves and ‘rough sharpened sabres of the Greys’ of the Union Brigade as they set about the best part of three Divisions of d’Erlon’s French infantry. Amidst the tall, wet rye it must have been a daunting time.

Chance Decision

Continue eastward along Picton’s line to Zieten’s Crossroads (8). Look some 400 yards in the direction of Wavre to Chapel Jacques (8a). It is here that Zieten’s 4,000 Prussians appeared from the wood to descend southwards in an effort to join Blucher who was, by then, well joined in battle with the Imperial Guard in the fight for Plancenoit. The great chance decision at Waterloo was made here, following the disagreement between two Prussian Officers in front of General Ziethen. The fattest Officer in the Prussian army looked on from this spot. The story that unfolded here is amazing and is left for intrigue and another time. Now amble south down a sunken lane towards Papelotte Farm (9). The terrain grows up around you as if you had strolled into parts of Devon. The lower half of the La Haye barn still shows its original grey stonework. Very little is known about the actions of the battle in this area as those under Saxe-Weimar’s command wrote few memoirs. Also Saxe-Weimar’s leadership had been so positive that no Allied assistance had been necessary. With the closeness of the countryside it is easy to imagine how earlier advancing Prussian troops had become involved in fratricide with Saxe-Weimar’s troops. 57,000 Prussians had ‘marched to the sound of the guns’ from Wavre. 28,000 became involved in combat.

Another Duke

Continuing south out of the valley onto a small ridge, you find the wood and the ruins of Chateau Frischermont (10). It was here at about 10.30am on the Sunday that a French patrol drove back Saxe-Weimar’s pickets, heralding the first clash of the day. You can be some 300 years back in time looking down the Chateau’s well as it was also here that the Duke of Marlborough set up his Headquarters in 1705. Two minutes on, after negotiating a hoard of stinging nettles, you stand over the Frischermont ruins, perhaps remembering Marlborough and his ‘glorious victory’ at Ramillies.

In late 1705, it was here that Marlborough had written that if Brussels needed to be defended from the south then the ridge at Mont St Jean was the place to do it.

As Wellington read Marlborough whilst in India, you might possibly understand better the Duke’s reasons for choosing such ground and his subsequent reference to the position of Waterloo by his supposed utterance, “I have kept it in my pocket.” History’s suggestion that Wellington had reconnoitred his defensive ridge at Mont St Jean is further supported by Lady Shelley’s account of her conversation with the Duke of Richmond some years after that most famous Ball. Wellington had asked him at the Ball to see a map of the area. Richmond subsequently ringed with a pencil the thumbnail mark that Wellington had left on the map. The pencil mark circled the ridge at Mont St Jean.

The way of the Prussian

Continuing in an easterly direction, you gain the plateau of the Bois de Paris. It is here that you can visualise Hake’s Prussians pouring out of that wood from your left and North (11a). The wood was so much bigger in 1815. Face south on the highest spot of the track you can find (11). The wooded area of the River Lasne valley is on your left and a remnant of the southern edge of the Bois de Paris to your right. Here you will see, at a thousand yards distant, the spire of Plancenoit village church. In the blazing heat of the battle, Bulow’s 4th Corps (13) drove Lobau’s French reserves back towards the said spire. Pirch’s 2nd Corps mirrored the action on the left a short time later (12).

Five years ago, I stood at this location (11) and wondered why historians had referred to Blucher’s ‘obsession with Plancenoit’ as some sort of leadership failure by distraction. He has been accused of concentrating all his forces towards the village with the assumption that it was his hate for, and required destruction of, the French that was his motivation. After two attacks the Prussians then encircled the village and forced the Young Guard to retire. Back in 1999 at this high point, and by studying the ground, I pondered this entire historical assumption in a manner that a battlefield guide would, as opposed to that of a military historian author.

My imagination endeavoured to relive the situation as seen through the eyes of one of Bulow’s Officers on horseback. Fortuitously, to my left, and saddle high, stood a farmer’s compost heap, onto which I, to my later regret, clambered. Knowing already that his leading Prussians are already outflanking the Grand Battery, through his telescope, one of Major General Hake’s Landwehr Officers would have observed the Plancenoit Spire. What became clear through my binoculars was that the Prussian officer’s eyes would fall not only upon the village of Plancenoit but also, and more importantly, upon Rossomme and the Charleroi road (14). Of course, it was on this road that Napoleon’s administration, support and commissariat were assembled. Thereby, it can be assumed that upon this sight the Prussians glimpsed a winning prize; the chance to surprise and seize the French rear. Only then can one contemplate better the reasons why Prussian cannonballs flew over the French baggage train. Additionally the reason why Blucher’s written orders, via Scharnhorst (the courier), to Zieten as he emerged from Chapel Jacques, had demanded the march of the Prussian 1st Corps to Plancenoit. Yes, on this high spot you view almost the entire battlefield and can even imagine those words of Blucher… ‘forwarts mein kinder’

Battle of La Belle Alliance

Suffering the effects of their 2 day forced march from Liege, Bulow’s men had broken bivouac at Dion-le-Mont at 4am that morning and with little sleep and on empty stomachs had negotiated their Rubicon across the Lasne defile at Ferm de la Kelle in horrendous conditions. Once across this defile they were committed to the “Sound of the Guns” and combat. I have often regarded the events of the 18th June as three distinctly separate but simultaneous battles; Waterloo, Hougoumont, and La Belle Alliance, the last of which contained the equally violent and engrossing combat in and around Plancenoit. Debate perhaps for another time but Blucher did name the battle accordingly as he saw it.

Le Gros Velo is a small restaurant owned by Catherine and Michael on the Plancenoit village green. The cuisine is really quite superb. However, be patient for a Belgium supper, as it may take longer to appear than Zieten’s Corps did to reach Wellington’s right…. but it is well worth waiting for! The peaceful setting below the church contrasts immeasurably with that of 191 years ago when Prussian cannon and sheer hatred for the French had sucked in the vast majority of Napoleon’s reserve. While waiting for supper, walk around the church and graveyard, the focal point in the village where two battalions of the Old Guard saw off thousands of young inexperienced Prussians. If time permits, manage a visit to the nearby Prussian monument (15). It was here that the first 3 Prussian guns deployed to engage the French, west of the village. The monument’s heraldic gold letters testify to the Prussian victory of ‘Belle Alliance’. If you are there on a cloudless mid June evening, move 50 meters north to a small prominent concrete block (15a) and watch the sun’s red ball sink behind the Lion Mound. What a photograph!

Heading towards La Belle Alliance and d’Erlon’s Corps position you cannot fail to notice how easy it must have been for the Grand Battery to fire over the heads of d’Erlon’s advance in echelon. You will appreciate how different the battlefield now seems from the French viewpoint. If you look towards the Lion Mound between Hougoumont and La Haie Sainte, it was here that Marshal Ney(Napoleon’s Field Commander) first led 41 Squadrons of cavalry and then 37 more, all without infantry or artillery support. Peer forward to the line where Foy (Commander French 9th Division) had cried when he saw 5,000 horses, the pride of France’s cavalry, ride to their peril during that almost surreal moment in warfare, so well depicted by Doumouline in the Panorama. Furthermore, from this standpoint it is also quite possible to see why Ney could not see out of the valley, and Napoleon, when 1800 yards further south at Rossomme, could not see into it. Look 800 yards to your left and see the rise of ground (17) where Kellerman (Commander French 3rd Cavalry Corps) had openly argued against Ney’s order. He had done the same at Quatre Bras.

Now follow the route of France’s last effort, that of the Imperial Guard as it attacked with some cavalry, artillery and tirailleur support towards Wellington’s centre. Stand at the spot, just forward and northwest of Belle Alliance, where Napoleon handed over command of the Garde to Ney (17a). At this point be aware what concurrent activity was happening while this column of French imperial prestige started its final attack march. The ‘Battle within the Battle’ at Hougoumont was still raging. After seven attacks by Jerome Bonaparte, the Emperor’s younger brother, who commanded the largest Division on the day, a third of the French infantry had been committed and mostly destroyed. The “Battle behind the Battle” at Plancenoit was now beginning to sway in favour of the Prussians. Elsewhere, Napoleon’s false message of hope of the arrival of Grouchy was beginning to reach his troops; most allied squares had formed into line and a French battery was battering the Dutch and Germans on the north side of the now captured La Haie Sainte farm.

With a battle column of over 550 yards long and with a frontage of 60 veteran Garde, this great spectacle, with bands playing, must have been an awesome sight to the Allies who managed to glimpse it through the battle smoke. Walk this final chapter of Napoleonic history and begin to understand why the Garde might have split. By looking in the direction of the Lion Mound, the ground falls away naturally either side. Looking at Wellington’s line, the French must have known from earlier combat, that some 450 meters of the sunken road to the immediate west from Wellington’s centre would have been impassable, as it was now littered with battle casualties and debris from their own cavalry charges.

Stop in the valley some 300 yards short of Mercer’s Ridge (18). So confident were they, with their Parade Dress in their backpacks ready for the victory celebrations in Brussels that evening, the Imperial Chasseurs and Grenadiers now started deploying from column as they begin to climb the slope. It was here 3 hours previously that Ney’s cuirassiers had probably broken from trot into canter. After gaining the ridge (18a) you can imagine the actions of Colborne’s 52nd and how the two wings of this massive 1,034 strong unit had wheeled left in two ranks (some say four) under fire, taking 200 casualties, to decimate the left flank of the Chasseurs. Walk along to Mercer’s stone and view the position where his artillery pieces had been in front of the Brunswick squares at the time of the cavalry charges. Later, the Duke personally moved these young, inexperienced and frightened Germans to a more central position. Looking down into the valley bottom to the point of origin, again you cannot fail to see why Wellington had chosen this ground to defend. As the French cavalry, through the rye and mud for the first time, had endeavoured to breast the ridge at a full gallop from the valley bottom, there can be no doubt that finding the Allies infantry in squares behind cannon had surprised them. The reverse slope had again concealed the Allied defence.

Nosey, as the Duke was known, was a leader who was renowned for the morale of his troops. He was a commander who regarded those under him not only as a resource but as human beings as well. His duty of care is well documented and soundly reflects his discipline of, and love for, the army. He was a commander who was attentive to the requirements and provisioning of his troops, who paid his men daily to avoid drunkenness, who recompensed farmers and landowners well for billeting his units and who, in 1815, employed mixed formations to reduce desertions and boost confidence among the Allies. This track record surely demonstrates the importance Wellington placed upon morale. Indeed, it should come as no surprise to learn that of the ten doctrinal Principles of War that the British Military adhere to today, second to the most important principle, of Selection and Maintenance of the Aim, is the principle which Wellington’s legacy helped to create, Maintenance of Morale.

Wellington’s sense and duty of care was best demonstrated by his performance in battle. His practice of deploying his artillery in support of his Infantry and use of the reverse slope and dead ground for protection, are but two examples. By looking along Mercer’s Ridge (20) you can imagine both. From the same scene you can also imagine Wellington, as he did on the day, urging Copenhagen, his steed, northwards along the ridge, whilst giving orders on the move to those regiments to form line prior to the attack by the Imperial Guard.

When the situation was at its most fearful, Wellington kept his head and did not give way to the pressure of crisis. He had trusted himself, Blucher and his “finest instrument”… British Infantry. It had enabled him to hold the ground of vital importance against Napoleon’s artillery and all that came with it. The battle had been between the attacker and the defender. As the latter, Wellington had been patient, very aware and flexible throughout, using his tactical skill and experience to the full. These personal qualities formed the foundation stone of his leadership for this victory, as they had done at Salamanca, Vitoria, Talavera and all his conquests.

His bravery in exposing himself proved one admirable aspect of his leadership. Nevertheless, his greatest personal quality was surely that of courage. Had Kipling been beside Wellington at Waterloo during the crisis at 6pm, then one would have been certain from where his inspiration for his famous poem would have come:

If you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs and blaming it on you

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you but make allowance for their doubting too,

If you can wait and not be tired of waiting etc, …..

Finally walk the short route to Hougoumont Farm (19). On Napoleon’s ‘bad day at the office’, this is where mission creep went horribly wrong.

Instead of drawing the Allied reserve into combat, it achieved the opposite. The story here is most vivid. Unbelievably heroic and horrible scenes of battle with horses and soldiers burning to death, exhaustion of all involved beyond credible endurance, and with leadership, training and camaraderie stretched to the absolute limit … I have seen many a visitor here with tears in their eyes, not just because Chateau Hougoumont is the shrine to the British Guards but equally for the reason that the atmosphere is so heart-rending and unforgettable ………if Hougoumont fails to engage one’s imagination with history, nowhere else will. Today’s efforts by Project Hougoumont on behalf of Waterloo 200 are aimed at helping the Belgians renovate and restore the Farm to its original state including the Northern Gates on which Wellington attached so much importance.

Wander slowly back towards the Lion, pausing for the last time at the spot (20a) where, leading his brigade forward to protect Maitland’s left flank, (Colin) Halkett had been wounded. It was here that the Duke had inferred to Maitland that the time was right for British firepower from the Guards, and thereafter the 95th, the 52nd and the 71st. The resulting crescendo of volley subsequently decimated, first the front and then the eastern flank of the Imperial columns. The Garde had been stopped in its tracks. The world’s greatest fighting machine was to turn into a rabble inside 10 minutes. The campaign has cost 115,000 casualties after which Europe saw the rise of Germany, the thrust of Britain into greater empire, the demise of France and the downfall of the most written about soldier in history.

Whose Victory?

I have absolutely no doubt that, without the Prussians advancing to ‘the sound of the guns’ on that promise from Blucher, Wellington would never have decided to stand at Waterloo. During recent times the Anglo-German historian, Peter Hofschroer, has enlightened the public to the efforts of the Prussians. Certainly Wellington would have lost without their belated appearance. Nevertheless, without Wellington’s leadership and staying power, I fear there would have been no battle for the Prussians to save.

British Memorial

Culture Espace, a French Company, secured the contract to rebuild ‘Napoleonville’ and the tourist attractions that surround Mont St Jean, for the 200th Anniversary and to enhance the location for 300,000 visitors per year.

If we forget our history, we forget our standards, culture, and all that goes with our perception of remembering. Until the 200th anniversary of the battle, when walking Waterloo you will have noticed that something was absent when that concept is considered. There was no memorial to the British soldier. The Belgians, Dutch, Hanoverians, French and Prussians were all remembered with proud and prominent memorials on the battlefield.

In June 2015 this sense of duty to remember those Waterloo Men, many of whom paid the ultimate sacrifice, was realised with the unveiling a memorial to the British soldiers at Hougoumont Farm.

Editor’s footnote: If you are interested in the latest efforts at restoring elements of the battlefield then visit: http://www.projecthougoumont.com