In Literature and Song: The Legacy of the Napoleonic Wars

May 11, 2015 - Alwyn Collinson in News & Blog Posts, Guest Articles

This is a guest article by Emma Butcher and Anna Maria Barry.

The Napoleonic Wars had a profound effect on British culture of the early nineteenth century. Military memoirs carried vivid, personalised accounts of battle, while ballads, cartoons and dramas reflected patriotic fervour on street corners and stages throughout the country. Barely a single literary figure of this period was untouched by the events on the battlefield, with many of our most prolific writers being influenced significantly by the crusade against Napoleon. The stage during this period was also saturated with patriotism and hero-worship; musical tributes to heroes such as Lord Nelson achieved great popularity, and audiences flocked in their thousands to see ambitious re-creations of battles like Trafalgar and Waterloo. Napoleon’s defeat in 1815 did not signal the end of his influence; the events of the Napoleonic Wars continued to impact British culture for the duration of the century.

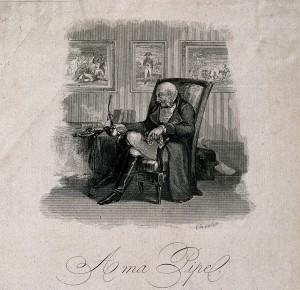

An old Napoleonic soldier sits dreaming in his armchair with pipe in hand, below a poem entitled “à ma pipe”. Engraving after N.T. Charlet. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

The influence of the world’s first total war is felt through the bountiful remnants of literature that survive from this period. We might talk of the glitz and glamour that the military brought to everyday society. Jane Austen’s writings, most notably Pride and Prejudice, identified the soldier as a fashionable, sexual being, who enlivened everyday society and enticed young girls into sin. From another angle, writers such as Sir Walter Scott were less concerned with social effects and more attracted to battlefields. Some of his most famous works indirectly addressed the contemporary conflict by focussing on Britain’s rebellious past, most notably through clan warfare. He introduced the reading public to first-hand combat; his protagonists were thrown into the midst of war and bloodshed, allowing the nation to envisage the chaos and terror of battle within their own homes.

The Romantic authors were deeply troubled by war’s devastating consequences. Poets such as William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey produced both anti and pro-war material that struggled to reconcile the destructive loss of life with conservative values of militarism and hero-worship. Although their initial anti-war poetry branded the Romantics as fully radicalised and anti-government, by the turn of century, each poet had completed their transformation into patriots, producing stirring, warmongering verse that united militarism and the arts.

Unlike his contemporaries, Lord Byron spoke openly about his hatred of war and support for Napoleon. A majority of the Romantics were obsessed with Napoleon, producing multiple representations of this powerful, menacing figure. Many even attempted to understand and negotiate their own selfhood through adopting Napoleon as a literary muse: in Don Juan, Byron calls himself ‘the grand Napoleon of the realms of rhyme’. After Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, Byron remained loyal to his hero, branding the battle as merely a ‘king-making Victory’.

Waterloo remained an iconic moment in the late-Georgian literary imagination, the site a place of pilgrimage that provoked sentimental outbursts of lyrical creativity. Notable poets like Byron, Scott and Southey all lamented the large-scale loss of life, their emotional responses capturing the mournful echoes of a grieving nation. Byron directed his anger through Cantos III of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage:

Let their bleached bones, and blood’s unbleaching stain,

Long mark the battle-field with hideous awe:

Thus only may our sons conceive the scenes we saw

Byron never made peace with Waterloo. In his later mock epic, Don Juan, he directly attacks England’s vanquisher, the Duke of Wellington, asking:

And I would be delighted to learn who,

Save you and yours, have gained by Waterloo?

In the years of peace that followed Wellington and Napoleon’s climatic confrontation, the subject of war continued to resonate in popular culture. Many thought that the post-war period was a dull, lifeless time; Benjamin Disraeli remarked in Vivian Grey: ‘we really must have a war for variety’s sake. Peace gets quite a bore’. The public, however, were still able to relive the conflict of recent years through first-hand accounts, either individually published or included in periodicals such as Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine.

The rise of the military memoir contributed to the public consciousness of war. Whereas, in previous battles, armies had generally been viewed en-masse with no attention given to individual men, this outpouring of military autobiography contributed to the treatment of soldiers as individuals. Britain began to take an interest in individual soldierly experience, caring about ‘the man behind the uniform’.

Over 200 military memoirs were published in the years following the Battle of Waterloo. These were written in a number of styles, ranging from romantic stories to picturesque travel narratives. However, most importantly they supplied the everyday person with a direct vision of combat. One of the first and most popular memoirs, Journal of a Soldier of the Seventy-First, written in 1819, is an epitomising example of a memoir that gives a vivid, sentimental account of battle. In this particular section, the narrator reflects upon the battle of Waterloo:

Many an action had I been in, wherein the individual exertions of our regiment had been much greater, and our fighting more severe; but never had I been where the firing was so dreadful, and the noise so great. When I looked over the field of battle, it was covered and heaped in many places; figures moving up and down upon it. The wounded crawling along the rows of dead, was a horrible spectacle

Many post-Waterloo memoirs contain similarly emotive responses to battle, allowing a post-war generation to understand and process battlefield experience. If we dig a little deeper, these memoirs also uncover some of the more traumatic imprints of war. In another popular memoir, Thomas Gleig’s The Subaltern, a petrified watchman informs Gleig that he saw a group of devils dancing by a lake. A white figure then came groaning towards him before he saw a dead soldier sit up and stare him in the face. In another untitled memoir, published in the New British Novelist, a soldier describes a distressing experience in Paris’s catacombs whilst touring the capital briefly after the battle of Waterloo:

A thousand hideous forms of darkness seemed to flit past me, – the skulls with their eyeless sockets, seemed to scowl upon me, – my head became dizzy, – the vaults, with their skeleton pillars spun me in the dance of death, – my brain reeled, and I fell against a crashing pile of mortality, where I swooned away.

In a period where trauma was absent from medical terminology and categorised under titles such as ‘cannonball wind’, these intimate accounts of men who survived yet are haunted by death encouraged a revisionist, negative response to war, such as Byron was channelling.

The prevailing response to militarism was, however, patriotic. Nowhere was wartime patriotism more vividly reflected than on the stage. At half past eleven on the evening of Wednesday 21st June 1815 Wellington’s victorious dispatches were announced to crowds at Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens. As The Morning Chronicle later reported, ‘the Bands were instantly directed to perform the National Airs of See the Conquering Hero Comes, and God Save the King, in which the whole company participated with the most enthusiastic joy.’ Entertainment venues such as Vauxhall offered the public a place in which they could to come to celebrate victories, mourn heroes and express their nationalism through patriotic music and dramas.

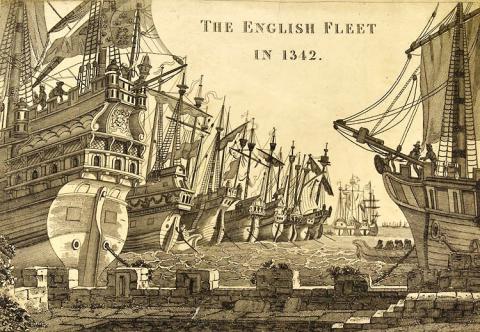

On the stage, popular dramas often reflected British naval pride and an antipathy towards the French. One such example was The English Fleet in 1342, a comic opera that was performed at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden in 1803. The plot of this opera, depicting a historic English naval victory over the French, was a thinly veiled attempt to appeal to the nationalistic feelings of an audience that lived in fear of attack from Napoleon’s forces. A reviewer writing in The Times noted the resonance of the theme, remarking that ‘Many of the situations are applicable to the present state of this country; and the sentiment, without any great straining, may not be deemed inappropriate to the ardent zeal and enthusiastic patriotism by which all ranks of people are animated in defence of their dearest rights.’

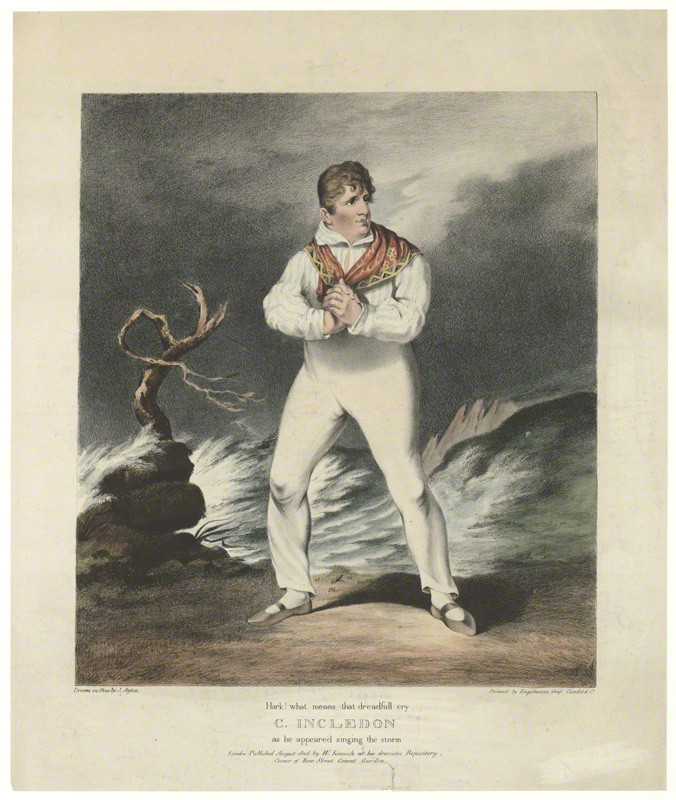

The English Fleet also starred two British singers who achieved great popularity during the Napoleonic Wars; Charles Incledon and John Braham. Incledon had served in the Navy before he took to the stage, gaining a reputation as a singing sailor. His songs celebrated the heroism of the Navy and were always performed in a sailor’s costume. One such example, ‘May the King Live For Ever!’ featured the lines:

May the KING live for ever!

The glory, the pride of our isle.

How needless to talk of our prowess in war,

Or proclaim what the universe knows;

Let the Tyrant of France, and his allies declare

What it is to have Britons for foes.

Print of Charles Incledon performing ‘The Storm’ in costume as a sailor. The National Portrait Gallery, London.

During the Napoleonic Wars Incledon also served in the Duke of Cumberland’s Sharpshooters, a sort of ‘Dad’s Army’ that was established to defend Britain in the event of a French attack. This unit, consisting largely of ageing and unfit theatrical personalities, was unlikely to have offered much defence had Napoleon invaded. The over-weight Incledon’s inability to keep up with the unit’s drill exercises on Hampstead Heath was lampooned by contemporaries.

Braham was arguably the most famous British opera singer of the nineteenth century, and his own reputation as a national hero was cemented during the Napoleonic wars. This was due to his popular performances of patriotic anthems, most notably his own renowned composition ‘The Death of Nelson’. Braham had been friends with Lord Nelson, with whom he had often dined with, and had been in the unusual position of teaching music to both Frances Nelson and Emma Hamilton. Braham’s musical tribute to his fallen friend achieved extraordinary success and was still being printed and performed in the latter years of the nineteenth century. The rousing anthem opened with the lines,

‘Twas in Trafalgar’s bay

We saw the Frenchman lay,

Each heart was bounding then.

We scorned the foreign yoke,

For our Ships were British Oak,

And hearts of oak our men!

Emma Hamilton herself was particularly fond of this song, and was known for becoming hysterical at Braham’s public performances of it.

It was not just Napoleonic heroes that were depicted on stage; entire battles were re-created for audiences at great expense. Sadler’s Wells, managed by the patriotic composer Charles Dibdin, was home to elaborate aqua-dramas. Its stage was flooded with water for performances such as The Siege of Gibraltar, which was performed in 1804. This production featured over 100 replica ships, built and rigged by workers at the Woolwich Docks. Children were employed to depict drowning Spanish sailors and the performance featured gunfire and explosions. Although this performance depicted a British victory of the American War of Independence, its staging of a famous defeat over the French was unsurprisingly popular at a time when Britain found itself once more at war with France.

The Battle of Waterloo was also recreated for audiences. Wellington himself enjoyed one particular re-enactment of the battle so much that he attended twice. In his military memoir the British officer Henry Austin stated, ‘I shall not be far wrong in asserting that there exists not in the United Kingdom, man, woman, or child, who has not either seen pictures or panoramas of Waterloo, heard songs on Waterloo, read books on Waterloo, talked for weeks about Waterloo’. The popularity of Waterloo persisted; Astley’s Amphitheatre was still staging dramatic representations of the Battle as late as 1853, almost 40 years later. Only a few years previously, Thackeray’s Vanity Fair had taken the country by storm, another testament to the excitement of past Napoleonic campaigns. In his novel, we get a true image of the lasting impact of Waterloo:

The tale is in every Englishman’s mouth; and you and I, who were children when the great battle was won and lost, are never tired of hearing and recounting the history of that famous action. Its remembrance rankles still in the bosoms of millions of the countrymen of those brave men who lost the day.

Large-scale battles and military figureheads gave rise to a century that celebrated and memorialised heroism and conflict. In the early nineteenth century Britain, the word on everybody’s lips was war, and through literature and song, the Napoleonic conflicts endured.

Emma Butcher and Anna Maria Barry are PhD students who specialise in the popular culture of the Napoleonic period. Emma works on the representation of the Napoleonic Wars in the juvenilia of the Brontë siblings. She has co-curated an exhibition called ‘The Brontës, War and Waterloo’ at the Brontë Parsonage Museum. Anna’s research concerns the representation of Napoleonic Wars on the British stage. She is especially interested in the relationship between British opera singers and the navy and is curating an exhibition on opera singer Charles Santley at Liverpool Central Library. Together, Emma and Anna have organised a major international conference to mark the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo. This will be held at the University of Hull in May and is endorsed by Waterloo 200. Further details can be found on the conference website: http://militarymasculinities.wordpress.com/.