Captain Edward Kelly’s Letter from Waterloo

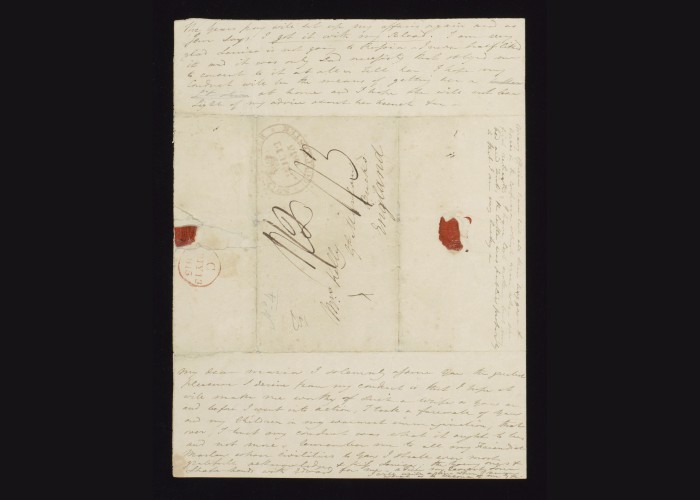

This is a letter from Captain Edward Kelly to his wife, describing the Battle of Waterloo. Kelly served at Waterloo with the 1st Life Guards cavalry regiment. During the battle Kelly distinguished himself by fighting and killing the Colonel of a French Cuirassier (cavalry) regiment, but was later seriously wounded in the fighting.

Kelly wrote this letter of 6th July 1815 to his wife, from his sick bed, reassuring her that while his wounds were serious, they were not life threatening and that he was healing well, if slowly. He describes it: “My wound though not at all dangerous is, I am sorry to say, likely to prove tedious and painful.”

He provided an account of his combat with a senior French officer, Colonel Habert of the 4th Cuirassier regiment, in which Habert died. Kelly stopped to cut off the Colonel’s epaulettes as a keepsake, and also briefly took his horse but later lost this to another French attack. Later in the battle, Kelly was seriously wounded and was unable to continue fighting.

Kelly mentions that his gallant actions had been mentioned to the Duke of Wellington and that he hoped the Prince Regent and the Duke of York (head of the Army) might hear of it too. His letter reveals his hopes for promotion to Lieutenant Colonel as a result of his valour (Kelly’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Ferrier was killed in the battle), but also that he does not expect to get it. Kelly expresses negative views of some of his fellow officers, who feigned injury or made excuses to avoid fighting, but later sought to advance their careers. This provides an interesting view of the rivalries and jealousies that existed between officers, even during such a major battle.

Kelly did receive rewards for his actions, receiving the Order of St Anne from the Tsar of Russia; Kelly later gained his promotion to Lieutenant Colonel and went to command the 23rd Light Dragoons in India, where he died and was buried in 1828, aged 54.

Read a transcript of Kelly’s letter below.

My dearest love, I have at length had two letters from you after almost having gien up the idea…. if I had not something to remind me that I am not immortal, your praise and the manner in which you are pleased to overrate my little services would almost turn my brain.

My wound though not at all dangerous is, I am sorry to say, likely to prove tedious and painful, and the chief medical officer here has been to inspect the wounded officers to have those sent to England whose cure is likely to be protracted and I am sorry to say my name is among the number. The small bone of my leg is fractured and before the wound, which is very large, can heal exfoliation of the bone must take place. However I bear mu suffering better than my confinement, and now that I am out of bed, that also become less irksome.

The wounded officers are almost all doing well and nothing can equal the kindness of the inhabitants of this town to us all. The Gallant Marquis of Anglesea sent me word that he had already mentioned my name to the Duke of Welington and that he would also mention me to the Prince [Regent] and the Duke of York, so that I think there will be a race between me and [Captain John] Whale for the Lt. Colonelcy, and God knows I won it fairly in the Field, but I think there is no chance of my getting it.

The men and officers who fought with me in the Field are enthusiastic in my favour, but there are some officers, who were absent from some idle excuse or other, who are envious of my praises. One you mentioned in your last letter might have been killed in the Field on Sunday but he reported himself wounded from a scratch and when he found [Lt. Col] Ferrier was killed, he posted off to take command of the Regiment. This must be kept to yourself.

I offered the French Colonel’s epaulettes to Lord Uxbridge, but he said he could not think of depriving my family of them. I got his horse also – a most noble one – but being attacked by a number of French at the same time, I was obliged to let him go and should have been killed but for our Corporal Major who fought bravely by my side till we laid them down never to rise again. I have mentioned him to Lord Harrington.

In about another week I shall be able to give you a more exact account of myself. I shall avoid going home if I can, but if I am to be six weeks or two months laid up, I had better be in England than here as all the wounded are going who have not a prospect of joining the army soon.

Lord Combermere will put me on the Staff here when I am able to do duty, at least he promised he would before I cam out. How lucky I was not on the Staff before, or I should have lost this glorious opportunity [by] which I sought to distinguish myself. When I go to England, I shall write for you to meet me. Before I went into action, I took a farewell of you and my children in my warmest imagination.

G. K.

[PS} Many officers have lost all their baggage and horses in the confusion which arose when we first retreated. I have lost nothing but my bed and tent; the latter was public property so that I am very lucky. Remember me to Daisy; tell her Donnybrooke Fair was nothing to the fight we had there and that here was a great number of spare wigs on the green. When you see Henry, tell him to sport 1s 4d [postage] on a letter to me.

Billing has just gone to order a pair of crutches for me and in a day or so I hope to be able to hop out a little. The great discharge from my wound keeps me very low so that they allow 3 glass of wine per day. Adieu, ever yours, G.K.

-

Curatorial info

- Originating Museum: National Army Museum

- Accession Number: NAM. 2002-01-254

- Production Date: 1815

- Creator: Captain Edward Kelly

- Material: Paper, ink

- Creation Place: Brussels

-

Use this image

You can download and use the high resolution image for use in a non-profit environment such as a school or college, but please take note of the license type and rights holder information below

- Rights Holder: Copyright National Army Museum.

- License Type: Creative Commons

Find it here

This object is in the collection of National Army Museum