Wellington’s Places: Stratfield Saye

March 19, 2015 - Alwyn Collinson in News & Blog Posts, Guest Articles

This is a guest article written by his Grace the Duke of Wellington.

Stratfield Saye was the seat of the first Duke of Wellington, given to him by a grateful nation in the aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo.

Stratfield Saye. Copyright Stratfield Saye Preservation Trust.

At the time of the Battle of Waterloo, a beautiful stately home already existed at Stratfield Saye. The original red-bricked, gabled Carolean house was bought by Sir William Pitt, comptroller of the household of King James 1, from the Dabridgecourt family.

His great-great- grandson George, was made Lord Rivers in 1776. Rivers had served as British Ambassador in Turin and Madrid, and on his retirement he set about improving the house and re-landscaping the grounds. He built a church in the park, stuccoed the house, created the walled gardens, felled the formal avenues and, in the fashion set by Repton, opened up the surroundings. He sashed the windows, slated the roofs, created the gallery that runs along the south side of the house and decorated it with prints. He added the dining room with its bay windows and built a range of kitchen buildings to the north. And it was he who decorated the ceilings of three of the rooms on the river side with papier mâché rocaille giving the house an unusual delicacy and European feeling, presumably as a result of his experiences abroad.

Wyatt’s design for a Waterloo Palace. Copyright Stratfield Saye Preservation Trust.

By 1817 the 2nd Lord Rivers was looking to sell the house and offered it to Wellington who had employed Benjamin Dean Wyatt, the architect, to look for a suitable estate for his now famous family. The new Duke bought it with the monies voted him by the government of the day, in gratitude and recognition of his outstanding service in the wars against Napoleon, culminating in the victory at Waterloo.

The plan was to pull the house down and build a palace on another site in the park. Drawings were submitted by C.R. Cockerell, C.Tatham and B.D. Wyatt for a building to rival Blenheim. Wyatt’s project, estimated to cost £216,850 15s 3d, included a dome copied from the parthenon, a circular colonnade, state rooms and £4,000 worth of gilding.

Wellington, however, chose not to build and settled for the old house. He preferred comfort over grandeur and set about achieving the former. He installed central heating and some double glazing, boasting to Princess Lieven, his friend,

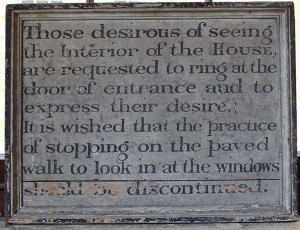

‘there is not a passage or staircase at Stratfield Saye which is less than 64 degrees’. Beautifully veneered water closets were installed in cupboards in the bedrooms with every consideration given to light, ventilation and sound-proofing. Inspired by the 18th century decoration of the gallery he supervised the installation of 8 print rooms, added a conservatory and built onto the wings. The 1st Duchess slept on the first floor in the east corner of the house and the Duke on the ground floor in the west. However privacy was less easily achieved and the Duke was sadly plagued by admirers and the inquisitive.

Lord Douro, Lord Charles Wellesley and Gerald Wellesley, their cousin, in Eton dress in the park at Stratfield Saye, in c.1820. They are in mourning for King George III.

When Wellington decided against the new ‘palace’ in the park, he was in great part influenced by his wife and sons, who were 10 & 8 years old when they came to live at Stratfield Saye. Like him their taste was not for grandeur, like him they enjoyed the privacy of country pursuits: riding, shooting, hunting and fishing.

Kitty, the 1st Duchess, had been brought up in Ireland, the daughter of Lord Longford. She was 34 when she married the Duke and 44 when she came to Stratfield Saye. Here she read a great deal and corresponded with her friends about her reading. She enjoyed needlework, the piano and walking in the grounds. She was an accomplished draftswoman, but possibly her greatest gift was her ease with and affection for all the children of the house.

Kitty’s Sketch

God children, nieces, nephews and great nieces and nephews made up an extended family whose care Kitty took to heart. Arthur Freese, a godson, came to live with them when he was sent home from India to live with an aunt who died. Wellington (then Wesley) had been a great friend of his mother. Her portrait hung in the house. Gerald Wellesley, a nephew, the son of Lord Cowley; Kitty’s niece, Kate Hamilton; Lord Arthur Lennox, another godson; and 3 Long-Wellesley children (2 great nephews and a great niece) all lived on and off as part of the family. Kitty entered into their confidences and was adored in return.

There is a vivid correspondence between Kitty and all the boys when they were sent away to school in which more often than not the adolescents condescend to her as a much-loved creature needing their protection rather than the other way round. The Long-Wellesley children tragically became wards of the Wellingtons after the death of their mother. Neglected by their father they arrived wayward and ill-educated only to be brought round by Kitty’s affection and to care for her in their turn. There were animals, a collection of birds and make-believe which amused them all. However her informal charm, whimsical sense of humour and childish enthusiasms were more difficult to fit into her husband’s sophisticated circle of friends and acquaintances. On one occasion Wellington complained to Mrs Arbuthnot, one of his many female correspondents, ‘that her [Kitty’s] mind was trivial and contracted’.

Kitty was shy, short-sighted and had no interest, unlike Mrs Arbuthnot, in politics. She was lovingly attentive if undisciplined and a little vague with her charges. (Her elder son wrote home to complain of the ‘great deficiency’ of pocket handkerchiefs she had sent the boys to Eton with, – sixteen missing between him, his brother Charles and Cousin Gerald.) But despite all the children she was often alone in the house and a tragic prey to depression. Her marriage was often a lonely one but it was reconciled and settled into great affection before her death in 1831.

Queen Victoria’s Visit

In 1845, when Wellington was 75 years old, Queen Victoria came to visit. He had tried to put her off:

‘Alas it is but true’ he complained to a friend, ‘the Queen is coming to pay me a visit at Stratfield Saye. I did everything I could to avoid the subject – never mentioned the word and kept out of her way’ and when she insisted, he said, she would: ‘find my House, however comfortable as a Gentleman’s residence but small and inconvenient as the Residence of Her Majesty’s Court. She smiled and continued to be very gracious but did not give a hint of postponing the visit’.

He continues:

‘The difficulty under which I am about, besides the numbers to be received in comparatively a small house, consists in having no State Apartment: Her Majesty’s Court requiring a sitting room as well as the usual lodging room and best rooms for their attendants, not few in number. Bells must be hung from Her Majesty’s Apartments into those for her attendants. Walls must be broken through’.

Mrs Apostles, his housekeeper, near to tears, objected: ‘My Lord, your house is a very comfortable residence for yourself, your family and your friends. But it is not fit for the reception of the Sovereign and her Court’.

‘What cannot be prevented must be borne’, the Duke replied.

The Queen wrote in her diary,

‘Stratfield Saye is a low and not very large house but warm and comfortable with a good deal of room in it’.

Her bedroom she described as ‘snug’ to which the Duke himself lit her to bed each night.

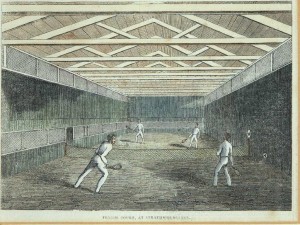

‘He was very attentive’ she continues in her diary, ‘For luncheon we sat a small table, the others being at another one. The Duke helped us himself –rather funnily, giving such large portions and mixing up tarts and puddings together’. However the visit was deemed a huge success and Prince Albert learned to play real tennis.

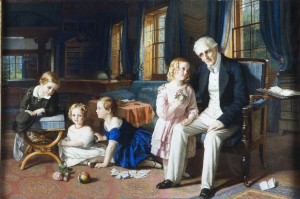

The Thorburn painting of The Duke surrounded by his grand-children in the library at Stratfield Saye. The boy in blue became the 4th Duke.

The Duke lived on at Stratfield Saye for a further 21 years and this time the rooms rang to the sounds of the Duke’s grandchildren, who he regularly had to stay, often without their parents. On these occasions he would write to his daughter-in-law, Lady Charles Wellesley, every day. The letters reveal him as a concerned and interested grandfather- in 1850 he wrote,

“your children have caught colds, even the baby. But I have just now been up to see them… I could not bear that they were unwell without seeing them and without letting you know how they were”. The grandchildren used to sit with their grandfather in the library, while he opened the daily post, and they would collect the envelopes and stamps and they were painted at this occupation by Robert Thorburn in 1852.

The Duke of Wellington

The 1st Duke of Wellington wearing field marshal’s uniform with Order of the Golden Fleece, star of the Order of the Garter and other decorations, by Thomas Phillips

Arthur Wellesley was born in Dublin on 1st May 1769, the 3rd son of the 1st Earl of Mornington. He was educated at Eton and a French military riding establishment in Angers.

In 1787 he entered the army as an ensign in the 73rd Highland Regiment.

By 1796 he was a Colonel of the 33rd regiment of Foot and spent the next 9 years in India campaigning against a coalition of Princes who were friendly to the French. In 1803 he was a Major-General and won a significant victory at Assaye, for which he was knighted. In 1806 he married Catherine Packenham, daughter of Lord Longford. While still serving as a soldier he was appointed Chief Secretary of Ireland.

He went on an expedition to Copenhagen and in 1808 was promoted Lieutenant-General and left to command 14,000 men in the Peninsular. In 1808 he fought the battle of Vimeiro which victory led to an armistice in Portugal and the withdrawal of the French troops. Wellington went back to Ireland but returned to Portugal in 1809, resigning his position as Chief Secretary for Ireland.

He cleared Portugal of the French and moved into Spain and won the victory of Talavera in June that year. For this he was given a peerage, Viscount Wellington. However he then had to retreat in the face of overwhelming odds to Portugal where he defended his position with the ‘lines of Torres Vedras’ By March 1811 the French went back to Spain.

In early 1812 Wellington captured Ciudad Rodrigo after a relatively short siege, for which he was made a grandee of Spain and given the title of Duke of Ciudad Rodrigo, and in Britain, Earl of Wellington. Two months later he took Badajoz, which had been besieged twice before. The final capture was bloody and long drawn out. In July 1812 he gained another victory at the Battle of Salamanca, which opened the road to Madrid.

Wellington was welcomed in Madrid by the populace and painted by Goya.

In June 1813 he defeated the French, under Joseph Bonaparte, at Vitoria. For this the British promoted him to Field Marshal and the Spanish Cortes gave him a property in the province of Granada (which is still owned by the family). Wellington crossed into France in October 1813 and by April 1814 Napoleon had abdicated. Wellington was made a Duke.

In July 1814 Wellington was appointed Ambassador to the French court. He remained in Paris until January 1815, when he joined the Congress of Vienna as the British representative. In March, Napoleon escaped from Elba and landed in France. Wellington travelled to Brussels to assemble an army. In June he defeated Napoleon at Waterloo. The Duke remained in France as Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Army of Occupation.

Parliament voted him a considerable sum of money to buy, ‘a lasting memorial to show gratitude and munificence’. Wellington chose the estate of Stratfield Saye.

In 1818 he entered serious politics and was appointed Master-General of the Ordnance in Lord Liverpool’s Cabinet. In 1828 he became Prime Minister. He passed the Catholic Emancipation Act and fought a duel with Lord Winchilsea over the founding of King’s College London. He resigned at the end of 1830.

In 1831 the Duchess died in London during the rioting over the Reform Bill.

In 1834 he was made Chancellor of Oxford and Prime Minister for 6 weeks, waiting for Peel’s return.

In 1842 he resumed command of the army until his death in 1852, aged 83, at Walmer, the residence of the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. He was buried after a state funeral at St Paul’s Cathedral.

This is the third in a series on “Wellington’s Places”. Read about Apsley House, Wellington’s London home, or Brynkinalt Hall, one of his childhood residences. Read about the Duke of Wellington’s curious rent of one silk flag given to the monarch every year in payment for Stratfield Saye.