The Surgeon’s Blade: Battlefield head wounds and trepanning

March 29, 2018 - Mick Crumplin in The Surgeon's Blade, News & Blog Posts

For his latest medical blog Mick Crumplin discusses head wounds on the battlefield and the ancient medical practice of trepanning

Of all wounds inflicted in warfare, roughly 20-25% of them are head injuries. With modern day treatment, about 80% or more patients will survive to serve a ‘useful’ life. The bony skull or cranium protects the cerebral matter (the brain), which has the consistency, in life, of firm jelly.

Apart from decapitation and very severe crushing or penetrating injuries, there are a number of survivable head wounds. Concussion occurs when there is a temporary loss of consciousness and there is only microscopic damage to the delicate brain tissue. When consciousness is regained, there may not be much in the way of lasting damage.

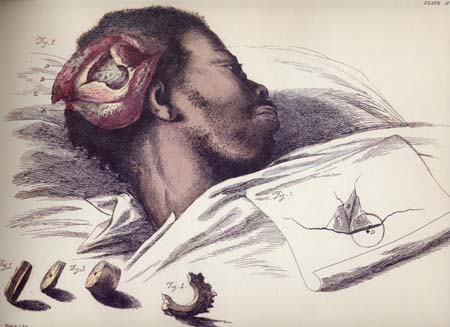

The skull can be fractured with or without underlying brain injury. The risks with a skull fracture to the brain are several. If sharp fragments of bone are depressed into the brain, irritability, epilepsy, bleeding and infection may occur. Infection is a big threat if the protective covering of the brain – the dura mater – is torn.

“To reduce the rise of pressure from bleeding, to lift in-driven bone shards, to remove missiles and check the integrity of the dura mater, trepanning was employed”

The other problem is when blood collects inside the skull and cannot escape. This haematoma (a collection of blood) expands, compresses the brain, raising intracranial pressure and pushes the brain down into the base of the skull, with fatal consequences.

To reduce the rise of pressure from bleeding inside the skull, to lift those in-driven bone shards, to remove missiles and check the integrity of the dura mater, trepanning was employed. This meant incising (cutting) the scalp, which bleeds a good deal, then by turning a small circular saw on the skull surface, one or more small discs of bone would be removed. These defects just gave the surgeon enough space to control haemorrhage, remove debris or lift depressed bone pieces. The hole (or holes, since the surgeon could make several if more space was required) made in the bone never healed under the healed skin and sometimes a protective cover was supplied.

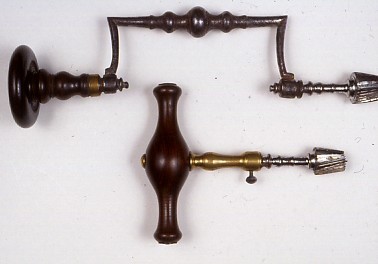

In former years (in the 17th and early 18th century), particularly on the continent, a brace-and-bit type of circular saw (top image below) was used, but In 1639, a naval surgeon, John Woodall, popularised an older but more efficient instrument, the simpler trephine (bottom image, below).

This shorter instrument allowed the operator more accurate control of his actions, which were made closer to the bone surface. Gentle twisting through the two thin layers of skull bone, just clear of the fracture site, created the round defect. The little saw, whose circular blades came in various diameters, had a retractable central spike, to prevent the saw ‘skiting’ across the bone surface. After the defect was made by the surgeon, other instruments would be used to carry out the procedures mentioned above.