The Surgeon’s Blade: How Nelson lost his arm

September 5, 2017 - Mick Crumplin in News & Blog Posts, The Surgeon's Blade

Mick Crumplin continues his Napoleonic era medical blog by looking at Nelson’s trauma at Tenerife

Richard Westall, Nelson wounded at Tenerife © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Greenwich Hospital Collection

Lord Nelson was a leader both inspirational and impetuous in style. He would often pay a price for these traits.

In the early years of the Napoleonic war, the Royal Navy was having considerably more success than the nation’s land forces, but after the success off Cape St Vincent in February 1797, the British fleet in the Mediterranean was struggling against the Spanish Navy at Cadiz. To try and better the fleet’s performance and possibly gain a Spanish prize ship at Tenerife, Rear-Admiral Horatio Nelson was detached with a Squadron to assault the Spanish island, at the port of Santa Cruz in July 1797.

His squadron consisted of HMS Theseus, Culloden and Zealous (all ‘74s), Leander (50), three frigates and some smaller vessels – in all 400 guns and 4,000 sailors and marines. Arriving on 17 July, the Spanish were forewarned of the attack and the combined operation on 22 July was a failure.

“Refusing assistance, with his three limbs, he clambered up the tumblehome.”

Nelson, leading from the front, clambered on to the mole jutting out from the port. As soon as he was struggling onto the jetty, he was hit, probably by a lead musket ball, in the right arm – above the elbow. The humerus (arm bone) was shattered and the brachial artery was bleeding profusely. Nelson’s accompanying stepson, Josiah Nisbet, stripped off his silk stock and, after tying it and a second one, tightly around the arm, above the wound, took Nelson’s bicorne hat and covered the injured part, to hide the blood loss from the wounded admiral.

Nelson refused his cutter to be rowed to the nearest ship the frigate Seahorse, where the wife of Captain Freemantle (who had also been wounded in the landing) was on board and being perhaps less happy with the ship’s surgeon, he moved onto the Theseus.

Refusing assistance, with his three limbs, he clambered up the tumblehome and straightway ordered the sip’s surgeons (Messrs Eshelby and Remonier) to prepare for his surgery. He bore the 15-minute high above-elbow amputation calmly. His only complaint was that the instruments were cold. He disliked the sensation and ordered all squadron surgeons to warm their instrument before using them!

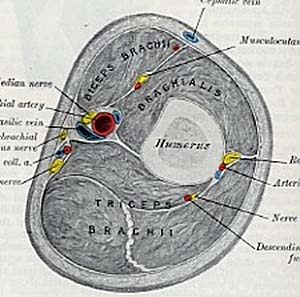

Cross section of the arm approximately at the level of nelson’s amputation. The proximity of the median nerve (yellow) and the brachial artery is close (Authors’ collection)

When asked what was to be done with the severed arm he told the surgeons to throw it into the weighted hammock alongside the corpse of a dead sailor, who had bravely died of wounds after the assault on the mole. Receiving only three doses of laudanum after the surgery, he became understandably gloomy. He also became constipated after the analgesics.

The surgery was for several months complicated by considerable stump pain. A branch of the median nerve had almost certainly been included in the arterial ligature. Repeated expenditure and medical consultations failed to alleviate the pains. Suddenly on 4 December 1797, the ligature after remaining stubbornly protruding from the wound came away and Nelson was mercifully free of his torment.

The following year, on August 1 1798, he would gain a brilliant victory in Aboukir Bay – the Battle of the Nile. He was once again wounded in this action.