The Surgeon’s Blade: Lieutenant George Simmons ‘Most Dangerous Wound’

November 2, 2017 - Mick Crumplin in The Surgeon's Blade

Mick Crumplin continues his medical blog with the story of the terrible suffering and survival of a young officer in the Peninsular Wars and at Waterloo

It is nigh impossible to imagine how much this young officer suffered after being desperately wounded at the Battle of Waterloo. He was incredibly fortunate to have survived.

George Simmons of the 1st Battalion 95th Rifles, was wounded in the thigh at Almeida (1810), also then suffering a ‘spent’ ball wound in the leg. In 1814, near the end of the Peninsular War, he received a severe wound of the knee at Tarbes in the Pyrenees.

The 95th Regt. (Rifles), near the sandpit, c. 1345hrs. 18 June 1815 (With permission and copyright of Steve Stanton)

Following the Battle of Waterloo, on the 1 July 1815, George wrote to his parents, telling them that after four hours of combat, probably in the region of La Haye Sainte Farm, he was dangerously wounded by a musket ball, which had entered his right side and passed though the chest wall, breaking two ribs.

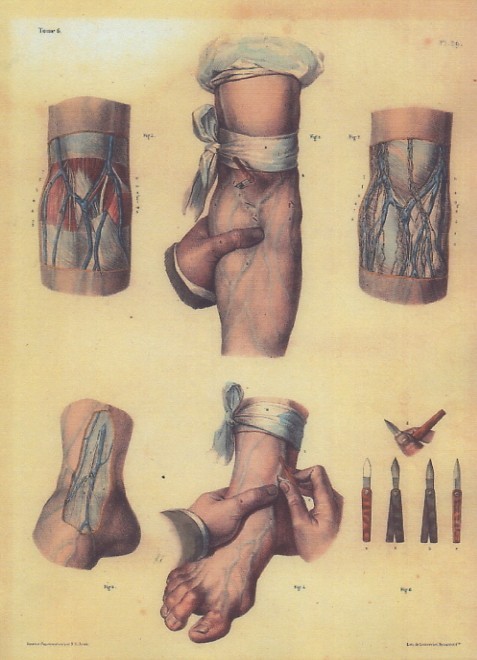

Tracking on through the right lobe of the liver, the missile exited the chest and lay under the skin, near Simmons’s right nipple. After being trampled on several times, he was dragged to a building, possibly Mont St Jean Farm, where a surgeon cut into the skin, fat and muscle and extracted the ball (later given to a relative of Simmons).

Suffocating with the blood and air in his chest, a surgeon bled George of two pints of blood. A horse was obtained and he was helped onto the beast by a life guardsman. Arriving at about 10pm, at his Brussel’s billet, he was tenderly cared for by the protestant Mr Overman and his family and a further quart of blood was removed from an arm vein. Despite this awful wound, George remained worried about money matters. On the 3 July, he suffered, fever, convulsions and vomiting.

He was bled 2 or 3 times each day for a week (to reduce inflammation). This infers the removal of 4 to 5 litres of blood over 8 days!! He believed, commensurate with traditional medical thinking, that, ‘The lancet was the only thing to save me.’ As another week wore on, Simmons was now desperately weakened, faint and he felt a fullness, pain and swelling in his upper abdomen.

After one venesection had caused a prolonged fainting episode, a worried companion brought a physician to see George. Thirty leeches were applied to his flank and twenty five more the next day. These caused him agonising pain, so he ordered the 80-odd leeches in his billet to be destroyed! After this Simmons consoled his friend, the regimental assistant surgeon and his nurse that he was resolved to die, and that, ‘Death has no pangs for me.’

Comatose for three days and near to death, George woke, one morning to find his bed soaking wet. An abscess had formed above the liver and found a way out through the entry wound. Purulent material gushed out and the patient was to survive with a prolonged road to recovery. His profound sepsis and the massive amount of blood removed had left him grossly anaemic and in mild cardiac failure with swollen legs.

Some weeks later, he was observed out walking with two young women supporting him. These incredible sufferings were to be the legacy for so many young men who had survived these two long wars.