Wellington’s Funeral Carriage

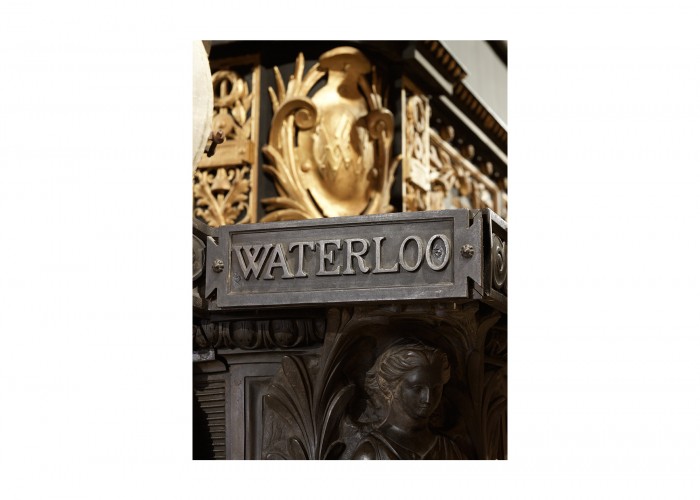

The Duke of Wellington is one of only a handful of non-royals to have been accorded a state funeral. This carriage or ‘car’ was made for the occasion. It was cast from over 10 tons of bronze cannon captured at Waterloo. Six foundries employed over 100 men for 18 days to make it.

The resulting creation measured 27ft (8m) in length, 10ft (3m) wide and 17ft (5m) high. A canopy of silk and silver hung from four halberds above the main structure. It required 12 horses to pull it.

The car proved to be the most controversial feature of Wellington’s funeral on 18 November 1852. Prince Albert, who oversaw the project, decreed that it should be ‘a symbol of English military strength and statesmanship.’ His wife, Queen Victoria, loved it. Lord Hardinge, the Duke’s successor as commander-in-chief, reckoned it ‘a beautiful specimen of art’.

Philosopher Thomas Carlyle, however, dismissed it as ‘an incoherent huddle of expensive palls, flags, sheets and gilt emblems and cross poles’. Writer Charles Dickens was even more critical. He judged that ‘for forms of ugliness, horrible combinations of colour, hideous motion and general failure, there never was such a look achieved as the car’.

It did not help that one of the carriage’s six wheels got stuck in The Mall during the elaborate funeral procession. About 60 policemen were needed to free it. Worse, when it reached St Paul’s Cathedral, its mechanism failed. It took over an hour for the Duke’s coffin to be conveyed inside. The car then found a home in the crypt of St Paul’s until it was transferred to the Wellington family estate at Stratfield Saye, Hampshire, in 1981.

Despite such shortcomings, Wellington’s funeral was one of the great British state occasions of the 19th century. An estimated 1.5m people converged on the procession route. The general feeling was that the passing of the hero of Waterloo marked the close of an era. The poet Alfred Lord Tennyson went even further, declaring that ‘the last great Englishman is low’. Certainly there was nothing to compare to it until Sir Winston Churchill’s funeral in 1965.

-

Education overview

Further reading. R. E. Foster, ‘Burying the Great Duke. Thoughts on Wellington’s Passing’ in C. M. Woolgar (ed.), Wellington Studies, V, Southampton, 2013, pp. 299-328.

-

Curatorial info

- Originating Museum: Stratfield Saye

- Production Date: 1852

- Material: Bronze, black velvet, silver thread, wood

- Size: Length 21 feet x width 12 feet

-

Use this image

You can download and use the high resolution image under a Creative Commons licence, for all non-commercial purposes, provided you attribute the copyright holder.

- Rights Holder: Stratfield Saye Preservation Trust

- License Type: Creative Commons

Find it here

This object is in the collection of Stratfield Saye