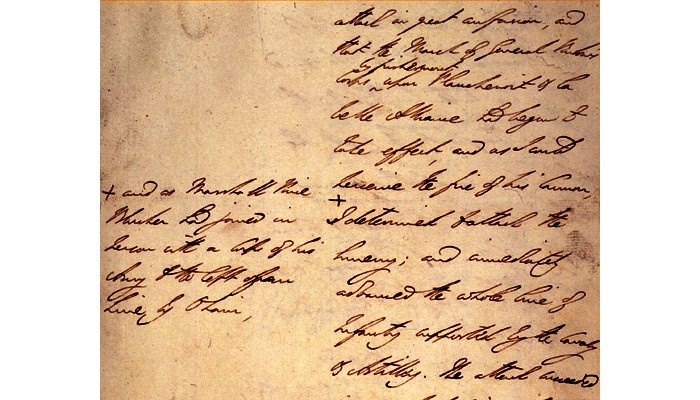

Waterloo Dispatch

This is a page from the Waterloo Dispatch, the document written by the Duke of Wellington the night after the Battle of Waterloo, on 19 June 1815, describing the Allied victory over the French.

Read the full text of the Waterloo Dispatch.

Listen to the actor Hugh Grant reading the Waterloo Dispatch.

It was dark when Wellington arrived back at the inn that served as his headquarters at Waterloo. He went straight to see his aide-de-camp, Colonel Alexander Gordon, who lay dying on Wellington’s own camp-bed, and then lay down to sleep.

A few hours later, Dr John Hume tapped on Wellington’s door, entered, shook the duke’s hand and told him of Gordon’s death at 3.30 that morning, as well as that of many other officers. Brushing his tears aside, Wellington said “Well, thank God, I don’t know what it is to lose a battle; but certainly nothing can be more painful than to gain one with the loss of so many of one’s friends.” With that he sat down to write his official dispatch to Earl Bathurst, Principal Secretary of State for the War Department in London.

He headed his first dispatch, ‘Waterloo 19th June 1815’, with the name of his own headquarters. As a result the battle was written into history by this name. He continued his account, beginning with the French concentration between 10 and 14 June and the attack on the Prussians along the Belgian border on 15 June. He explained that he did not hear of these events until the evening of that day whereupon he ordered his troops to march forward now he had intelligence that Napoleon was moving towards Brussels via Charleroi.

He described the actions at Quatre Bras on 16 June, followed by the main engagement at Waterloo two days later, and finally the defeat and pursuit of the French Army. He concluded with reference to the death of Sir Thomas Picton and also mentioned a number of senior officers ‘for his Royal Highness’s approbation.’

The dispatch was ready by midday and was carried to England, along with two captured French eagles, by the Honourable Henry Percy, another of Wellington’s aide-de-camps. Arriving at Broadstairs around 3pm on 21 June, he reached London around 10pm and delivered the news, together with the eagles, to the Prince Regent, who was dining at a house in St. James Square. An exhausted Percy could then retire to his family home at Portman Square.

The dispatch would later prove controversial because it failed to mention the commanders and formations that were subsequently considered more deserving of recognition than those actually picked out for commendation by Wellington. Perhaps the most honest account of the battle can be summarised by a British soldier on the morning after Waterloo: “I’ll be hanged if I know anything about the matter, for I was all day trodden in the mud and ridden over by every scoundrel who had a horse.”

-

Curatorial info

- Originating Museum: The British Library

- Accession Number: Add. 69850, f.10v

- Production Date: 19 June 1815

- Creator: Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington

- Material: Canvas, ink

- Creation Place: Waterloo

-

Use this image

You can download and use the high resolution image for use in a non-profit environment such as a school or college, but please take note of the license type and rights holder information below

- Rights Holder: Copyright British Library

- License Type: All Rights Reserved

Find it here

This object is in the collection of British Library