Passport Signed by the Duke of Wellington

Theme: Social and cultural revolution, People in motion: exiles and opportunities

Travelling in Europe was very popular among the British nobility, gentry, and professionals of the 1700s and 1800s. It became traditional for upper class men and women to embark on a lengthy ‘Grand Tour’ of Europe, where they would experience the languages and history of the continent while showing off their own status and wealth. It was also popular with British artists, writers and thinkers of the time, keen to broaden their experience and exchange ideas – particularly with their counterparts and the new celebrities and centres thrown up by the upheavals of revolution.

At this time, passports were not strictly required for travel from Britain to France – Britain had no restrictions on who could enter or leave the country, but travelling in Europe without papers could be looked upon with suspicion. From 1794, passports began to be issued by the Principal Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (who we would now call the Foreign Secretary). Previously all passports would have been issued and signed by the King or Queen.

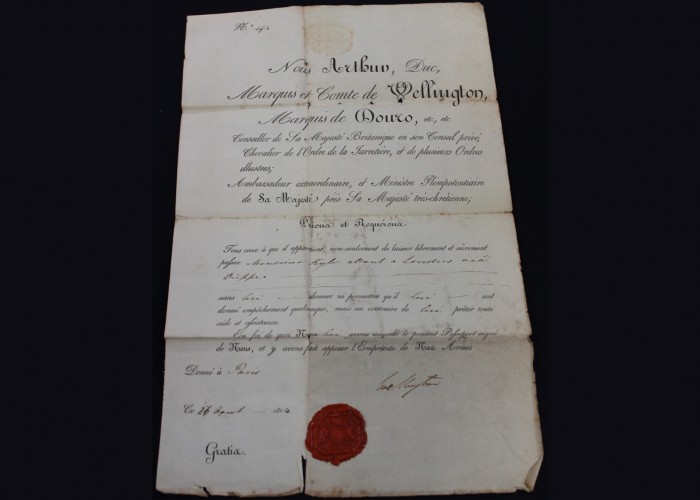

This is a passport, signed by the Duke of Wellington, authorising the bearer to travel between Britain and France. This passport is not only proof of the bearers’ authenticity, but also a guarantee of safe conduct. Personally signed by the Duke of Wellington, it shows that the full weight of the British government stood behind the holder of the passport.

It was issued on 26 August 1814, just under a year before the Battle of Waterloo, when the Duke was the British ambassador to Paris, and seeking to resolve diplomatic, constitutional, and economic relations. After Napoleon’s first abdication in April 1814, there was a temporary boom in travel to continental Europe after the long war and blockades. This ended abruptly when Napoleon returned from exile and marched into Paris in May 1815.

Did you know..?

Until 1778 British passports were written in English and Latin. After this date they were issued in French (as with this one) which was the language of diplomacy at the time, until 1858, when the passport first became a British identity document.

Sources & acknowledgements

This object description and its related educational resources were researched and written by our team of historians and education specialists. For further information see the item’s home museum, gallery or archive, listed above.

-

Did you know..?

Until 1778 British passports were written in English and Latin. After this date they were issued in French (as with this one) which was the language of diplomacy at the time, until 1858, when the passport first became a British identity document.

-

Education overview

You can access a range of teachers resources related to this object and more on our education page.

Please also see our glossary of terms for more detailed explanations of the terms used.

-

Curatorial info

- Originating Museum: Private collection

- Production Date: 26 August 1814

- Material: Ink, paper

- Size: 415 x 265 mm

-

Use this image

You can download and use the high resolution image for use in a non-profit environment such as a school or college, but please take note of the license type and rights holder information below

- Rights Holder: Copyright Alexander Rich.

- License Type: All Rights Reserved

Private Collection

Some objects - such as this one - are owned by private collectors. Waterloo 200 cannot give information on the ownership or location of these items.