Interview with Bonaparte at St Helena

This document is an account of a meeting in 1817 between Captain Basil Hall of the Royal Navy and Napoleon Bonaparte. Bonaparte was exiled following his defeat at Waterloo to the South Atlantic island of St Helena. The former French Emperor is described as having “a fervor and an anxiety to be informed [about the world outside his prison] which I have never met in any other person.”

Captain Hall, born in Edinburgh, had joined the Royal Navy in 1802 and was subsequently promoted to captain. Hall served on a number of navy ships during the Napoleonic Wars, including HMS Endymion. Aboard the HMS Endymion he saw the fatally injured Sir John Moore being evacuated after the Battle of Corunna in 1809.

On the same ship he met William Howe De Lancey, who married Hall’s sister Magdalene in April 1815. Within three months De Lancey was mortally wounded by a cannonball at Waterloo. His new wife nursed him for six days until his death. She later wrote a notable account of the experience, ‘A Week at Waterloo’.

The death of his brother-in-law was not Hall’s only connection to Napoleon. His father Sir James Hall had attended the French military college at Brienne in the 1780s, crossing paths with Bonaparte who was then an officer cadet in the pre-revolutionary French Army. It was this association that was to gain Hall his audience with the deposed Emperor.

Hall came to St Helena aboard HMS Lyra, which was transporting Lord Amherst, a British ambassador, back to the UK. The ship stopped at St Helena en route. In this account of the visit, Hall recounts his efforts to secure an audience with Bonaparte. His initial approach, via the island’s Governor (Sir Hudson Lowe) was rebuffed and an attempt to doorstop the Emperor also failed. It was only as a result of a conversation with Bonaparte’s doctor in which Hall mentioned his father’s attendance at the same college as Bonaparte that a meeting was arranged.

Hall actually met with the Emperor for around 20 minutes in the afternoon of 13 August 1817. During their conversation Bonaparte claimed to have remembered Hall’s father from his time at Brienne, and sought details about Hall’s voyages of exploration in the East, particularly the island of Loo-Choo. (Today known as the Ryukyu Islands) Hall recorded that he left with a positive impression of Bonaparte, but revealed at the end of his note that his father, Sir James, had no memory of Bonaparte from his college days, implying that the Emperor had not left a lasting impression. His notes can be found here.

Read a transcript of the whole account:

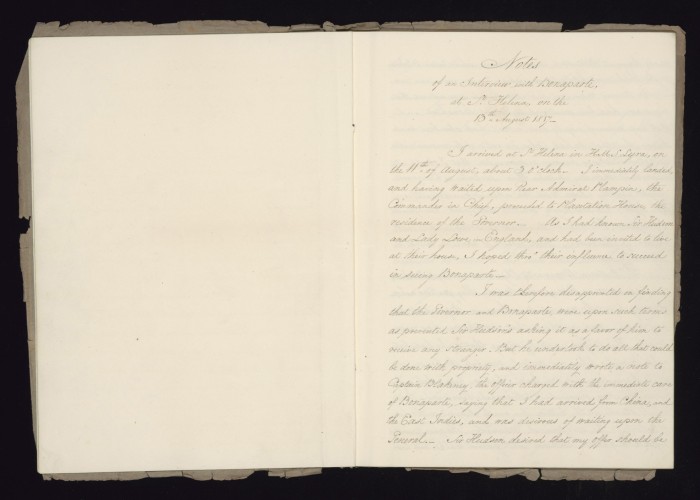

Notes of an interview with Bonaparte, at St Helena, on the 13th August 1817

I arrived at St Helena in HMS Lyra, on the 11th of August, about 3 o’clock. I immediately landed and having waited upon Rear Admiral Plampin, the Commander in Chief, proceeded to Plantation House, the residence of the Governor. As I had known Sir Hudson and Lady Lowe in England, and had been invited to live at their house, I hoped thro’ their influence to succeed in seeing Bonaparte.

I was therefore disappointed on finding that the Governor and Bonaparte were upon such terms as prevented Sir Hudson’s asking it as a favour of him to receive any stranger. But he undertook to do all that could be done with propriety, and immediately wrote a note to Captain Blakeney, the officer charged with the immediate care of Bonaparte, saying that I had arrived from China and the East Indies, and was desirous of waiting upon the General. Sir Hudson desired that my offer should be made known to Bonaparte in any manner which Captain Blakeney might think likely to succeed.

An answer was sent next morning to acquaint us, that my name had been mentioned to General Bonaparte, and that my desire of paying him a visit had also been made known, but that he had taken no notice of the communication. Captain Blakeney however recommended that I should visit Longwood that day, between three and four, as Bonaparte might possibly choose to see me when I was actually on the spot. I accordingly went to Longwood, accompanied by Captain Harvey of the Madras army, and Lieutenant Clifford of the Navy, both guests of mine on the Lyra.

Dr D’elleara, Bonaparte’s physician and Captain Blakeney received us near Bonaparte’s house. They gave us no hopes of seeing him – he was not in a humour, they said to see any body – and in short, that our chance was very small. They teased us too by saying that as he had but a few minutes before our arrival gone into the house, we might have seen him at least, had we been a little earlier.

We now repaired to Marshal Bertrand’s house, which stands at the bottom of a general slope, on the top of which is the residence of Bonaparte. They are separated by a neat garden, laid out with gravel walks, and low hedges, and here and there a tree. With the exception of this spot, and some small patches near the other houses, the surrounding scenery is bleak and desolate.

We found the Countess Bertrand, sitting in the midst of her family, in a small low uncomfortable room which was crowded with sofas and beds, cradles chairs, so implying that the apartment was used both as a bedroom and a parlour. The Countess had her head wrapped in a flannel, on account of a toothache. The fire scarcely heated the room, and the day being cold and rainy, the poor Lady looked very miserable. Every thing about her in short wore an air of privation and discomfort, strongly contrasted no doubt to her with what she must have been accustomed to in her past life. She herself however seemed less sensible to what we considered the misery of her situation, than we were. Her beautiful little children played about her all the time we were there with an artless unconscious gaiety not a little affecting. Her appearance and manner were very much in her favour. She is really a fine looking person, and though carelessly dressed was quite lady–like in her appearance. She conversed with us in perfectly good English with great cheerfulness, but not levity, and principally about her own situation, to which subject she was led by our remarks and questions. She took the first opportunity of turning the discourse to our present object, namely to get a sight of the Emperor, as she invariably called him.

She seemed to take an immediate and strong interest in our cause, perhaps from seeing our uncommon earnestness and anxiety upon the subject. So earnest indeed was she that one might have thought she herself was of the party who had never before seen Bonaparte.

If the Countess Bertrand rose in our opinion by her appearance and her manners, and the obliging interest which she took in our cause, her husband the Marshal did not by his appearance or behaviour sustain the high opinion of him which we had been accustomed to hold.

From all that had been said about this Officer’s fidelity, and talents, added to the circumstances of his being a Marshal, and so long the Companion of Bonaparte, we had naturally acquired a habit of thinking him with much respect, and of forming an idea of his appearance suitable to the character of a man so singularly circumstanced.

So that we were somewhat disappointed on seeing a shabby looking, ill-dressed person – with a whining expression of countenance and a poverty of manner altogether extraordinary in one who had lived so much in society. He looked it is true as if he had been unwell and without detracting from his well earned reputation we may naturally suppose that he must have been in some degree subdued in spirit by witnessing the privations to which his wife and children have been exposed. I feel therefore that in describing him as he appeared to us, that I may perhaps by giving a wrong impression, be doing injustice to a man whose character ought not to be estimated from his looks at such a moment.

After sitting for about a quarter of an hour in close conversation about the great object of our visit, Bertrand appeared to catch some portion of the interest which we felt, and in which his wife so strongly participated. He rose and said he would wait upon the Emperor in order to communicate our wishes and then return to inform what his Majesty might be pleased to order.

From Bertrand’s manner we feared that we should not see Bonaparte, but as he did not speak confidently we were left in a stage of the most anxious suspense. The Countess continued talking in the most lively style, and we also tried to be gay, but our anxiety was so great that upon the slightest noise at the door, we all started up in expectation of a summons. Meanwhile the Countess took as much pains to console and reassure us, as if we had all been on the brink of some great calamity.

It was an hour at least after Bertrand’s quitting the room before we heard what was the issue of his interview with Bonaparte, and then instead of coming himself as he had promised us he would do, he sent a footman, who walked unceremoniously into the room, and told us that his Majesty, on coming in from his walk, had thrown off his coat and that he could not receive any visitors!

There then was the end of all our hopes! and we rose to go away with a mingled feeling of disappointment at losing an enjoyment which we had flattered ourselves was within our reach. Anger at the ex Emperor for his cavalier treatment of us – and not a little contempt of ourselves for having given the whole transaction such undue importance.

We had mounted our horses and rode away a quarter of a mile, when it occurred to our recollection that as Dr Delleara was said to possess great influence over Bonaparte, or at all events had considerable knowledge of his peculiarities from being so constantly in his company it might be as well to consult with him in order to discover whether or not it were still possible to contrive an interview. We accordingly turned back, and got into conversation with Dr. Delleara, who gave us little hopes until I chanced to mention that my father Sir James Hall had been at Brienne during the time Bonaparte was there. “Indeed” said the Doctor “I wish we had known this before. I have little doubt that General Bonaparte would have seen you had he been aware of this circumstance. He is already somewhat interested about your recent voyage to Loochoo, but having said that he would not see you, something of this kind was wanting in addition as an excuse. Perhaps it may not yet be too late, but for this night you must necessarily give it up. Should Bonaparte when I tell him of what you have just stated, express a wish to see you, I will immediately inform Sir Hudson Lowe of it by telegraph”.

With this slender hope we left Longwood. My companions went to James’s Town and I returned to Planation House for the night.

13th August – As Dr Delleara had promised to let me know in the course of this morning what Bonaparte’s answer was, I remained ready to set out at a moment’s warning. The day passed however without any signal being made that we knew of, till three o’clock. The signal man at Plantation House gate then came to the house to report that a signal had been made from Longwood at one o’clock to the following effect.

“General Bonaparte wishes to see Captain Hall at two o’clock”. The signal man at the gate, supposing that I was in James’s Tiwn had forwarded the message there, instead of bringing it to the house. Owing to the weather being hazy is was two hours before the message could be transmitted back again from James’s Town to the Governor’s.

I lost no time in obeying the invitation, but galloped over the hills as fast as I could, being prompted to use all speed lest Bonaparte should think that I had intentionally kept him waiting. I found my companions waiting for me at the outer gate of Longwood. They had been aware of the telegraph message much earlier that I was, and had proceeded instantly to meet me. The officer at the Gate however would not allow them to pass until I showed the passport from the Governor.

On reaching Longwood we were shown to Bertrand’s house, where we found the Countess Bertrand unaffectedly pleased at the prospect of our wishes being gratified. Bertrand said is was the Emperor’s desire that I should be admitted alone first, and that my two companions would be presented afterwards. I stated to Bertrand that as I spoke French badly, and with difficulty, I should prefer his being present to assist me if I should fail to make myself understood. I had heard so much of the embarrassment which some people had experienced on being admitted to Bonaparte’s presence that I thought it prudent not to rely upon the confidence which I felt that I should not be discomposed, except by want of a sufficient knowledge of French to make myself understood.

Bertrand went on before to mention to Bonaparte that we were in attendance. In about ten minutes a servant came to say the Emperor was ready to receive us. We were then shown to a small antechamber in Bonaparte’s House, where Bertrand met us.

On being ushered into the room, I observed Bonaparte standing before the fire. He was leaning his head on his hand, with his elbow resting on the mantle piece. He looked up and immediately advanced a pace towards me, returning my bow in a quick, careless manner. On my going close up to him he asked me in a hurried way “What is your name?” I answered “Hall”.

(It may be proper to mention in this place that although the conversation was carried on in French, I have given it here almost entirely in English. My reason for doing this rather than attempting to give what was said in the language in which it was spoken, is, that with the limited knowledge which I have of French, and the difficulty of catching Bonaparte’s peculiar modes of expression, I should probably have committed some faults in language which would have had the effect of throwing a doubt over the whole, whereas by giving a translation I can be quite sure of conveying the meaning of what was said with as much accuracy as possible, and this is all I pretend to have attempted.

I should have stated before, that the notes from whence this account is drawn up, were written immediately after the interview. I merely waited upon Sir Hudson Lowe to report what had passed, and then went on board the Lyra, where I wrote down all that I could recollect of the conversation, before I slept).

Upon telling him my name he said, “Ah Hall, I knew your Father at Brienne. He was then learning French and reading Mathematics. He was very fond of Mathematics and liked to converse on the subject. He did not mix much with the young men at the college; he lived principally with the priests, apart from us.

On his pausing, I said that I had frequently heard my Father mention the circumstance of his having been at Brienne, while he (Bonaparte) was at the Military College, but that he had no expectation of his being so long held in remembrance. I expressed some surprise at his recollecting any individual for so long a time, when his thoughts had been so much engaged with important affairs. “Oh it is not in the least extraordinary” said Bonaparte “because your Father was the first Englishman I ever saw, and I have recollected him on that account during all my life”. After a short pause he said with a good humoured expression of countenance, as if amused at the questions he was putting. “Did you ever hear your Father speak about me?”. I replied at once “Yes very often”. Upon which Bonaparte hastily demanded “What does he say of me?” accompanying the question with a keen humorous glance, and commanding look which seemed to signify that he expected an immediate, and an honest answer, and not any thing studied. Fortunately I recollected something complimentary which I had heard my father say of him; and I replied instantly by saying that I heard my Father speak with great admiration of the encouragement which he had always given to science while he was Emperor of the French.

He appeared gratified by this, and testified his satisfaction by laughing quite heartily, and making several half bows towards me as if to acknowledge that he felt honoured by such testimony in his favour.

“Well”, resumed Bonaparte, “did you ever hear your Father express any wish to see me”? I told him that I had often heard my Father say there was no person alive so well worth seeing, and that I had received my Father’s injunctions by all means to pay my respects to him should I touch at St Helena. “Very well”, retorted Bonaparte in a playful manner, “if he really wishes to see me why does he not come to St Helena for that purpose”?

This was said in a rather jocular manner, but as there was something interrogative in his tone I thought it was right to say that my Father’s situation prevented his going so far from home. Upon his asking me more particularly about my Father’s occupations, I told him that he was president of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

This furnished him with a new topic, and he continued for some minutes cross questioning me about the nature of the Edinburgh Royal Society. He wished to know whether the Presidency was for life, or was elective annually; desired me to describe in what manner subjects were brought before the society, and how they were discussed. On his hearing that there were several hundred members he drew back with a look of surprise and exclaimed, “These cannot all be men of science. They cannot all attend the meetings, and some of course merely go there from their love of science”.

After talking for some time on this subject he returned again to my Father saying, “I am certain that your Father must be nine or ten years older than I am – at least nine years – I think ten – is it not so”? I replied that I believed he was correct. Upon which he turned nearly half round on his heel, and laughing very heartily nodded his head as if to imply that he had considerably the advantage of my Father in being so many years his junior.

He next asked how many children my Father had? I said, “Nine alive”. “Ah c’est beaucoup” said Bonaparte with an air of affected gravity accompanied by a formal sort of bow, as if he felt desirous of making up for the slighting manner in which he had just been treating my Father on the score of age.

His next question was, “Are you married?”, and on my stating that I was not, he asked in a quick impatient way, “Why don’t you marry?”. I hesitated a moment, but seeing that he was waiting for my answer, I said that I had not money enough to enable me to marry. “Ah ha” exclaimed Bonaparte several times “faute d’argent, faute d’argent”, laughing heartily at the same time, and nodding his head as if he deemed the reason satisfactory enough.

He next asked how long I had been in France, and upon hearing that I had never been there, he desired to know where I had learned French. When I told him I had picked up the little I knew from Prisoners of War on board various ships, he asked “Were you a prisoner amongst Frenchmen? Or were Frenchmen your prisoners?” On my explaining that it was the latter, he nodded several times.

Bonaparte now began questioning me about our late voyage of discovery, of which he had heard nothing from any of the gentlemen of the [HMS] Alceste who had preceded me. This was very fortunate for me, because the topic was quite new to him. It accordingly interested him highly. Bonaparte had been always supposed to have a strong taste for every thing oriental, and for whatever related to voyages of discovery in particular. I can fully believe that this is correct, for he appeared deeply interested in by the account which I gave him of what we had seen, and he carried on his enquiries with a fervour and an anxiety to be informed which I have never seen in any other person.

It would be in the highest degree satisfactory to be able to give his questions in the order and in the very words they were put, but this is unfortunately not in my power. They were very numerous and sagacious, not thrown out at random, but ingeniously connected with one another, so as to make every thing assist in forming a clear comprehension of the subject. I felt that there was no escaping his scrutiny, and such was the rapidity and precision with which he apprehended the subject, that I felt at times as if he were as well or better informed upon it than I was myself, and that he was interrogating me with a view to discover my veracity and powers of description.

He began by fixing the geographical position of Loochoo in his mind, by asking how far it was from China and in what direction. Then from [K]orea, next from Japan and lastly from the Philippines Islands. When I had answered these questions as accurately as I could, he looked quite satisfied that he knew whereabouts it was, and all that he said afterwards showed that his local geographical knowledge was very extensive and precise.

Having settled where Loochoo was, he went on to enquire about the people, making some amusing comments about their peculiarities. On telling him that they had no arms, he said, “No arms, you mean no cannon but they have muskets?” I said not only have they no cannon, they have no swords nor spears. “Ne Poignards” asked he. No, I replied we never saw any kind of warlike weapons. “Mais” said Bonaparte in a loud voice and with a manner more vehement and impatient than I had seen before, ‘Mais sans armes comment se bat on”, seemingly provoked that these simple people had no means of breaking that tranquillity and peace of which as far as we know they are the exclusive possessors.

I stated to him that they had no wars, upon which he shook his head, as if the supposition were monstrous and unnatural.

When told that the people of Loochoo had no money, he begged to question the fact. I said we had seen no money and that the people placed no value upon our gold and silver coins. He paused and looking thoughtful repeated to himself several times, “They do not know the use of money” and then he asked how we contrived to pay for the provisions which they gave us. He was apparently much struck with the liberality of these people, who supplied us with all kinds of stock, and to so great an extent without taking any payment. He made me describe every thing we received from the natives, as well as what we had given them by way of presents.

I held Mr Havell’s drawings in my hand, of the scenery and costume of [K]orea and Loochoo (since published), he asked to look at them, and taking the sketch of the [K]orean chief in is hand, he ran his eye over the different parts, repeating to himself as he examined it, “An old man, with a long white beard, ha, a large black hat, pipe, chinese mat, chinese dress, a man writing, ha”. The nodding his head and smiling he said, “C’est bon ca”, and looked at the rest. He asked what their dresses were made of and from whence they got their cotton and silks, and of what degree of finesses their manufacture was. He was no less minute with respect to their sandals, their fans, their pipes, and in short not the smallest circumstances in any of these pictures escaped his observation.

When he saw the drawing of Sulphur Island, he laughed, and holding it up exclaimed, “Cest St Helena mime!”

He next interrogated me about their agricultural operations, how they cultivated the ground, what their principal crop was. Whether they used horses or bullocks to draw their ploughs. Then about the appearance of the Country, the climate, and the construction of their houses. He enquired minutely how the lower classes were dressed, and what their food was, and how they were treated. Asked a great number of questions about the boats of the Island and the manner of fishing practised by the people of Loochoo. He appeared highly amused by the pertinacity with which the women were kept out of our sight. He was particular in his enquiries respecting their implements of husbandry, and their different working tools, and thence to their manufacture of iron, of salt and of wine. He then asked about their Religions, wished to know if we had seen their idols, and seemed particularly struck with the account which I gave him of the low state of the Priesthood.

He was in high spirits while putting these questions and carried on in his enquiry with so much cheerfulness, not to say familiarity, that I was more than once thrown completely off my guard, and caught myself unconsciously addressing him with the freedom and confidence of an equal. When I checked myself upon these occasions and became more formal and respectful, he encouraged me to go on with so much real cheerfulness, that I soon felt myself quite at ease in his presence.

On his desiring me to tell him what these Loochoo people knew of other countries, I said they know a little of China, and a little of Japan. “But of Europe?” said Bonaparte, I told them that they had never heard of France, nor of England, “nor” continued I emboldened by his extraordinary familiarity and good humour, “have they even heard of you!” Bonaparte appeared highly amused by this piece of impudence. The implied compliment seemed to flatter his vanity more than the impertinence of the remark hurt his dignity, for he laughed heartily for a minute or two at what I had said.

He continued his enquiries respecting our voyage for some time, and it is worthy of remark that in preparing the notes made during this voyage for publication, I have scarcely discovered a single topic on which Bonaparte did not put some questions. He spoke deliberately and distinctly, and waited with the upmost patience and attention for the answers. His pronunciation was so clear that I never lost a word which he spoke. On two occasions only I did not understand the meaning of some words which he made use of, but upon his repeating to Bertrand what he had said to me, in order that it might be interpreted, I caught his meaning before Bertrand had time to give it in English.

He adverted in a careless way to our news from India, and spoke of the Mahratta War as a circumstance of no importance.

In speaking again about my Father, to which subject he recurred very often, he asked what were the branches of science to which he had paid most attention, and what books he had written. When I had answered these questions, he begged to know whether my Father was one of the Edinburgh Reviewers. I replied that I believed not, but that his works had been criticised by the reviewers, upon which he laughed and turned round on his heel towards Bertrand, evidently amused at the idea of anyone’s being under the hands of these Gentlemen.

He asked what was the size of the Lyra, and said in a decided way “You will reach England in thirty five days” (we were sixty two days on the passage). After which observation he paused for some minutes, and then making me a quick bow said, “Allons Monsieur, bon voyage”. To which I replied by as a bow and retied, after having been about twenty-five minutes in his presence.

Bonaparte struck me as being different in appearance from any of the representations of him which I had at that time seen[1]. His face was larger and more square than it is given in the pictures and busts, and the breadth of his body, particularly across the shoulders, is considerably greater than I had expected. From the accounts we had received if his corpulency we had been prepared to meet a very fat man, but although he is certainly large in the body, it would not have occurred to me to describe him as being corpulent. His flesh looked firm and he was what is termed well set. His legs in particular were well made, and rather small. His complexion was quite pale, approaching to white. There was not the least appearance of a wrinkle either on his brow or at the corners of his eye. Were it not for an occasional lighting up of the eyes, and a sort of determined commanding glance, which as it were into one’s most hidden thoughts, I should have been disposed to describe his look as being placid or gentle, and at all times lively, but never stern.

Nor was there the slightest trace of care visible in his face or in his manner; on the contrary his whole deportment, conversation and expression of countenance indicated a mind perfectly at ease.

I was particularly stuck with the extraordinary play of his upper lip. But it is very difficult to describe. The more so to me as I did not seem him actually under the influence of any strong emotion, and what I did observe therefore, served not so much to show the expression itself, as to suggest to the imagination what possibly might be the powerful effect of his eye and lip in giving character to his expression when he is strongly moved.

His air was that of a character quite unsubdued and far above being affected by the ordinary accidents of life. This tranquillity was probably assumed, but if so he certainly played his part most skilfully, for I could discover nothing during the interview which betrayed the least ill humour, or impatience at his situation. Indeed he made no allusion to it whatever, directly or indirectly.

His manners were so good that from the first moment of the interview to the last, I felt myself not only at ease in his company, but every now and then I thought I was speaking to him in too familiar a tone. I wished of course to show him all sorts of respect and attention, but his cheerful and encouraging manner threw me repeatedly off my guard.

I was fortunate in being able to furnish him with two new topics. The circumstances of his recollecting my father and our voyage of discovery.

When speaking upon the first of these topics, he was particularly animated and seemed unaffectedly delighted by hearing accounts of an old school fellow. All this is so natural that there does not seem much difficulty in believing him sincere. As most people remember their boyish days, if not with pleasure, at least with interest, there is no reason why Bonaparte should not look back across the turbulent field of his past life and view with complacency from his present retied station, the gay and innocent scenes of his youth.

Amidst the stormy emotions of his ambitious career one would naturally have supposed that such calm recollections as these would have been swept away, and that they had now returned upon him with greater force from having been so long unheeded. But the fact is otherwise, for in the very midst of his most arduous military operations, where pressed on all hands by the Allies, at a moment when of all others he might have been supposed most occupied with present objects he had leisure to enquire in the most cool and deliberate way about his old school fellows and friends, whom he had no seen for upwards of thirty years. This occurred when he was engaged with Blucher near Brienne in 1814. He had never visited the spot since he first left the college in 1782 or 3, and upon returning to it under circumstances as different as can well be imagined, he caused enquiries to be made for people who had been at the college during the time of his residence there. The old Priest who had actually been over Bonaparte was still alive, and was brought to him. He detained him for a long time, asking about all the Scholars by name, and making the old man tell him the history of the different priests, servants and every body connected with the Institution. He even asked what become of certain Houses which he missed and in short seemed as well informed upon every thing relating to the spot as the old man who had never quitted it.

I have the above anecdote from an extremely intelligent officer who was at that time one of Bonparte’s suite. The same Gentlemen tells me that Bonaparte was at all times interested in every thing that related to Brienne and that whenever he heard of any officer who had been educated there at the same time with himself, he sent for him, and if he were deserving of promotion, immediately advanced him.

My Father does not remember Bonaparte. That he was there at the same time with him is certain, but most unfortunately his journal which had been kept day by day for some years before, stops a few weeks before he went to Brienne. My Father was not actually a student at the Military College. He was at Brienne on a visit to the late Mr W. Hamilton, who lived at the Chateau de Brienne.

My Father has an obscure recollection of some boy at the Military College having blown up one of the garden walls with gunpowder, but he does not recollect his name. The circumstance was brought to his recollection, and connected itself with Bonaparte at the time of his first rising into the notice as a great military character. Whether or not he was the mischievous youth who demolished the wall is uncertain, but it would be an amusing question to put to Bonaparte himself.

My two companions were received together after I left the room. He put a few common place questions, and dismissed them, he was no less polite however to them, than he had been to me. Observing crape on Captain Harvey’s arm, he begged to know for whom he was in mourning and on learning that it was for his father, he appeared sorry, or at all events testified by his manner that degree of respect for the feelings of his guest, which a well bred person is at all times disposed to pay, particularly to a person in distress.

Basil Hall

Captain RN.

[1] Since writing the above I have seen an excellent picture of Bonaparte, in the profession of a Mr Richard Power of Dublin. It was painted in 1805, by Girard and given to the City of Rome in 1810. Mr Power bought it at Rome in 1817. This picture has much more of Bonaparte’s expression of countenance than any I have seen. It represents him of course smaller than he is now, but the face is extremely like, and is remarkable for conveying the placidity and sweetness of expression which is at times so very striking in his countenance. The Princess Borghese sent to Mr Power to say that she considered this picture as being the best of any that was ever painted of her Brother.

-

Curatorial info

- Originating Museum: National Army Museum

- Accession Number: NAM. 1968-07-391

- Production Date: 1817

- Creator: Captain Basil Hall

- Material: Ink on paper

-

Use this image

You can download and use the high resolution image for use in a non-profit environment such as a school or college, but please take note of the license type and rights holder information below

- Rights Holder: Copyright National Army Museum.

- License Type: Creative Commons

Find it here

This object is in the collection of National Army Museum