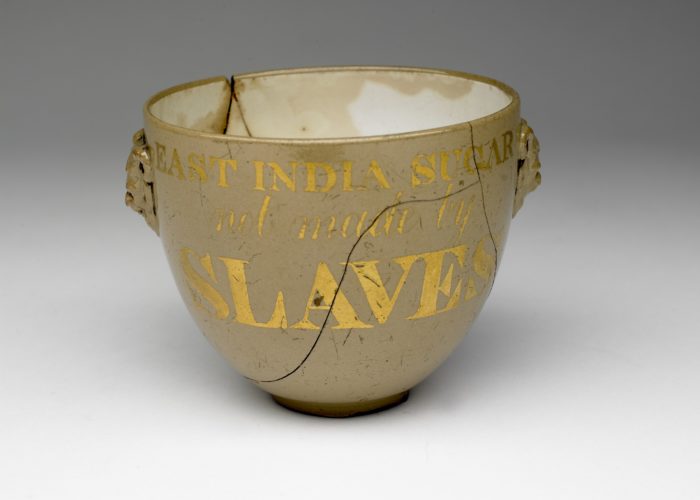

Anti-slavery sugar bowl

Theme: Revolutionary ideas, Haitian revolution (1791 - 1804), Challenging law and order: British riots and reforms, Social and cultural revolution, Challenging slavery: abolition and opposition, People in motion: exiles and opportunities

Between the 1500s and early 1800s, millions of Africans were kidnapped, sold and transported to the Americas to work as slaves in unimaginably cruel conditions on hugely profitable plantations. These plantations were largely owned by Europeans and Euro-Americans. Britain grew rich on the profits from this transatlantic slave trade, reinvesting the profits in other economic sectors. Only in the late eighteenth century did public opinion slowly begin to turn against the trade in Africans, and campaigners for abolition used every way they could to bring the issue to people’s attention in Europe.

This economic campaign gathered pace and became one of the first national boycotts in British history.

One of the ways British people were encouraged to challenge slavery, was to stop buying sugar – one of the most profitable products of the Caribbean plantations. Many of those behind this type of protest were women, often in influential households. Although without the vote, they saw that by boycotting the sale of West Indian sugar they could contribute significantly to the abolitionist movement, learning from boycott measures used in political revolutions. When the government failed to abolish slavery in 1791, this economic campaign gathered pace and became one of the first national boycotts in British history. The British trade in people was outlawed by the government in 1807 and British slavery finally abolished in 1833.

The maker of this bowl is unknown. One of the most famous producers of ceramics at the time was the potter and industrialist Josiah Wedgewood. Like other reformer-entrepreneurs, including many Quakers and dissenters, he was an active campaigner for the abolition of slavery, producing medallions, cups, saucers and other household pieces that raised awareness and helped mobilise the campaign.

The message on this bowl is that people should buy ‘East Indian sugar not made by slaves’.

Did you know?

Even in cities that were heavily reliant on the slave trade, like Manchester, 20% of the population signed petitions supporting abolition. Feeling was so strong that even pro-slavery politicians recognised the need to pay attention. Like the FairTrade movement today it demonstrated the power of public opinion to change even the most entrenched systems and beliefs, even when it may increase economic cost.

Use our Classroom resources to investigate this object and the theme of Abolition further.

Highlights:

Sources & acknowledgements

This object description and its related educational resources were researched and written by our team of historians and education specialists. For further information see the item’s home museum, gallery or archive, listed above.

- Enquiry Questions

-

Education overview

You can access a range of teachers resources related to this object and more on our education page.

Please also see our glossary of terms for more detailed explanations of the terms used.

-

Curatorial info

- Originating Museum: Hull Museums

- Production Date: late 1700s-early 1800s

- Original record

-

Use this image

- Rights Holder: © Wilberforce House, Hull City Museums and Art Galleries, UK/Bridgeman Images.

- License Type: All Rights Reserved

Find it here

This object is in the collection of Wilberforce House Museum