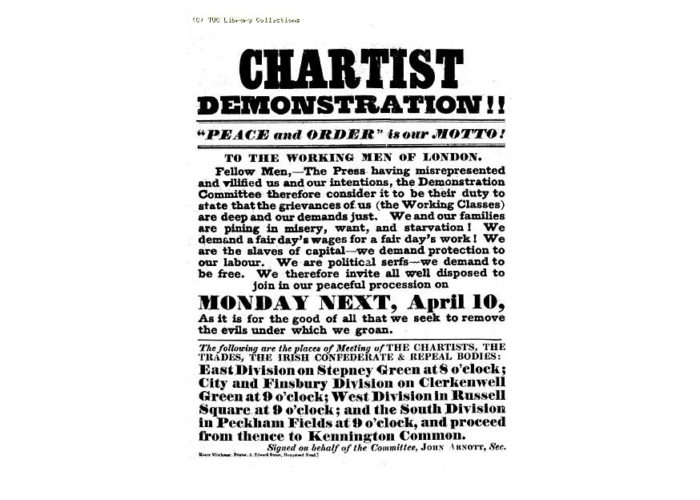

Poster advertising the Chartists’ Demonstration on Kennington Common, 1848

Theme: Revolutionary ideas, Challenging law and order: British riots and reforms, Economic and technological revolution, Printing revolution, British politics in the Age of Revolution, Redesigning Europe

The Chartists were members of a national and generally peaceful protest movement who campaigned between 1838 and 1857 for political reform and representation of working class people. It was the first British mass movement to be driven by the working classes. The development of the industrial printing press helped spread the word and gather support for peaceful protests. The Chartists’ ‘demands’ still underpin British democracy today.

In 1837, a group of working men led by William Lovett (1800 – 1877) came together to campaign for political reform. In 1838 Lovett published the People’s Charter, calling for six key reforms that would give ordinary working men a voice and make the political system more democratic. These were:

- All men over the age of 21 to have the vote (universal male suffrage)

- Voting should take place by secret ballot (to make sure individual votes could not be influenced by others)

- Parliamentary elections every year, not once every five years (to remove corrupt governments)

- Constituencies should be of equal size

- Members of Parliament should be paid

- Members of Parliament should not have to own property

The Chartists, as they became known, chose to fight for their cause peacefully. The drive to spread the word, gather support and mount peaceful protests was led by Feargus O’Connor (c.1796 – 1855). The development of the ‘industrial’, steam-powered printing press meant pamphlets and posters could be mass-produced quickly and cheaply, and the movement soon gathered support. It also made its voice heard through periodicals, poems, public gatherings and its own newspaper – The Northern Star. In 1839 a petition was presented to the House of Commons with over 1.25 million signatures, only to be rejected.

Unperturbed, the movement submitted two further petitions. The Chartist’s second petition, presented in 1842, contained a staggering 3.3 million signatures. After debating it for two days, Parliament once again rejected the People’s Charter. In 1848, posters like this one advertised the march on Parliament to deliver a third charter. The plan was to gather on Kennington Common, but fear, sparked by the violence of the February Revolution across the Channel in Paris, spooked the British government, who feared a violent protest. Taking no chances, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were evacuated to the Isle of Wight and troops stationed on London’s Bridges. O’Connor had no choice but to abandon the march. He later delivered the petition to the House of Commons, only for the Charter to be rejected again.

Despite attempts to keep the movement alive, it began to dwindle as a driving force for reform. However, its legacy was strong and over the coming years reform acts were passed which responded to the cause. By 1918, five of the Chartists’ six proposed reforms had been made. Only the demand for annual parliamentary elections remains unfulfilled.

Did you know..?

When the Chartist’s second petition was delivered to the Houses of Parliament, its 3.3 million signatures made it too large to fit through the doors and it had to be disassembled.

Sources & acknowledgements

This object description and its related educational resources were researched and written by our team of historians and education specialists. For further information see the item’s home museum, gallery or archive, listed above.

- Enquiry Questions

-

Did you know..?

When the Chartist’s second petition was delivered to the Houses of Parliament, its 3.3 million signatures made it too large to fit through the doors and it had to be disassembled.

-

Education overview

You can access a range of teachers resources related to this object and more on our education page.

Please also see our glossary of terms for more detailed explanations of the terms used.

-

Curatorial info

- Originating Museum: Museum TUC Library Collections, London Metropolitan University

- Production Date: 1848

- Original record

-

Use this image

Image courtesy of the TUC Library Collections at London Metropolitan University

- Rights Holder: TUC Library Collections, part of London Metropolitan University's Special Collections

- License Type: All Rights Reserved

Find it here

This object is in the collection of TUC Library Collections